Policy Recommendations

- the creation of European party lists;

- greater decision-making powers for the Parliament on issues with a clear transnational dimension;

- the allocation of more resources at member state level to educating citizens about the division of competences between the EU and its member states.

Abstract

Voter turnout in the 2019 European Parliament election increased substantially over 2014 (+8%), leading to popular commentaries of the 2019 election as the first genuinely ‘European’ contest. These facts alone, however, say nothing about whether citizens actually engaged with Europe in the run-up to election day. To shed light on this important aspect of citizen-level engagement with the EP election 2019, we ran a citizen-level survey five weeks before and immediately after EP election day, investigating the frequency and content of European themes in citizens’ political discussion. Results reveal that though the EP election campaign was successful in increasing discussion of Europe over the course of the campaign, national-level issues were nevertheless dominant in citizens’ political discussion. Moreover, in terms of content, discussion of European policy issues decreased during the campaign and, despite much elite-level discussion, we find little evidence of citizen-level engagement with debates regarding EU institutions and their potential reform.

****************************

Let’s talk about Europe!

Political discussion during the EP 2019 election campaign

Several scholars have linked an alleged EU crisis to citizens’ limited interest and knowledge of the EU and called for efforts to activate the participation of ordinary citizens in EU policy processes. The European Citizens’ Initiative (ECI) is one of the instruments that aspires to encourage citizens to participate in EU policy-making (Kandyla & Gherghina 2018).[1] These efforts originate from both a normative concern that a democracy needs well-informed citizens and from the widely held assumption that the more citizens care and know about the EU, the more likely they are to be supportive of it.

2019 was the first year that an increase in turnout was recorded, and this was dramatic: turnout was 51%, its highest level since 1999, and an increase of 8 percentage points over 2014.

For decades, scholars and commentators alike have linked to the success (or lack) of European elections in fulfilling their promise to be genuine European contests over policy-making controversies at the European level (i.e. ‘first-order’ contests) to the extent to which citizens engage in European elections, measured via the proxy of turnout. Until 2019, this has made for grim reading: since the first elections to the European Parliament were held in 1979, turnout slowly declined until 2014, from a 1979 high of 62%, to a 2014 low of 43%. 2019 was the first year that an increase in turnout was recorded, and this was dramatic: turnout was 51%, its highest level since 1999, and an increase of 8 percentage points over 2014.

This turnout spike has led to some interpretations of the 2019 European Parliament election as the first genuine European election. Given the obvious attention devoted to issues that are clearly European in scope by the media and political actors in the run-up to the election – migration, climate change and the environment, the rise of ‘populists’ as a challenge to established parties across Europe, and Brexit – it does not take a large leap of faith to reach this conclusion. However, while turnout is clearly a key indicator of engagement in an election – engagement can hardly be considered high if citizens do not vote –, it does not offer an insight into whether Europe was really salient among citizens in their everyday discussions, especially in the run-up to the elections. How much do citizens discuss Europe informally with their family, friends and colleagues? Do they care? And what do they discuss? Thus, to assess the extent to which the 2019 European Parliament elections were more first-order contests from the citizen-level perspective than in the past, it is essential to look not only at turnout, but also to understand whether Europe is a key topic for citizens and what key aspects of Europe are salient for citizens. It is perfectly possible in fact that there is a disconnect between the issues that are discussed by elite actors – both political actors and the media – and those discussed by citizens.

The survey, conducted in eight EU countries simultaneously (Austria, Denmark, Germany, France, Hungary, Italy, Poland and Spain), featured a detailed series of questions probing political discussion, and thus helps to shed light on the important aspect of how ‘European’ the 2019 EP elections were from the perspective of citizens.

To this end, as part of the Horizon 2020 RECONNECT project (‘Reconciling Europe with its Citizens through Democracy and the Rule of Law’ – https://reconnect-europe.eu/), the participating project team from the University of Vienna, together with the Austrian National Election Study (AUTNES – www.autnes.at), ran a citizen-level survey five weeks before and immediately after the 2019 European Parliament election. The survey, conducted in eight EU countries simultaneously (Austria, Denmark, Germany, France, Hungary, Italy, Poland and Spain), featured a detailed series of questions probing political discussion, and thus helps to shed light on the important aspect of how ‘European’ the 2019 EP elections were from the perspective of citizens.

A European election? An analysis of political discussion amongst citizens

Despite the European election campaign during the time period in which the survey was run, Europe itself did not become the dominant topic of conversation amongst citizens.

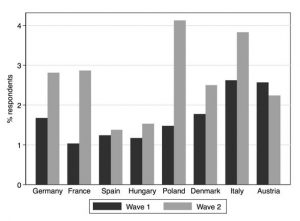

A most obvious way of measuring whether discussion of Europe was salient amongst citizens during the European Parliament election 2019 is to ask citizens what they discussed about politics. In our survey, we presented respondents with a list of 19 issues – of which two issues related to Europe, namely “European integration” and “The Euro” – and asked them to select their most discussed issue, both before the campaign began and then again immediately after the election. The results, presented in figure 1 below, do suggest that discussion of these two issues was not dominant, neither before the campaign nor by election day: before the campaign began (wave 1), these two issues combined were the most discussed issue amongst less than 2% of respondents in six of the eight countries – only in Italy and Austria did this figure slightly exceed 2%. By election day, there is only evidence of a slight increase on this rather low benchmark: around 4% of respondents in Poland and Italy named both issues as important, but in no other country of study were they most discussed by more than 3% of respondents. Thus, despite the European election campaign during the time period in which the survey was run, Europe itself did not become the dominant topic of conversation amongst citizens. Rather, citizens’ discussion focus was on policies mainly decided upon at the national level, such as climate change (10%), immigration (9.5%), health care (9.5%), pensions (6.9%), inequality in society (5.6%), environment (5.1), unemployment (4.3%), education (4.2%) or taxation (4.2%). While some of these discussion themes will certainly need European-wide decision-making (e.g., climate change and environmental policies), so far the competences to this effect are rather limited at the European level. The question arises whether citizens are aware of this.

Figure 1: Percentage of respondents mentioning the Euro or European integration as discussion topics

Note: Figure 1 is based on the survey question:

“Which issue among the following did you discuss the most in the past month? Please select one.”

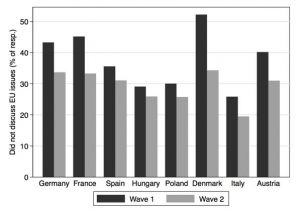

Analysis so far, however, only reveals how common it was for Europe to feature as the most discussed issue amongst citizens. Figure 2 presents the findings of an alternative approach: presenting citizens with a list of EU topics only, including a “did not discuss European politics in the last month” option, and asking them which one they have discussed the most. Results in figure 2 reveal that no discussion of EU topics occurred between slightly over 50% percent of respondents in Denmark and 25% in Italy before the EP election campaign began (wave 1), and in-between in other countries of study. The campaign did not succeed in eradicating this complete lack of discussion of EU topics amongst a sizeable number of respondents in any country of study (wave 2), as the light grey bar in figure 2 shows. Though a larger fraction did discuss an EU topic, it is worth noting that this only indicates some level of discussion and, as the findings of figure 1 suggest, discussion of EU topics amongst those who did discuss them tend to be ‘squeezed out’ by other issues.

Figure 2: Percentage of respondents do not discuss European politics

Note: Figure 2 is based on the survey question “Now, a few questions on European politics in particular. Which issue among the following did you discuss the most in the past month? Please select one answer.”

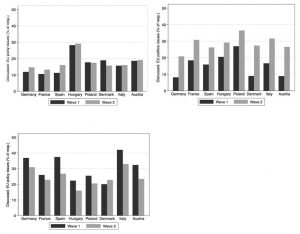

Next, we zoom in on those respondents who chose one EU-related topic. We break down the most discussed EU issues by respondents across all countries of study into the dimensions of polity, policy and politics (Schmidt 1985).[2] The former encompasses topics related to structural political aspects, such as the current future competences of the European Commission, the European Parliament and the European Court of Justice (ECJ) as well as country membership and European values and identity. The policy dimension includes regulatory aspects and policies such as those related to the EU budget, free movement of EU citizens within the EU and redistribution of refugees across EU member states. Finally, the dimension of politics refers to discussion about the topic of the EP 2019 elections. This classification allows us to pin point exactly the type of issues salient at the citizen level. Across all countries included in our study, while 33% of our respondents did not discuss EU issues at all, nearly 28% discussed policy related issues; slightly less, that is, 22% discussed politics and the remaining 17% discussed polity related issues.

Interestingly, however, policy discussion decreased during the electoral campaign in all countries expect Denmark. Thus, the campaign period lead to fewer discussions on core European policy contents but more general talk about the EP elections.

Additionally, we examine how many among those discussing EU issues, focus on each of these three aspects by country. In other words, figure 3 displays the percentages of respondents discussing politics, policy and polity aspects of the EU among those who discuss the EU. The upper right panel in figure 3 captures the polity dimension, showing that in seven countries, only 10 to 20% of political discussions on the EU were dedicated to the polity dimension – only in Hungary almost 30% of citizens discussed European values and competence distributions at the EU level. Given the fact the elite-level debate during the election campaign revolved substantially around EU institutions, its structure and reform, it is surprising to see that citizen do not engage to the same extent with the polity dimension in their discussions. Citizens rather focused discussion on the event of the election itself – thus, the politics dimension. Before the electoral campaign, among those discussing the EU, discussion pertaining to the politics dimension ranged between 8% (in Denmark) and around 35% (in Hungary). Unsurprisingly, discussion on this dimension increased substantially. In Denmark, discussions on the EP elections tripled, showing the impact European events can have on citizens. As far as discussions falling within the policy dimension are concerned, we see some variation across the eight countries. European policy discussions before the election campaign featured prominently in Italy, Germany, Spain and Austria (between 33 and 42%), while in France, Hungary, Poland and Denmark, lower numbers (between 20 and 26%) are observed. Interestingly, however, policy discussion decreased during the electoral campaign in all countries expect Denmark. Thus, the campaign period lead to fewer discussions on core European policy contents but more general talk about the EP elections (see increase in the politics dimensions).

Figure 3: Focus on politics, policy and polity aspects among those discussing the EU

Note: Figure 2 is based on the survey question “Now, a few questions on European politics in particular. Which issue among the following did you discuss the most in the past month? Please select one answer.”

Reflections and policy recommendations

The evidence gathered by RECONNECT shows that while only a minority of citizens do not discuss Europe at all during EP election times, Europe is still not salient for most citizens and their socially embedded political discussion.

In the aftermath of the 2019 European Parliament election, a key aspect highlighted by politicians and media commentators was increased turnout across all EU member states as a first sign that EP elections have become more first-order in nature. While turnout is a key indicator of democratic engagement and the nature of election, it is normatively desirable not only that citizens participate in the elections, but also that they care about the elections, debate them and perhaps even encourage others to do the same. After all, if the citizenry does not talk about the elections, the very basis of having elections in the first place may be threatened. The evidence gathered by RECONNECT shows that while only a minority of citizens do not discuss Europe at all during EP election times, Europe is still not salient for most citizens and their socially embedded political discussion. It is striking that these conclusions apply almost equally well to all countries. The extent to which this is due to features of the election campaigns themselves, overall media attention to the European Parliament elections, or a broader indifference towards the EU and its institutions in general, remains to be studied.

There is little evidence that, even by election day, citizen-level discussion reflected many core EU debates that featured in the campaign leading us to classify the EP election 2019 still as second-order contests.

Nevertheless, from a policy-making perspective, there are several observations to be put forward. There is little evidence that, even by election day, citizen-level discussion reflected many core EU debates that featured in the campaign leading us to classify the EP election 2019 still as second-order contests. In the campaign period, citizens’ discussion of European policy aspects was limited and there is little evidence of a response to the elite-level debates on structural changes to be made to the European Union and its institutions. A common discussion ground on the future of European politics is missing. Overall, the elections to the European Parliament were generally discussed without too much content on European polity and policy aspects. Parties will therefore find it difficult to fulfil their representation function in the European Parliament as citizens do not consider European policies and polity as key aspects in elections to the European Parliament.

Last but not least, citizens need to have at least a broad understanding of the competences of the EU vis-à-vis member states in order to know what is at stake in a European Parliament election and what parties and candidates can realistically promise to achieve.

These findings show that election campaigns need to focus much more on European polity and policy aspects in order to strengthen the link between the European Parliament and its citizens. To facilitate this change, a few proposals could be put forward:

- First, European party lists could be created, as national parties will have little interest in organising their electoral campaigns along European aspects.

- Second, the European Parliament needs to become more involved in decision-making processes on issues with a clear transnational dimension, such as climate change and environmental policies but also immigration and asylum rules in order to become an important player in policy areas that are of huge importance to European citizens. The new president of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen, has already announced that these highly salient issues need to be dealt with and solved in a common European endeavour – namely at the European level. The nice side effect will be that the EP will be able to fulfil its representation function at the policy level to a larger degree. In the long-term, these measures could increase the legitimacy citizens attribute to the European Parliament, and furthermore change citizens’ discussion about the European integration process substantially.

- Last but not least, citizens need to have at least a broad understanding of the competences of the EU vis-à-vis member states in order to know what is at stake in a European Parliament election and what parties and candidates can realistically promise to achieve. As education is a national competence, the most obvious solution is a willingness on the side of member states to provide young citizens with basic training on EU politics in schools as part of basic citizenship classes. Ideally, this effort would also take place in conjunction with independent and nonpartisan television programming to also provide citizens of all ages with a basic overview of how the EU works and its division of competences with member states – especially in the time period leading up to election day, when many citizens are making up their minds on how to vote. This may ultimately strengthen the fundamental mechanism of accountability that elections are expected to fulfil.

[1] Kandyla, A., & Gherghina, S. (2018). What Triggers the Intention to Use the European Citizens’ Initiative? The Role of Benefits, Values and Efficacy. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 56(6), 1223-1239.

[2] Schmidt, Manfred G. (1985) Politikwissenschaft, in Hans-Hermann Hartwich (Hrsg.) /Policy-Forschung in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland/, Springer: Berlin, S. 137-143.

ISSN 2305-2635

The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Austrian Society of European Politics or the organisation for which the authors are working.

Keywords

European Parliamament, elections, citizens

Citation

Partheymüller, J., Plescia, C., Wilhelm, J., Kritzinger, S. (2019). Let’s talk about Europe! Political dscussion during the EP 2019 election campaign. Vienna. ÖGfE Policy Brief, 19’2019