Policy recommendations

- The support for EU-membership is high in Central Europe, as are the levels of expectations and frustrations. The EU is expected to successfully solve the problems at hand. Yet, reforming the functioning of the EU – and naming those who are detrimental to these changes – should also be at the centre of the debate.

- The risks and costs of entering a spiral of renationalisation should be made clear and awareness raised that nationalistic discourse is rather about obstructing common European policies than solving cross-border problems.

- The importance of the foundations of European integration, in particular its values and the rule of law, need to be constantly emphasised. Across the EU more support should be given in particular to freedom of speech and of the media.

Abstract

Nationalist-populistic discourse is gaining momentum in many EU-member states, not least in the Central European region. European approaches to cope with the manifold challenges the EU and its members are currently facing, are meeting resistance, while trust in the capacity and ability of common European cross-border solutions is rather low. Trends to recur to a national political agenda have the potential to jeopardise the cornerstones of European integration and democracy and, thus, diminish the EU´s unity, its global weight and its credibility. A joint project by the Austrian Society for European Politics, the Center for European Neighborhood Studies (Central European University Budapest), EUROPEUM Prague, the Faculty of Social Sciences (University of Ljubljana) and GLOBSEC Policy Institute Bratislava examines on the basis of representative opinion polls if people in Austria, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Slovakia and Slovenia buy into anti-EU rhetoric and to what extent the respective national EU debate affects EU public opinion. The project “Anti EU-rhetoric against national interests? Nationalistic populism and its reception in Central Europe” is co-funded by the Europe for Citizens programme of the European Union.

****************************

Nationalistic populism and its reception in Central Europe

Public opinion in Central Europe

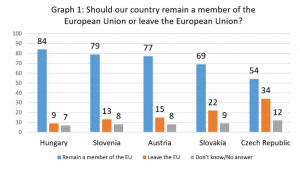

The survey[1] reveals that – despite an increased nationalistic discourse over the last years – people’s willingness to leave the EU is rather low. Contrary to some expectations, Hungarians are the strongest supporters of EU membership, followed by Slovenes, Austrians and Slovaks. Respondents from the Czech Republic are by far the most sceptical.

A majority in all five countries associates EU membership, albeit to varying degrees, with benefits. This is especially true for the economic welfare of the country – strongest in Hungary, weakest in the Czech Republic and Slovakia; in a similar degree for the country as a business location; and in lesser degree for its security – strongest in Slovenia, weakest in the Czech Republic and, the Czech Republic being an exception -, its political weight – strongest in Slovakia, Hungary and Slovenia. Respondents say that the EU plays a positive role in promoting mutual understanding and cooperation between the member states – strongest in Slovakia – as well as protecting democracy and human rights – strongest in Slovakia and Czechs being the most sceptical again.

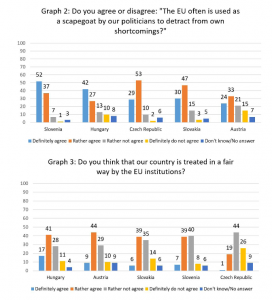

People remain quite pragmatic and critical towards anti-EU rhetoric and say that national politicians use the EU as a scapegoat.

People remain quite pragmatic and critical towards anti-EU rhetoric and say that national politicians use the EU as a scapegoat. This applies in particular to people in Slovenia, where nine out of ten respondents agree, but also in a similar extent to Czechs, Slovaks and Hungarians while this view is least pronounced in Austria.

Anti-EU rhetoric does not necessarily lead to the feeling that the own country is treated incorrectly by the EU institutions. In our survey only Czechs share that feeling, Slovenes and Slovaks are divided while around four out of ten Hungarians and Austrians see an unfair treatment.

In addition, the handling of migration and asylum policies casts a shadow on the EU’s image. More than 8 in 10 Czechs express their dissatisfaction, in all other countries sceptical views prevail, too. It might come as a surprise that those countries often accused of lack of solidarity by no means assess themselves this way. More than 7 in 10 Slovenians and Slovaks say that their country shows intra-EU solidarity, in the Czech Republic and Hungary about 6 in 10 share this view. Austrians are those who are most convinced of their country’s EU solidarity (nearly 9 in 10).

In all five countries, the view that there is a gap between elites and the population is overwhelming – most in Slovenia, still the weakest in Austria.

Over nine in ten respondents in all five countries value democracy and human rights as well as an independent justice system. Nearly equally high is the support for the oppositional control of the government and independent media and civil society.

At the same time, people argue for a strong leader in politics – strongest in Hungary and Slovenia, weakest in Austria – want a culturally homogenous society – strongest in Slovakia, weakest in the Czech Republic and Austria – and plead for national unity – strongest in Slovenia, weakest in Austria.

Nationalistic populism in the 5 countries – a short depiction of the state of play

Austria

The Swiss example, as a model of plebiscitary democracy to follow, is often cited to argue that also EU matters should be a subject of a direct people’s vote.

EU criticism in Austria is rather popular, giving the impression that in many areas the country would be better off solving problems on its own. The Swiss example, as a model of plebiscitary democracy to follow, is often cited to argue that EU matters should be a subject of a direct people’s vote. Nevertheless, after the Brexit vote with Austrian public opinion showing increasing support for staying in the European Union – a plus of 16 percentage points from July 2016 to December 2017[2] – claims to question EU membership were toned down and the current governmental coalition has explicitly put a break on these ideas. The same is true for the call for a stronger plebiscitary element in the political decision making process, which was postponed until 2022.

In the last two years the political discourse on EU-affairs was increasingly dominated by asylum, migration and security questions – topics also at the centre of the governmental programme as well as Austria’s EU Council Presidency. Although the current coalition agreement emphasises its pro-European orientation, the junior partner’s stance towards the EU does not appear to have remarkably changed, as it is teaming up with its Hungarian and Italian counterparts and strives to establish a strong EU-critical political group in the next European Parliament. For the time being and with the European elections around the corner, an end to the drive towards a stronger polarisation of Austria’s EU debate is not in sight.

Hungary

Instead of outright rejecting the EU for ‘promoting migration’, Prime Minister Orbán (…) offer an alternative, culturally and ethnically homogeneous vision of Christian Europe.

Hungary is often described as a laboratory case for right-wing populism: nowhere else in Europe does a populist government enjoy similar levels of power, and nowhere else does it wield such an effective propaganda machine in support of its agenda. Though politics has largely become single-issue (migration) as the FIDESZ government is fiercely against immigration and seeks to subsume all political opposition under the term “pro-migrant” (opposition parties, NGOs, EU bureaucrats, the imaginary “Soros network” etc.); the Hungarian government’s position could still be classified as moderately Eurosceptic, and not anti-European. Instead of outright rejecting the EU for “promoting migration”, Prime Minister Orbán and his government offer an alternative, culturally and ethnically homogeneous vision of Christian Europe: they talk about saving it through a return to a loose alliance of nation states and strict border control. For FIDESZ’ populism, anti-elitism is targeted against corrupt elites that are not national, but international, a mainly European. This international enemy, similarly to the threat of the EU’s “promotion of migration”, is largely constructed. Until this rhetoric remains effective, the government’s official position will not change vis-à-vis migration policy on the EU level. Nor will its Euroscepticism as every criticism from the EU can be framed as another attack from these corrupt international elites. Such developments in turn can be used for further weakening democratic institutions in the country. Due to his landslide victory in the latest parliamentary elections, PM Orbán is likely to become more active on the international scene trying to transplant his contentious ideology to other EU member states. Contradiction mainly lies in the assumption that an international alliance of nationalist populists can be lasting.

Czech Republic

Coupled with migration being de facto equated with the EU, people gladly buy into anti-EU rhetoric since it aligns well with cultural predispositions.

Our survey indicates that the Czech Republic is not only the most Eurosceptic country within our project but also amongst the most Eurosceptic countries within the entire Union, a trend that has only increased since the time of our survey, as indicated in the latest special Eurobarometer.[3] Our survey illustrates that the main culprit for this Euroscepticism is due to strong anti-migration sentiments, which has provided fertile ground for populists rallying against the EU, international conventions and liberalism in general. Coupled with migration being de facto equated with the EU, people gladly buy into anti-EU rhetoric since it aligns well with cultural predispositions.

At the time of the survey, the Czech Republic recently underwent presidential and parliamentary elections, in which migration and criticism on the EU’s handling the issue was omnipresent. The strong anti-EU, anti-migrant rhetoric, which holds immense support evident from the results of aforementioned elections, thus primarily serves to mobilise support by populist nationalist actors.

Although politicians are rarely deemed amongst the most trustworthy groups in any country, the Czech Republic takes it to another level; Youtube content creators are deemed more trustworthy than politicians amongst Czechs.[4] This exacerbates the desire for „anti-establishment” – mostly anti-EU – parties and politicians branding themselves as „not politicians.”

There are no pro-migration champions of note within the country, and pro-EU voices are marginalised. Although Prime Minister Babiš professes to be pro-European, it remains to be seen whether this is just lip service as opposed to genuine conviction, especially since his recently formed government with Social Democratic CSSD relies on support from KSCM, the communists, who are both NATO and Eurosceptic.

Slovakia

In Slovakia, the narrative of a small nation being oppressed by “stronger powers” has been in use for centuries. From Austria-Hungary, through the Soviet bloc, to Czecho-Slovakia – according to many, it was only in 1993 when Slovaks finally gained their independence. Therefore, portraying the EU as a “big power” restricting the country’s sovereignty “again”, has for many been a useful tool to gain or strengthen popularity.

…Slovakia started differentiating itself from some neighbours where the EU-bashing over sovereignty and migration crisis remained strong.

However, as such, Slovakia started differentiating itself from some neighbours where the EU-bashing over sovereignty and the migration crisis remained strong. After the 2016 parliamentary elections followed by the first Slovak EU presidency, the EU was put on a high level on the political agenda and received positive coverage by the highest political representatives, which was reflected in the public attitudes towards the EU.

As an after-effect of a political crisis starting in February 2018 due to the assassination of a journalist and his fiancée, much attention has been shifted to internal politics, pushing the EU as a topic on the sideline. Nationalistic populism remains in use primarily by far-right extremists, while nationalistic rhetoric linked to EU-bashing – such as during the migration crisis’ peak – has rather shifted towards building stronger relations with Russia and questioning of the sanctions’ regime.

Slovenia

In general Slovenians hold the EU in high esteem but think at the same time that their country is not entirely treated fairly by the EU institutions.

Slovenia only exhibits a softer version of populism. Populism should not be equated simply with anti-European attitudes. The analysis of the survey largely confirms the strong pro-European orientation of Slovenians. Nevertheless, there are certain categories of respondents that are relatively more Eurosceptic, such as those who are less educated and skilled, those living in less developed regions and rural areas. In general Slovenians hold the EU in high esteem but think at the same time that their country is not entirely treated fairly by the EU institutions. The latter could be a result of more recent events concerning bilateral issues with Croatia (e.g. the impression that the EU did not intervene actively enough in the conflict about the bay of Piran). Furthermore the financial crisis has hit Slovenia relatively harder than other countries in the region. The migrant and refugee crisis exposed Slovenia to a strong influx of refugees, which is exposed in the survey as well: the south-eastern part of Slovenia that was affected by the refugee crisis classified homogeneity and unity as important normative elements, while giving the lowest grades to the EU response on security and asylum policy. The refugee crisis in general boosted Euroscepticism on the centre-right. Brexit, the victory of Donald Trump in the US election and tensions between Eastern capitals and Brussels provided further ground for populism and nationalism, as represented by the results of the June 2018’s parliamentary elections, in which the Slovenian National Party (SNS) returned to parliament after 7 years, and the winning party with 25% of the vote was the Slovenian Democratic Party (SDS), supported by the Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán.

Why do political and societal actors resort to an “anti-European” rhetoric?

Anti-Europeanism is a natural supplement to a recent rise of nationalistic populism. An unequal distribution of wealth, fears of social decline, rural flight and challenges of globalisation are factors that make societal groups and rural regions feel detached and vulnerable to populist slogans. For many, the EU is a European model of globalisation, a softer version, but with essentially similar consequences.

Finding a scapegoat, who is to blame for all the societies’ ills is an effective populist technique. Due to a relatively low level of knowledge about the EU and its institutional set-up, it is easy to play on a populist note and portray the EU as “the other” in an “us vs. them” narrative.

Especially in times of crisis, relatively perceived instability and dynamic political developments in the region, criticism, blame and negative emotions are much easier to sell than long-term systematic solutions. The more distant people feel from decision-makers, the more inclined they are to believe that the growing disconnection of – international and national – elites translates into decisions and policies not responding to their needs. Thus, the EU, which is perceived as a separate body “somewhere” far away in Brussels, becomes a perfect target for their frustration. For populists it is therefore a tempting strategy to brand themselves as “anti-establishment” and to widen the perceived citizens-elites-gap.

Among more “traditional” parts of the society, the fear of the unknown is strongly present. The portrayal of the EU as an enemy which, by its progressiveness, threatens the traditions and cultural heritage of the country by e.g. promoting the rights of minorities and accepting asylum-seekers, helps to stir xenophobic tendencies and put populists in the position of the “defenders” of so-called “traditional values” and an imaginary common people’s will.

What should be done?

As long as the EU and a rather passive majority of its people do not take its part in the discourse – e.g. on the issue of migration, integration and the question of identity – and display proactivity, it is likely that populists will sharpen and shape the public discourse as they are actively looking for conflicts with the EU. Punishing them could worsen the situation as it only improves their argument.

The challenge of migration is used by populists as a single issue dominating the political discourse and detracting from their inability to deliver on own promises. Recent Eurobarometer data show that in the surveyed countries – Austria being an exception – trust in national governments and parliaments is lower than trust in EU institutions like the European Commission and the European Parliament.[5] More efforts should be made to highlight the advantages of EU membership, especially in rural areas and targeting lower formal educational levels. It should be made clear what would be at risk if we start a process of renationalisation. Common European solutions have much more potential to succeed in global competition. European institutions should increasingly showcase their efforts e.g. in protecting EU citizens against multinational corporations.

Increasing our efforts to empathise with different opinions within the EU would be helpful to overcome increasing cleavages and misunderstandings. Hence, enhancing cross-border exchange is of particular importance.

Our research shows that citizens hold an independent press in high esteem. The EU should therefore pay more attention to media freedom across the Union. In times of social media, especially schools are called upon to teach media literacy.

To escape the populist nationalistic dead end, we need a comprehensive pro-European agenda that takes citizens’ concerns seriously. But the constant call for direct democracy may also weaken and discredit the system of parliamentary democracy. Considering the complexity of most EU matters it is at least questionable if such broad topics shall be decided by a simple Yes or No vote. Including citizens’ views into the political decision making process via regular citizens’ and stakeholder dialogues well ahead of major decisions should be considered also by national political actors.

With the European elections around the corner it is urgent to argue why it is important to cast a vote. With populist parties on the rise, the threat of a lame European Parliament blocking common solutions and further integration is no unrealistic scenario. The coming months are key to convince citizens that this would lead to a dead end and in the long run not only damage the EU’s future but also national interests.

[1] Our research is based on five representative surveys that were conducted in all partner countries in a comparable set up in November/December 2017.

Austria: Sozialwissenschaftliche Studiengesellschaft (SWS), 16.11-5.12.2017, N=512. Czech Republic: Nielsen Admosphere, 23.-29.11.2017, N=519. Hungary: Závecz Research, 18.-22.12.2017, N=500. Slovakia: FOCUS s.r.o., 7.-13.11.2017, N=1060. Slovenia: CJMMK, 22.11.-14.12.2017, N=591 (Online).

https://oegfe.at/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Main-results-survey.pdf

[2] https://oegfe.at/2017/12/oegfe-survey-clear-majority-of-austrians-in-favour-of-eu-membership-2/

[3] https://euobserver.com/tickers/143132?fbclid=IwAR3YIVhrrWL8PZR5YhRy0DD62x0p2ZqFF7mF0lqMNTYO3ibqOFZbqMDI_p0

[4] http://www.praguemonitor.com/2017/12/19/poll-czechs-trust-politicians-less-youtubers

[5] European Commission, Standard Eurobarometer 89, March 2018. ec.europa.eu/commfrontoffice/publicopinion/index.cfm/ResultDoc/download/DocumentKy/83136

Daniel Milo is Head of Strategic Communication Programme, GLOBSEC Policy Institute, Bratislava.

Contact: daniel.milo@globsec.org

Maja Bučar is Professor at the Centre of International Relations, University of Ljubljana, Slovenia.

Contact: maja.bucar@fdv.uni-lj.si

Stefan Schaller is Research Associate and Project Manager at the Austrian Society for European Politics, Vienna.

Contact: stefan.schaller@oegfe.at

Gabriella Gőbl is Program Coordinator at the Central European University’s Center for European Neighborhood Studies (CENS), Budapest.

Contact: GoblG@ceu.edu

ISSN 2305-2635

The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Austrian Society of European Politics or the organisation for which the author works.

Citation

Hajdu, D., Lovec, M., Kvornig Lassen, C., Schmidt, P., Szalai, A. (2018). Nationalistic populism and its reception in Central Europe. Vienna. ÖGfE Policy Brief, 24’2018