Policy Recommendations

- Change of perspective: Outmigration is a challenge for sending regions, but also a chance. For young people it is a way to unfold their potential.

- Young people’s location choices are complex and are not only based on economic factors, but also on cultural and social amenities. Regional development strategies aiming to attract young people need to take soft location factors into consideration.

- To counteract outmigration, regions not only need to focus on how to trigger return migration or to keep their younger population, but also on how to attract newcomers

Abstract

Since fertility rates in most of Europe’s regions are stagnating, migration is the main driver of the population growth in the European Union. Nevertheless, regions of the European Union are experiencing different patterns of population development: between 2000 and 2011 population growth mainly took place in economic prosperous regions in the European core or regions with prosperous labour markets, while peripheral regions in the East, West and North, but also within inner-European peripheries (Germany, Austria, France) experienced population decline, mostly as a result of outmigration. Migration between and within the countries of the European Union as well as from outside the European Union are relevant to the population growth of Europe’s regions. In shedding light on the characteristics of migrants moving within and to EU’s regions, it becomes obvious that migration is a selective phenomenon. Migration and mobility is especially prevalent among younger people, mainly those between the ages of 18 and 34. Life course transitions are common in this age group, supporting different mobility patterns. For many European regions the loss of (young) people due to low fertility rates and emigration of the young and highly educated leads to negative consequences for the regional development. This policy paper offers perspectives on the phenomena that could help regions to develop strategies to manage potentially negative consequences. There is no one-size-fits-all-strategy on how to tackle youth outmigration. But understanding and accepting the drivers can be a starting point for turning outmigration into an opportunity for renewal.

****************************

Outmigrating youth: A threat to European peripheries?

Migration is the main driver of population development in the EU

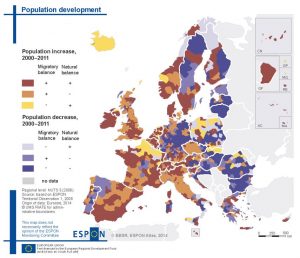

Today, migration is the main component of the European Union’s population development (Dijkstra et al. 2017). Fertility rates in most European countries are below the level of natural replacement. Therefore mainly regions that are experiencing more immigration than emigration are also experiencing a growing population (see map 1). Only a few regions within Europe are able to show a positive natural population development, while having no positive migration balance. In Austria, population growth is mainly attributed to international immigration, since the natural population development is stagnating.

Map 1: Population development by components, 2000–2011, Source: Espon Atlas 2014: http://atlas.espon.eu/ (14.04.2019)

Immigration is triggered by economic prosperity, possibilities on the labour market and educational opportunities. The patterns of population change between 2000 and 2011 show that population growth mainly took place in economic prosperous regions in the European core, or in regions with prosperous labour markets, while peripheral regions in the East, West and North, but also within inner-European peripheries (Germany, Austria, France) experienced population decline. Generally it is urban agglomerations that experience immigration, while rural areas or former industrial areas within Europe suffer ongoing outmigration[1] – a trend that applies to internal and international migration. However, with the 2008 crisis and the increase of third country migration to Europe, the patterns have changed (see Eurostat 2018). Peripheries in the South have started to lose population, while countries such as Sweden and Norway show population gains also in remote northern regions. Still, migration has remained the main driver of population development.

The largest groups of EU internal moves are from the new member states, mainly Romania and Poland, but also from other regions that are suffering from the economic crisis in Southern Europe.

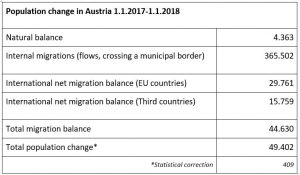

To a large extent, the regions in Europe showing a positive net migration balance are experiencing immigration from other parts of the European Union (EU internal migration) or internal migration from other parts of the same country, as it is the case in Austria (see table 1). But population growth in European Union regions is also triggered by international migration. Since the enlargement of the EU in 2004 and 2007, and the economic crisis of 2008, migration within the EU has intensified (King and Williams 2017). The largest groups of EU internal moves are from the new member states, mainly Romania and Poland (ibid.), but also from other regions that are suffering from the economic crisis in Southern Europe. In Austria, in 2017 international migration flows mainly came from Romania (+8,416), Syria (+5,842), Germany (+5,587) and Hungary (+5,550) (Statistik Austria 2019). In total, a net number of 49,630 people has been observed arriving to Austria, with 29,761 of them coming from other EU countries. Within the country’s borders 365,502 moves took place in the year 2017, where people have changed their residence by crossing a municipal border. Most of them where directed towards urban agglomerations (ibid.).

In Austria, in 2017 international migration flows mainly came from Romania (+8,416), Syria (+5,842), Germany (+5,587) and Hungary (+5,550).

Table 1: Population in Austria by components, 1 Jan. 2017–1 Jan. 2018, Source: Statistik Austria (Statcube, 14.04.2019)

Selective migration: Mobility as a phenomenon of the younger ages

Three main types of young migrants can be distinguished: Labour-motivated youth migrants, educations-induced youth migrants and migration caused by family formation.

Migration is a selective phenomenon since not all subgroups of a population have the same prevalence of being mobile. Especially the age of a person affects the possibility to migrate. Since most significant life course transitions that trigger migration and occur when people are younger, a high number of migrants are young, aged between 18 to 34, experiencing the transition from school to higher education, the transition from education to employment and the transition from living at home with the family to living independently (King et al. 2016). Deriving from these transitions, three main types of young migrants can be distinguished: Labour-motivated youth migrants, educations-induced youth migrants and migration caused by family formation. Especially migration within the European Union can mostly be traced back to these migrant groups, as EU citizens benefit from the freedom of movement, labour and residence.

Labour-motivated youth migration can serve as a strategy for handling increasing labour market insecurities and fewer employment opportunities, as well as to overcome payment differentials between different regions. Access to the European market has influenced employment opportunities, especially for Eastern European countries. Labour-motivated youth migration can be observed internationally as well as internally.

Moreover, increasing tertiary education has led to an increase of youth mobility within the EU and globally. Education-induced youth migration can take place at different levels of education and between various regional and national boundaries. Nevertheless, it is mostly connected to tertiary educational attainment in the form of both internal and international movements. Erasmus mobility schemes, the expansion of study programmes taught in English, as well as the development of the university sector as a global market have led to a higher prevalence of studying abroad (King et al. 2016). Studying in a foreign country can be the beginning of an international career and the starting point for a longer period of living abroad. Similarly it can be a strategy to improve on one’s job opportunities back home.

Further, when young the life stage of family formation takes place, which is often connected to a change of residence. Setting up an independent residence, followed by family forming events such as marriage, partnership union, cohabitation or giving birth often triggers internal migration. In addition, the creation of partnerships across borders due to cosmopolitan lifestyles is playing an increasing role in international migration decisions.

The increasing mobililty of young people is not only due to life course transitions, but is also linked to the fact that young people are growing up in an increasingly mobile world. It is a world where migration and mobility become important individual strategies for managing opportunities and scarcities (Veale and Donna 2014). In the transition to adulthood, living abroad is of major importance for globally oriented young people (Beck and Beck-Gernsheim 2002). In addition to socio-structural circumstances affecting young people’s mobility patterns, the migration of young people is influenced by socio-cultural processes of individualization. This can be seen in aspirations – but also the demand – for self-realisation, life-style choices and a “thirst for adventure”. At the individual level, migration is usually connected to the improvement of the migrant’s living situation. For young people the cost of migration is often low, while investing in education or a career abroad can lead to many kinds of benefits, including financial ones.

Mainly peripheral regions in Europe are affected by youth outmigration

While the increasing mobility of young people within the EU provides greater chances for the young people themselves, such mobility causes negative consequences at the regional level.

Migration is not only selective at the individual level, but also at the spatial level. Today, the landscape of migration patterns reveals a clear picture of which regions are (un)desired by young people. Each region offers different chances with regard to job possibilities, education and living conditions. This uneven distribution of life chances fosters migration decisions of people. Regions that lack opportunities, as for example in their labour market, often experience outmigration (Faggian et al 2017).

While the increasing mobility of young people within the EU provides greater chances for the young people themselves, such mobility causes negative consequences at the regional level. Not only is emigration connected to the losses in productivity, human capital and innovation –– the so-called brain drain – it also means that potential parents are leaving and therefore a negative population development is effected in two ways.

Often accompanying such negative overall population development in regions affected by outmigration are negative financial effects. This is because population development often is the basis for assessing the financial distribution. Increasing outmigration and population loss therefore constrain future development possibilities. Further, a critical mass of people not only creates a financial basis for a vital community, but also its social basis. Moreover, small communities are uninteresting for public and private investments. Emigration also intensifies the process of demographic ageing, which leads to shrinking labour forces and increasing demands for geriatric care.

Tackling the consequences of emigration

The European regions that are experiencing depopulation are often regions with scarce labour market options or economies in transition. This is the case for many rural areas or former industrial areas. Strategies for tackling outmigration thus often focus on economic investments. Although there is often a correlation between negative economic development and decreasing population, there are certain regions that have been able to offer economic perspectives to their population despite population decline caused by outmigration. Typical for this type of regions are those with mono-structural economies (e.g. in the tourism or industrial sector) (Dax and Fischer 2017).

Young peoples’ decisions about where to settle and live are not only influenced by finding a job, but also by having a variety of career opportunities, a work-life balance, affordable housing, a high quality of life, as well as a broad social and cultural infrastructure.

Regions with comparably stable economies that are nonetheless affected by depopulation reveal the complex drivers shaping young people’s location choices. These involve more than just economic factors. Young peoples’ decisions about where to settle and live are not only influenced by finding a job, but also by having a variety of career opportunities, a work-life balance, affordable housing, a high quality of life, as well as a broad social and cultural infrastructure. All of these factors are strongly related to aspects of lifestyle that shape young people’s desires and aspirations and that often lead to young people leaving their – often rural – homes and moving to urban areas (Ní Laoire 2000; Pedersen and Gram 2018; Stockdale 2004; Van Hear et al 2017). But what can regions do in order to stay attractive for young people? Is there any way to stop emigration?

Competition for the “resource” of young people will intensify

In knowledge-based societies, the resource of young people, especially educated young people, is in high demand for regional economies world-wide. With decreasing fertility rates, the competition for talented people will intensify even more in future. Moreover, this will evolve on a global scale. If regions want to be competitive, they must invest into their social and cultural infrastructure and remain open towards a diverse society and the different lifestyles this represents.

Nevertheless, for some regions the mobility of young people will most certainly mean sustained population decrease. Especially in regions where economic transitions are leading to population decline, turning around population decline will be difficult. For outmigration regions to react to negative population development, planning strategies are needed that focus on adaptation and stabilisation (see also Schorn and Gruber 2018).

The potential of return and remittances

Although the loss of financial and human capital is very difficult to deal with, emigration is not always a dead-end road. For a long time, migration streams have been considered mono-directional. In reality, however, it has become ever more common for people to undertake multiple moves over their lifetime (King and Skeldon 2010). Return migration, but also different forms of circular migration and living at multiple places have led to the possibility of considering migration a form of bottom-up regional development strategy that leads to networks and flows of capital and knowledge (Faggian 2017 et al. 2017, SVR 2016, Fassmann et al. 2018).

The potential of immigration

It must be accepted that it is not enough for regions to focus solely on gaining back their populations that have left. For many regions, a positive migration balance is needed in order to return to a positive population development. Due to low fertility rates, in most regions of the EU and in Austria, no natural population growth can be observed. More immigration will therefore be needed for any growth to occur. This implies that international immigration needs to be targeted by currently depopulating regions. With increasing demographic ageing, the size of labour force will further decrease – especially since the “Baby-Boomer Generation” is nearing retirement age. This development will even intensify the need for young population in the labour market.

The need for a change of perspective

It also must be accepted that migration and mobility today play an important role in young people’s biographies. The outmigration of young people should not be prevented in order to save regions from losing population. From neither an individual nor a legal perspective can it be considered a legitimate solution to attempt to alter human behaviour and force people to stay where they are. On the contrary, regions and regional actors should learn to profit from this ongoing development and become aware of the chances that come with it – both for regions as well as individuals. Although most authorities today see outmigration as a threat, it also offers the possibility of focussing on opportunities for reshaping its regional development strategies. If regions start accepting migration as an inevitable process of modern society instead of being threatened by it, outmigration can be turned into an opportunity.

Statistik Austria, Statcube: www.statcube.at (11.04.2019)

Statistik Austria (2019): Wanderungen mit dem Ausland (Außenwanderungen). http://www.statistik.at/web_de/statistiken/menschen_und_gesellschaft/bevoelkerung/wanderungen/wanderungen_mit_dem_ausland_aussenwanderungen/index.html (11.04.2019)

Eurostat (2018): Statistical Atlas. http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistical-atlas/gis/viewer/?mids=BKGCNT,C02M01,CNTOVL&o=1,1,0.7&ch=POP,C02¢er=50.03696,19.9883,3& (14.04.2019)

Espon Atlas (2014): Mapping European Territorial Structures and Dynamics. http://atlas.espon.eu (11.04.2014)

[1] Definition of “outmigration/emigration” – a region is defined as an outmigration region, when the number of people moving away exceeds the number of people moving in (negative net-migration balance). Although the two terms are sometimes used synonymously, emigration is more widely used for international migration (the permanent crossing of a national state border), outmigration also includes internal migration (so permanent migration within a country) (see e.g. Barcus and Halfacree 2018, 93). In the last decades migration between EU countries has started to be considered sort of “internal” migration, due to the freedom to move, settle and work. In the last years EU internal migration has been increasingly described as “mobility” rather than migration; migration has become the term used mainly for third-country immigration (see further King and Williams 2017, 4). Here, we use the word “outmigration” since it subsumes EU internal as well as global migration and also country-internal mobility, such as rural to urban migration.

- Barcus, H.R. and K. Halfacree (2017): Lives across Space: An Introduction to Population Geography. Routledge. New York.

- Beck, U. and E. Beck-Gernsheim (2002): Individualization. Institutionalized Individualism and its Social and Political Consequences. Sage. London.

- Dax, T. and M. Fischer (2018): An Alternative Policy Approach to Rural Development in Regions Facing Population Decline. European Planning Studies Vol 26(2): 297-315. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2017.1361596

- Dijkstra, L., European Commission, Directorate-General for Regional and Urban Policy (Eds.) (2017): My Region, My Europe, Our Future. Seventh report on economic, social and territorial cohesion. Brussels. http://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/en/information/cohesion-report/

- Faggian, A., I. Rajbhandari and K. R. Dotzel (2017): The Interregional Migration of Human Capital and Its Regional Consequences: A Review. Regional Studies 51 (1): 128–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2016.1263388

- Fassmann, H., E. Gruber, E. and A. Németh (2018): Conceptual overview of youth migration in the Danube region. YOUMIG Working Papers, No.1. http://www.interreg-danube.eu/uploads/media/approved_project_output/0001/13/85f6d084e0981d440cf80fcda5f551c8b6f97467.pdf

- King, R. (2002): Towards a new map of European migration. Population Space and Place 8(2): 89-106 https://doi.org/10.1002/ijpg.246

- King, R. and A.M. Williams (2018): Editorial Introduction: New European youth mobilities. Population Space and Place 24(1): e2121 https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.2121

- King, R., A. Lulle, L. Morosanu and A. Williams (2016): International Youth Mobility and Life Transitions in Europe: Questions, Definitions, Typologies and Theoretical Approaches’. Working Paper No. 86. University of Sussex. Sussex Centre for Migration Research.

- King, R. and R. Skeldon (2010): ‘Mind the Gap!’ Integrating Approaches to Internal and International Migration. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 36(10): 1619-1646 https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2010.489380

- Ní Laoire, C. (2000): Conceptualising Irish Rural Youth Migration: A Biographical Approach. International Journal of Population Geography 6 (3): 229–43 https://doi.org/10.1002/1099-1220(200005/06)6:3<229::AID-IJPG185>3.0.CO;2-R

- Pedersen, H. D. and M. Gram (2018): ‘The brainy ones are leaving’: the subtlety of (un)cool places through the eyes of rural youth. Journal of Youth Studies. Vol 21(8):620-635 https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2017.1406071

- Stockdale, A. (2004): Rural Out-Migration: Community Consequences and Individual Migrant Experiences. Sociologia Ruralis 44 (2): 167–94 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9523.2004.00269.x

- Schorn, M. and E. Gruber (2018): Jugend in Bewegung. Motive, Auswirkungen und potenzielle Steuerungsmöglichkeiten von Jugendmigration aus Perspektive der geographischen Migrationsforschung. In: Fritz, J. and N. Tomaschek (2018): In Bewegung Beiträge zur Dynamik von Städten, Gesellschaften und Strukturen. University – Society – Industry, Band 7, Wien. 165-183

- SVR (=Sachverständigenrat deutscher Stiftungen für Integration und Migration) (2016): Viele Götter, ein Staat: Religiöse Vielfalt und Teilhabe im Einwanderungsland. Jahresgutachten 2016 mit Integrationsbarometer. SVR GmbH. Berlin.

- Van Hear, N., O. Bakewell and K. Long (2018): Push-Pull plus: Reconsidering the Drivers of Migration. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies. Vol 44(6):927-944 https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2017.1384135

- Veale, A. and G. Dona (2014): Child and Youth Migration. Mobility-in-migration in an era of Globalization. Palgrave Macmillan. London.

ISSN 2305-2635

The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Austrian Society of European Politics or the organisation for which the authors are working.

Keywords

Migration, Youth, EU, Youth Migration, Outmigration, Intra-EU Mobility, Regional Development

Citation

Gruber, E., Schorn, M. (2019). Outmigrating youth: A threat to European peripheries? Vienna. ÖGfE Policy Brief, 17’2019