Policy Recommendations

- The current employment and income inequalities will lead to future gender gap in pensions (GGP) unless significant income improvements for women are enforced.

- Pension policy as well as gender equality measures have to be long-term in nature and formulated well beyond an election period. Short-term and ad hoc reforms reduce the confidence in the pension system, make it less transparent and less reliable.

- As gainful employment is increasingly losing its function of securing the livelihood (atypical work), new elements in the pension system have to guarantee old-age income by introducing a gender-gap-factor to increase pension entitlements, re-evaluation of gainful employment and care work.

Abstract

The measures many governments have taken 2020 in order to contain the coronavirus pandemic dominates the economic policy. Nevertheless, there are long-term conditions and structures which are little, if any, changed by the short-term economic business cycle. The economic inequality between women and men in the current economic system is one of these structures. The extent of the damage caused by the crisis cannot yet be assessed. What is certain, however, is that the economic situation of women and their financial independence is under further pressure as a result of developments in 2020: The rising unemployment and the increasing need to perform more (low and unpaid) care work will imply negative consequences for the old-age security of women.

Even now, within the European Union women have on average a 30% lower retirement income than men. This gap is known as the gender gap in pensions. Country differences range from 43.1% (Luxembourg) to 1.1% (Estonia). Austria has (38.7%) the fourth highest gender gap in pensions within the European Union. Despite an above-average economic performance per inhabitant and an above-average employment rate for women, Austria occupies a negative top position in this respect. Using recent data of the 2017 pension access cohort, the gap in old-age pensions in the statutory pension scheme (first pillar) is even higher and reaches 42.3%. The different levels of earned income over the course of working life explain 55% of the gap. The lower number of working years explains 41% of the gap. The different levels of partial insurance (unemployment and child care periods) explain about 4% of the gender gap in retirement.

****************************

The gender pension gap in Austria and Europe

Level and causes of the gender pension gap in Austria and Europe[1]

1. Lower female pensions worldwide

The fact is well known: “Women receive lower pensions than men worldwide”[2] (OECD 2019A, p. 45). The pension gap compares the retirement income of women with those of men[3]. It indcates the percentage of women’s disadvantage in pension income at a given point in time and shows the long-term consequences of the structural economic and social disadvantage of women compared to men[i]. The gap echoes effects of past labour market and income conditions which continues to exist in old age through institutional regulation. The indicator that processes cross-sectional information (pension level at a certain point in time) and longitudinal information (employment history) necessarily presents a certain picture and leaves other perspectives and questions open e.g. poverty risk of women in old age.

In the European Union 6.2% of female population age 65 to 74 have no pension entitlement at all.

In employment based old-age pension systems, low labour market participation of women is reflected in a lower share of retirement claims compared to men. Thus, not only the different pension levels, but also the fact whether women are entitled to pension payments at all, defines the economic situation in old age. In Denmark, the Netherlands and Sweden people of a certain age receive a universal pension benefit, so there are no differences in pension claims between men and women.

In the European Union 6.2% of female population age 65 to 74 have no pension entitlement at all[4]. In Denmark, the Netherlands and Sweden people of a certain age receive a universal pension benefit, so there are no differences in pension claims between men and women.

In countries with employment-based pension systems, however, the coverage effect between women and men differs markedly: in Austria[5] 18.4% of women aged 65 and over have no own pension entitlement. After taking survivors’ pensions and other regular old age income into account, the proportion of women with no pension entitlement is still 11.4% (men 0.6%). In Malta the coverage gap is 34%. Also, Spain (27%), Belgium (17%), Ireland (16%) and Greece (13%) are countries with a large group of women with no pension entitlements.

In Austria, however, it is not only the proportion of women without a pension entitlement that is above average in European comparison, but also the pension gap.

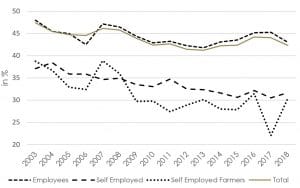

In Austria, however, it is not only the proportion of women without a pension entitlement that is above average in European comparison, but also the pension gap. The OECD data shows that the retirement income of women in Austria is on average 42% lower than that of men. According to EUROSTAT calculations, the gender gap in Austria is 38.7% in the over-65 age group. This picture is also confirmed when only one cohort is considered: In the statutory pension scheme newly retired women in 2018 reached an average pension payment of €1.133 gross per month, which is only 57.7% of men’s pensions. The gender gap in pensions of 42.3% among new retirees is even higher than in the population 65 and older. Since pensions and earned income are very unequally distributed and concentrated in the lower half of the distribution, the median pension income is lower than the average pension income. The gender gap of median pensions is therefore significantly higher and reaches 49.2%. Big differences can also be seen along the insurance groups, where the following applies: The lowest pensions are paid to self-employed persons in the agricultural sector, where the gender pension gap is 29%, while the gap is considerably larger in the salaried sector (Figure 1). Even taking the different life expectancy into account (average remaining life expectancy at the age of 65 differs by 5.1 years) the gap remains at a high level of 36.2%.

Figure 1: Old age pensions in Austria: Development of the Gender Gap in Pensions 2003-2018

Regardless of the calculated level of the gender gap in pensions, all existing empirical findings show a clear systematic and structural pension disadvantage for women.

Regardless of the calculated level of the gender gap in pensions, all existing empirical findings show a clear systematic and structural pension disadvantage for women. This gap is independent of the statistical sources used and also independent of the calculation methods used. The gap therefore exists not only in Austria, but in almost all countries.

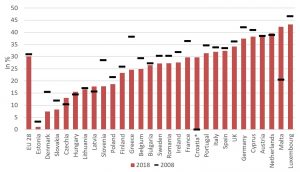

In the European Union, women in Luxembourg have the greatest disadvantages in terms of old-age income compared to men, with a gap of 43.3%. In Malta (42.3%), the Netherlands (39.6%) and Austria (38.7%) the gap is also clear above the European average of 30.1%. In nine EU member states the gap is above average, in the remaining 18 countries it is clearly below the European average. Only in Estonia there is no significant gap (Figure 2). The data show, that the gender gap in pensions are many times wider than the gender pay gap.

Figure 2: Gender pension gap in the European Union, 2008 and 2018

In Austria and Malta, the economic situation of women in old age is characterized by 2 negative factors: (1) An above-average proportion of women aged 65 and over with no pension entitlement and for those with pension entitlements (2) an above-average pension gap.

The four countries with the highest gap in 2018 have very different pension systems: In Luxembourg, Malta and Austria, the level of benefits in the mandatory system depends on the level and duration of contributions. Although the dual Dutch system guarantees a basic pension for all inhabitants, it cannot compensate the inequalities arising from the income-dependent pension, which is regulated by collective agreements. The main explanatory factors of the gender gap in the four mentioned countries are to be found in the labour market: The labour market is a system upstream of the old-age security system, the pension system depends upon the labour market. Thus, the pension system perpetuates and, in some cases, reinforces labour market inequalities. Conversely, the inequalities in economic security in old age must be combated with measures and reforms of the labour market as well as reforms in the pension system.

2. Causes of the pension gap in Austria

The extent of the economic disadvantage of women in old age can be reduced if both the influencing factors and their magnitude are known. The analysis of the 2017 pension cohort (statutory pension only) showed the following results for Austria:

- Half of the women have 12 contribution years less than men from active employment. This would result in a lower replacement rate by 21.3 percentage points.

- By taking into account the insurance periods for unemployment (linked to unemployment insurance benefits) and child rearing (maximum 4 years per child), the pension-relevant insurance periods increases especially of women. The gender gap in the replacement rate thus decreases from 21.3 to 13.6 percentage points.

- The main factor for the pension gap of women is the lower earned income during their working life. Over the entire working life, women’s income reaches on average only 60% of men’s income. Main reasons are the lower wages per hour and the higher part-time employment rate.

The main factor for the pension gap of women is the lower earned income during their working life.

From the above factors, the gender gap in pensions of the 2017 pension cohort was 48.1%. On average woman have €752 (gross) less than men per month. The lower level of earned income over the course of working life explain 55% of the difference. The lower incomes of women from low pay and part-time work lead to lower monthly gross pension of €413. The lower number of insurance years explains 41% of the gap, which corresponds to €306 per month. The different situation and level of partial insurance and contribution periods explain about 4% of the gender gap in pensions.

3. Perception of the pension gap by women in Austria

Women identified both the existing gender-specific income gap and the gendered division of labour as explanations for the gap.

- The gender gap in pensions is mostly correctly estimated and the size of the gap is not surprising for women. Nevertheless, the large pension disadvantages are perceived as very unfair by the women interviewed, independent of age, place of residence, education level and the personal gendered division of labour of the women interviewed.

- Women identified both the existing gender-specific income gap and the gendered division of labour as explanations for the gap. However, this structural division of labour is hardly questioned by the women themselves. The change in this division of labour is largely delegated to politics and the institutional framework.

- The women interviewed see the reassessment of childcare periods and periods of caring for relatives as well as credits for (a certain number of) years of part-time employment due to childcare as important points for improving women’s income in old age and as a recognition of their unpaid but socially highly necessary work.

4. Measures to increase economic gender equality in old age

The gender pension gap is the result of different factors: (1) The gender imbalances in the labour market concerning salary, working time and typical female (low payed) sectors; (2) The pension design features penalizing women more than men due to the closer link of pension benefits to lifetime contributions. (3) The strengthening of actuarial principles for both pension benefits and contributions.

If the elimination of economic inequalities between women and men is not to take another 170 years, as predicted by the 2016 World Economic Forum, substantial changes are needed.

The past decade is characterized by pension reforms with the goal to increase the financial sustainability of the system in Austria and the other member states of the European Union. Nowadays pension benefits are more closely related to developments in the labour markets. At the same time, labour markets, employment durations, income became more instable[6]. Gainful employment is becoming increasingly important for securing one’s own economic existence. At the same time gainful employment is increasingly losing its function of securing the livelihood in the short- and especially in the long-run (atypical work). Women are particularly affected by this tension.

If the elimination of economic inequalities between women and men is not to take another 170 years, as predicted by the 2016 World Economic Forum[7], substantial changes are needed in the following areas:

Education policy: With the choice of occupation, the income possibilities and opportunities are already largely determined. Even among the younger generation there is still a strongly gender-specific choice of occupation, which is often associated with gender-specific income disadvantages (lower starting salaries) for women.

Labour market measures: In earnings-based pension systems labour market inequalities are the main factors for the huge gender gap in pensions. Here a reduction in the pension disadvantage of women can be achieved primarily through equality measures on the labour market. Changes in many areas are needed like measures to reduce the labour market segregation (promotion of women in technical professions). First, employment policy should further increase labor force participation. Up to now, the high female part-time employment rate increases the number of women with pension entitlements but has a negative effect on the GGP. More gender equality through a reform of revaluations of job values for the purposes of a gender-neutral pay structure according to the social value of jobs (“key jobs” in the corona crisis). The wage policy e.g. transparency of company income structures is also an instrument for empowering women. The reduction of overlong and also health-damaging working hours in conjunction with an increase in part-time hours in the direction of 30-week hours would promote both the reconciliation of employment and unpaid care work and thus strengthening the economic independence of women during working life and in the retirement phase. A 30-hour week would also favor a re-distribution of paid and unpaid work. A better social protection of precarious employment would also promote equality in old age.

Pension scheme: Introducing gender-gap equalizing measures within those pension plans that are based on earnings: This could be a “gender pay gap factor” in the pension calculation formula to revaluation the accumulated credits on the pension account for women with low earnings.

Improvement of the recognition and evaluation of periods of unpaid care work. This would be a compensation for the continuing gendered division of labour at the expense of women, as well as a redefinition of the underlying benefit principle in Austrian pension insurance.

As the international comparison (e.g. the Netherlands) shows occupational pension provision is not a suitable instrument for reducing the gender pension gap, since occupational systems are even more strongly based on gainful employment and reflect and reproduce the gender-specific inequalities in the labour market.

The increase of the retirement age for women up to 65 years will only close the gender gap to a small extent (provident that the economy changes its behavior and is willing to employ older women). The adjustment of earned income is the greater indicator of economic equality between the sexes, also in old age.

[1] The work referred to here was developed within the framework of the EU-co-funded cooperation project “TRAPEZ” (Transparent Pension Future – Securing the Economic Independence of Women in Old Age) coordinated by the Division for Women and Equality in the Austrian Federal Chancellery. An overview of the overall project “Transparent Pension Future” and its partners can be found at https://www.trapez-frauen-pensionen.at/

[2] EIGE (European Institute for Gender Equality) (2015A): Gender gap in pensions in the European Union, https://eurogender.eige.europa.eu/system/files/EIGE_Booklet_Gender_Gap_Pensions_1.pdf

[3] EIGE (European Institute for Gender Equality) (2015A): Gender gap in pensions in the European Union, https://eurogender.eige.europa.eu/system/files/EIGE_Booklet_Gender_Gap_Pensions_1.pdf

Bettio, F., Tinios, P., Betti, G., The Gender Gap in Pensions in the EU, Luxemburg, 2013, https://www.forba.at/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/Gender_Gap_in-Pensions-in-the-EU.pdf

[4] European Parliament (2016): The gender pension gap: differences between mothers and woman without children. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2016/571363/IPOL_STU(2016)571363_EN.pdf

[5] For more details see: Mairhuber, I., Mayrhuber, Ch. (2020): Trapez. Analyse Geschlechtsspezifische Pensionsunterschiede in Österreich. Quantitative und qualitative Befunde. BKA, Wien (im Erscheinen), pp. I4ff. https://www.trapez-frauen-pensionen.at/

[6] Mayrhuber, Ch., Eppel, R., Horvath, Th., Mahringer, H., Destandardisierung von Erwerbsverläufen und Rückwirkungen auf die Alterssicherung, WIFO-Monographien, 2020.

[7] World Economic Forum (2016): The Global Gender Gap Report 2016, Geneva. http://www3.weforum.org/docs/GGGR16/WEF_Global_Gender_Gap_Report_2016.pdf

ISSN 2305-2635

The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Austrian Society of European Politics or the organisation for which the authors are working.

Keywords

Lohnunterschiede, Rentenpolitik, Arbeitsmarktpolitik, Allgemeine Wohlfahrt

Citation

Mayrhuber, C., Mairhuber, I. (2020). The gender pension gap in Austria and Europe. Vienna. ÖGfE Policy Brief, 14’2020