Policy Recommendations

- Transparent and fair distribution rules for state advertisements and new criteria (including quality criteria) for media subsidies are recommended. State aid rules should take into account that a plural and independent media system must be built on three pillars: public service, private-commercial and non-profit community media.

- The EU needs more competences and cooperation in the media policy sector, especially for the fight against the alarming media concentration in the majority of member states. Joint actions on the EU and national level like the implementation of the European Commission’s “Action Plan to support recovery and transformation of the media and audiovisual sectors” are recommended.

- Incentives to increase social diversity in news rooms and self-regulatory instruments such as editorial statutes can help to foster inclusive reporting. Anti-discrimination legislation has a positive impact on the media sector, which can be seen in Sweden’s positive result in the Media Pluralism Monitor. As shown by “Horizon Europe”, EU programmes should prioritize and promote an inclusive society agenda.

Abstract

This Policy Brief discusses the situation of the Austrian media market on the basis of the Media Pluralism Monitor (MPM) 2020 and puts the results in context with the EU-wide situation. The MPM is a scientific tool that evaluates the situation of the media markets in all EU member states based on four areas: fundamental protection, market plurality, political independence, and social inclusiveness. The good news for Austria is: freedom of expression is well protected, journalism is in many ways legally recognized as a public-interest function, media authorities work independently, and there is (still) a varied supply of regional and local media outlets, including a lively community broadcasting sector. On the other hand, there are areas in which Austria was rated particularly poorly in comparison with other EU member states, for example in the indicators editorial autonomy, financing and governance of public service media (PSM), and access to media for women and minorities. EU-wide problematic results can be found in the areas of media concentration and media viability. This Policy Brief suggests a fair distribution of state advertisement and new quality criteria for media subsidies – and the application of existing instruments like the European Commission’s “Action Plan on Europe’s media in the digital decade” to counter media concentration. It is recommended to consider social inclusion as a cross-cutting issue that should be woven into policies such as self-regulatory measures, funding criteria and binding legislation.

****************************

Quo vadis media pluralism in Europe? A contextualization from an Austrian perspective

The European Union as a community of values

The European Union (EU) sees itself as more than just a federation of states in the form of a supranational organization. It is considered to be a community of shared values, which are concluded in the treaties and underpinned by the “Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union”. Roughly speaking, these values take all relevant aspects of human rights and democracy into account. Basically, every country that defines itself as “European” and respects these European values can apply for EU membership so that in 1987, even Morocco applied – without success, as the application was dismissed on the grounds of its geographical location outside Europe. Due to this self-conception the Media Pluralism Monitor is aligned with values that should shape a democratic media system: freedom of expression, plurality, independence, and social inclusiveness.

European media policy

Although media policy is a fundamental issue for European democracies, the EU has only limited competence in this field, and the policy area is segmented into different approaches. Scholars divide the Union’s media policy into four strands. First, there is the Audiovisual and Media Services Directive, which has been implemented in the legislation of all member states with the aim of creating an internal market for audiovisual services. The second strand is made of several EU programmes like “MEDIA”, as part of “Creative Europe”, which mainly provide funds to the European film and audiovisual industry. However, in 2020 the European Commission published a call for media pluralism and freedom projects to support investigative journalism as well, and for the new Multiannual Financial Framework 2021–2027, the plan for “Creative Europe” is to focus on media pluralism, media literacy, and quality journalism. Third are non-binding policy recommendations by the European Commission for media pluralism and media literacy, some of which will be discussed in this Policy Brief. These recommendations could be used as criteria for calls for upcoming projects and initiatives. The fourth strand is an external European media policy for when the EU represents economic/cultural interests of the member states on an international level (e.g. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), World Trade Organization (WTO)) (Donders et al., 2014).

In Ursula von der Leyen’s European Commission, the topic of media freedom and pluralism has been given a new priority and has been placed at the highest level. The European Commissioner, Věra Jourová, Vice-President for Values and Transparency, is responsible for these issues. In her hearing in the European Parliament, Jourová underlined the importance of media pluralism as a cornerstone of democracy and her plans to fund investigative journalism projects. Together with von der Leyen she emphasized the importance of the “Media Pluralism Monitor” (MPM) as an instrument to detect problems concerning the media systems of the EU member states. Consequently, in the first “Rule of Law Report”, the European Commission refers to the MPM 2020 and its country reports to assess the situation of media pluralism in the EU. The ambitions of the von der Leyen Commission on media freedom and pluralism can also be recognized by the crucial role media have in current Action Plans such as “Human Rights and Democracy” or “Combating COVID-19 Disinformation”.

This leads to the question: Quo vadis media pluralism? For this Policy Brief, the main focus is on the Austrian results in a European context and relies on the Media Pluralism Monitor 2020.

The Media Pluralism Monitor

The MPM could be viewed as a clinical thermometer of European media pluralism and also of democracy itself.

The MPM is a European research project developed and conducted by the European University Institute, which analyses the status quo of the European media systems from many perspectives. The foundations of the MPM, which is co-funded by the EU, were laid in 2009 and tested in a project environment in 2014 and 2015. Before 2020, it was already published in 2016 and 2017. Every EU country (and, in 2020, Turkey and Albania) has its own experts to evaluate the specific situation. The MPM covers four areas: fundamental protection, market plurality, political independence, and social inclusiveness, each including five indicators, with every indicator including 40 to 58 questions. The combination of the risk assessments based on the indicators results in a risk factor for the respective area. The risk scores are grouped as low risk (from 0% to 33%), medium risk (from 34% to 66%), and high risk (from 67% to 100%). The MPM could be viewed as a clinical thermometer of European media pluralism and also of democracy itself.

The four areas

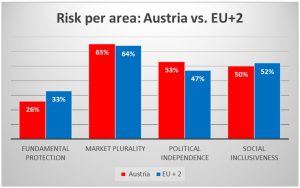

Source: Florian Woschnagg / Data: Center for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom. (2020). MPM 2020 Interactive. https://cmpf.eui.eu/mpm-2020-interactive/

As already mentioned, the MPM 2020 covers four areas to analyze media pluralism. The following provides a brief overview of them.

First, fundamental protection: The indicator of fundamental protection analyzes several fundamental aspects of risk for a pluralistic democracy, for instance the rules and their effectiveness for the protection of freedom of expression and the right to information or measures to ensure the safety of journalists and the independence of media authorities. Overall, Austria ranks in this category with a risk of 26%, which is lower than the EU+2 average risk of 33%. Austria achieves its best results of the report in the area of fundamental protection.

Second, market plurality: Besides indicators of transparency of ownership, media concentration, market viability, and commercial influence over editorial content, this section also evaluates the impact of digital platforms on media pluralism. In general, Europe’s situation in this area can be described as critical. The average risk for the EU+2 is very high, at 64%. Compared to 2017, this means an increase of about 10%. In the whole EU, there is no country with a low-risk result. With a risk level of 65%, Austria just barely reaches the medium-risk range and scores slightly higher than the EU average in this category.

Third, political independence: Indicators like political independence and editorial autonomy evaluate the political influence on media and their content. Moreover, this section considers the instruments and rules of distribution of state resources to media and the independence of the countries’ public service media (PSM) funding and governance. Overall, with 53%, Austria has a higher risk level than the EU+2, with 47%.

Fourth, social inclusiveness: This area deals with the inclusiveness of media systems for women, minorities, and people with disabilities. Furthermore, access to media for local communities and community media as well as media literacy is examined. Besides the good results in line with the other EU countries in the fundamental protection section, Austria has another good result for the communities and community media indicator (more below). The overall risk for this area for the EU+2 is 52%; Austria reaches a slightly better result with 50%, which means medium risk.

Austria’s stable basis

At the indicator level, Austria achieved three of the four low-risk results in the “fundamental protection” area and one in the area “social inclusion”. For the indicator “journalistic profession, standards, and protection”, which examines access to the profession, working conditions, and protection of sources, Austria shows a risk of 23% (EU-wide: 33%). Professional associations like the GPA-DJP (union for private employees and employees in print, journalism, and paper) and the Press Club Concordia play an important role for professional standards and editorial independence in Austria. However, the Austrian report emphasizes that they should pay more attention to freelancers and new members of the journalistic profession like bloggers or social media activists.

Austria achieves its lowest risk factor (3%) for the indicator “independence and effectiveness of the media authority”. The duties, power, and responsibilities of the communications authority KommAustria (which is operationally supported by the Regulatory Authority for Broadcasting and Telecommunications RTR) are based on the KommAustria Act of 2001. KommAustria is “highly respected” for its independent status which is legally guaranteed, in terms of independent decision making, since October 2010 (Seethaler & Beaufort, 2020, p. 10). EU-wide, there are only seven countries facing a medium risk; the rest of the EU member states rank in the low-risk area.

Internet connectivity in the European Union is developing well. In comparison to 2017, the MPM reports a general decrease in risk from 43% down to 38%. Austria has a lower risk level (21%) than the EU-wide average, which means that a large part of the population has a broadband connection. The only country facing a high risk for this indicator is Portugal: only 75% of the population has broadband internet.

According to the Council of Europe, community media play an important role for an active citizenry, empowerment, and social inclusion.

While Austria was in line with most of the EU countries regarding the low-risk results in the area of fundamental protection, Austria has one exceptionally good result (19%) for “access to media for local/regional communities and for community media”, an indicator part of the area of social inclusiveness. The WHO requires its member states “to empower communities” as a measure against disinformation and fake news and to foster a resilient society (2020). Austria supports local and regional communities in various ways: In all federal states the public broadcaster runs regional radio stations and TV news formats. By law, local and regional media have access to media platforms, and TV and radio frequency allocation is regulated by public tendering; subsidies for private broadcasters are subject to the supply of regional and local programmes. Moreover, Austria has a relatively large range of community media (14 radio and 3 TV stations) which assume important democratic functions (Peissl et al., 2020) – articulation, participation, local information, media education – which public service and commercial media are not able and/or not expected to fulfil to a similar degree (Seethaler & Beaufort, 2017). According to the Council of Europe, community media play an important role for an active citizenry, empowerment, and social inclusion. Similarly, the European Parliament states in a resolution that community media promote media pluralism and assume several important roles for strengthening minorities and diversity as well as, among others, media literacy.

High-risk areas

The Austrian MPM report provides a main diagnosis of this situation: lacking or weak legislation.

Unfortunately, Austria faces a risk level above 60% for seven indicators: news media concentration, online platform concentration, media viability, editorial autonomy, independence of PSM governance and funding, access to media for minorities, and access to media for women.

In Austria, all concentration measurements for ownership and audience concentration in the audiovisual, radio, and newspaper markets are between 72% and 89% (data from 2018) and therefore far too high to be acceptable from a democratic point of view. The Austrian MPM report provides a main diagnosis of this situation: lacking or weak legislation. In a recent published resolution, the European Parliament stresses that “excessive media concentration threatens pluralism” (European Parliament, 2020), and emphasizes that, especially when it comes to the fight against disinformation, a highly concentrated market is problematic. Therefore, the EU member states are required to cooperate and take measures against an excessive media concentration, as can be found in the plan on “Europe’s Media in the Digital Decade”. It’s time to take action: The EU-wide average for the news media concentration indicator is 80%. The best results on media concentration can be found in Greece (52%) and Germany (56%). The countries have certain legal thresholds on media concentration in common by defining the “dominant position” on the media market.

It’s time to take action: The EU-wide average for the news media concentration indicator is 80%.

The indicator “online platform concentration and competition enforcement” is new to the MPM 2020 and deals with two sub-indicators: (a) gateway to news and (b) competition enforcement. EU-wide, the average risk level is, with 72%, in the high-risk area. Also, Austria faces a high-risk level of 75%. The main reason here are lacking regulations in the face of media change. The main way users access news online is via news aggregators and digital intermediaries such as search engines and social media, a fact that Seethaler & Beaufort (2020, p. 18) call “alarming”. The lowest risk level can be found in Denmark (40%), especially due to the efforts in the area of competition enforcement.

Several efforts have been made to reach a digital tax on the EU level; however, so far, this policy area seems to be mainly in the member states’ competence. France was a pioneer in this subject and already introduced such a taxation scheme called “GAFA”, which targets companies like Google, Amazon, Facebook, and Apple. Austria also introduced a 5% digital tax on online advertising provided by tech giants like Facebook and Google; the revenues from this tax will be used to support digital transformation.

For the indicator “media viability”, Austria faces a risk level of 65%. Overall, the number of journalists is decreasing (Kaltenbrunner et al., 2020), and the MPM report criticizes the rules on the allocation of federal subsidies, from which especially tabloids and commercial broadcasters benefit, while non-commercial media do not get an adequate share. In 2020, additional Corona funding was granted €9,7 million for daily newspapers and €3 million for weekly, regional and online newspapers (RTR). The award criteria were strongly oriented to the production conditions of tabloid and free newspapers (Kaltenbrunner, 2020).

About 40% of the advertising revenues in Austria are achieved by the big platforms Google, Facebook, and Apple (Fidler, 2020). According to a study of the Reuters Institute, only 11% of users are willing to pay for digital news media (2019). In the European comparison, Greece faces the highest risk level EU-wide (79%), and, because of a lack of public support for non-PSM media, the same applies to Ireland (75%). Only Poland (21%) and Hungary (27%) achieved a low-risk indication. In both countries, however, (in)direct federal subsidies play an essential role, and especially in Hungary, state advertisement revenues of about €450 million in 2019 brought media companies into a problematic dependency relationship.

Besides political decisions of media regulators and campaigns against journalists, Hungary faces a high risk of 92% because of the importance of state advertisement for the media.

This circumstance can also be seen in the “editorial autonomy” indicator. Besides political decisions of media regulators and campaigns against journalists, Hungary faces a high risk of 92% because of the importance of state advertisement for the media. Austria also shows a high risk (75%) for this indicator. In addition to lacking regulations on preventing influence on appointments of editors-in-chief and lacking editorial statutes, this is due to the kind of distribution of state advertisements. The Austrian state subsidies in 2018 were only about €40 million; the unregulated distributed state advertisements amounted to €170 million, an upward trend. Transparent and clear criteria on the distribution are needed here. In the Rule of Law Report, the European Commission is concerned about the lack of rules on the allocation of state advertisements in Austria and Hungary. Low-risk indications for “editorial autonomy” can be found in countries with distinct self-regulatory mechanisms like Germany (3%) or the Netherlands (25%).

The lowest risk levels can be found in Sweden and the Netherlands: Both countries implemented rules to avoid direct political influence on the appointment of the PSM management boards.

Austria has a high-risk score (67%) for the indicator “independence of PSM governance and funding”. The main problem is the political influence on the appointment of the “Stiftungsrat” (main duties: appointment of high officials, control of budget and financial conduct). A total of 15 out of 35 members are appointed by the federal government; several other members can be assigned to parties. High political influence on the appointment of the PSM board also applies to other high-risk countries like Greece (75%), Croatia (67%), and Luxembourg (67%). The lowest risk levels can be found in Sweden and the Netherlands: Both countries implemented rules to avoid direct political influence on the appointment of the PSM management boards.

In the area of “social inclusiveness”, Austria shows problematic results with regard to two indicators: “access to media for women” (63%) and “access to media for minorities” (71%). Women are underrepresented in Austrian media when it comes to airtime, interviewed experts, and staff (particularly of newspaper editorial offices and management boards of some commercial broadcasters), a situation similar to that in the countries with the highest risk scores, which are Cyprus and the Czech Republic (each 88%). Sweden represents a best practice for this indicator: The far-reaching gender equality regulations also apply to the media sector.

In the area of “social inclusiveness”, Austria shows problematic results with regard to two indicators: “access to media for women” (63%) and “access to media for minorities” (71%).

In 2019, the OSCE outlined the importance of media access for minorities to mainstream media but also to “autonomous discursive spaces”. These spaces should not lead to an isolation of minorities but to them becoming part of a “diverse society” (Tallinn Guidelines, 2019, p. 29). In Austria, there are no regulations for non-recognized minorities, and the airtime for legally recognized minorities in PSM is very limited. Only community media give minorities a reasonable share of representation – also when it comes to the producers of content. In the Netherlands and Estonia, minorities get airtime in the PSM regardless of whether they are recognized or not. In general, social inclusion should be seen as an agenda to be woven into all policies, as shown by the new “Horizon Europe” programme: The European Union prioritizes the goal of a more inclusive society and wants to promote research to overcome discrimination and racism and to promote gender equality and dialogue.

Pan-European cooperation is needed

Democracy needs free and pluralistic media. Austrian politics is urged to strengthen both independence and pluralism (at the market level and at the social level). The European component must not be overlooked: In times of global media and globally acting media companies as well as globally prevalent problems such as fake news, disinformation, and hate speech, initiatives must be found on a European level. Moreover, many countries in the EU face similar problems, especially regarding media concentration. In solving such problems, bilateral and multilateral exchanges can make a valuable contribution. The results of the MPM can help to recognize and analyze problems and start innovative and urgently needed initiatives for a sound media environment. The European Union already has a set of instruments – combined, they could be a foundation to implement sustainable initiatives on a European level. The plan “Europe’s Media in the Digital Decade” (among others) and EU funds such as “Horizon Europe” provide the impetus for governments, businesses, civil society, and researchers to start inclusive projects and initiatives.

Responsible of the Austrian Report of the Media Pluralism Monitor are Josef Seethaler and Maren Beaufort, Institute for Comparative Media and Communication Research at the Austrian Academy of Sciences and the University Klagenfurt

Seethaler, J., & Beaufort, M. (2020). Monitoring media pluralism in the digital era: Application of the Media Pluralism Monitor in the European Union, Albania and Turkey in the years 2018-2019. Country report: Austria. European University Institute. https://cadmus.eui.eu/bitstream/handle/1814/67793/austria_results_mpm_2020_cmpf.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Center for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom. (2020). MPM 2020 Interactive. https://cmpf.eui.eu/mpm-2020-interactive/

Country reports of the MPM can be found at https://cmpf.eui.eu/mpm2020-results/

Donders, K., Loisen, J., & Pauwel, C. (2014). The Palgrave handbook of European media policy. In K. Donders, J. Loisen & C. Pauwel (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of European media policy (pp. 1-19). Palgrave Macmillan.

European Parliament. (2020, 11th of November). Media freedom: EP warns of attempts to silence critics and undermine pluralism. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/press-room/20201120IPR92117/

Fidler, H. (2020, 3rd of December). Grünen-ORF-Rat Lothar Lockl: “Medienstandort Österreich massiv in Gefahr”. https://www.derstandard.at/story/2000122184478/gruenen-orf-rat-lothar-lockl-medienstandort-oesterreich-massiv-in-gefahr

Kaltenbrunner, A. (2020). Scheinbar transparent II. Eine Analyse der Inserate der Bundesregierung in Österreichs Tageszeitungen und der Presse- und Rundfunkförderung im Pandemiejahr 2020. Medienhaus Wien. http://www.mhw.at/cgi-bin/page.pl?id=383

Kaltenbrunner, A., Lugschitz, R., Karmasin, M., Luef, S., & Kraus, D. (2020). Der österreichische Journalismus-Report. Eine empirische Erhebung und eine repräsentative Befragung. Facultas.

OSCE. (2019, 1st of February). The Tallinn guidelines on national minorities and the media in the digital age. https://www.osce.org/hcnm/tallinn-guidelines

Peissl, H., Seethaler, J., & Biringer, K. (2020). Public Value des nichtkommerziellen Rundfunks. RTR.

https://www.rtr.at/medien/aktuelles/publikationen/epaper/StudiePublicValue-2020-ePaper.de.html

Reuters Institute. (2019). Digital news report 2019. Oxford University. https://www.digitalnewsreport.org/

RTR. (2020, 24th of August). Außerordentliche Förderung gemäß § 12b PresseFG im Jahr 2020. https://www.rtr.at/medien/was_wir_tun/foerderungen/pressefoerderung/ausserordentliche_foerdermassnahmen2020.de.html

Seethaler, J., & Beaufort, M. (2017). Community media and broadcast journalism in Austria: Legal and funding provisions as indicators for the perception of the media’s societal roles. Radio Journal: International Studies in Broadcast & Audio Media, 15(2), 173-194. https://doi.org/10.1386/rjao.15.2.173_1

WHO. (2020, 23rd of September). Managing the COVID-19 infodemic: Promoting healthy behaviours and mitigating the harm from misinformation and disinformation. https://www.who.int/news/item/23-09-2020-managing-the-covid-19-infodemic-promoting-healthy-behaviours-and-mitigating-the-harm-from-misinformation-and-disinformation

ISSN 2305-2635

The views expressed in this publication are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Austrian Society of European Politics or the organisation for which the author is working.

Keywords

media pluralism, fundamental protection, market plurality, political independence, social inclusiveness, democracy, competences, Austria, European Union

Citation

Woschnagg, F. (2021). Quo vadis media pluralism in Europe? A contextualization from an Austrian perspective. Vienna. ÖGfE Policy Brief, 09’2021