Policy Recommendations

- Understanding the links between public opinion and EU enlargement – as well as reforms in the EU more generally – is indispensable for assessing the EU integration capacity.

- Recent Eurobarometer surveys have registered an unprecedentedly high number of EU citizens in favour of new EU enlargements, suggesting that this might be the right time for decision-makers in Brussels to embark on a bold reform of EU enlargement policy in order to put this policy on a more effective and sustainable path.

- Past experiences suggest that opinions on EU enlargement, both among the general public and political elites, are quite volatile and that the current consensus over enlargement might erode rather quickly. Hence, this window of opportunity for reforms of EU enlargement policy might close soon if the opportunity is not utilised in the right way.

Abstract

Eurobarometer trends show a ‘critical juncture’ in EU enlargement policy. The long-term unfavourable trends toward the admission of new members have been reversed, with EU citizens in favour today being greater than those against. In the same fashion as the 2004 enlargement was framed through the identity argument for the purpose of reuniting Europe after the end of the Cold War, the current war in Ukraine has changed the public’s perspective towards the Balkan and Eastern Neighbourhood countries, which are recognised as ‘one of us’ by the international European community. Against this background, keeping public opinion in mind is of utmost importance, since mass attitudes, through their influence on political behaviour, do play a crucial role in influencing EU enlargement policy. Understanding the links between public opinion and enlargement – and reform in the EU more generally – is thus indispensable for assessing the EU integration capacity.

****************************

From EU ‘enlargement fatigue’ to ‘enlargement enthusiasm’?

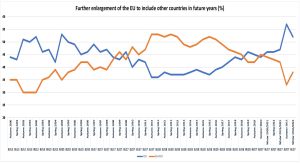

The Summer 2022 Eurobarometer registered an unprecedentedly high number of European Union (EU) citizens’ opinions in favour of a new enlargement of the Union. The graph reveals how the Russian war against Ukraine and the ensuing membership applications by Ukraine, Moldova, and Georgia have opened a ‘critical juncture’ in the EU enlargement policy. For a long time, unfavourable sentiments towards the admission of new members have dominated EU public opinion and characterised the so-called ‘enlargement fatigue’ (Devrim & Schulz, 2009).

Source: Standard Eurobarometer 54-98 (Autumn 2000 – Winter 2022/2023)

By mid-2022, 57 percent of EU citizens declared themselves to be in favour of the EU widening its membership in the future, while only 33 percent of the respondents were against it. This score represents a historical high with no precedent within this Eurobarometer series, which was initiated in 2000 during EU accession negotiations with Central and Eastern European countries (that were to become members in 2004 and 2007). Hence, the return of greater public support for enlargement may perhaps mark the end of enlargement fatigue and the beginning of a new positive momentum for this policy.

By mid-2022, 57 percent of EU citizens declared themselves to be in favour of the EU widening its membership in the future, while only 33 percent of the respondents were against it.

At the same time, these new trends should be handled with extreme caution. When examining the evolution of EU enlargement fatigue, positive attitudes towards new enlargements seem to erode over time, and no fast-track accession policy is in sight. Moreover, the inversion of trends in EU public opinion started well before the Russian military aggression. Supporters of enlargement have gradually increased while opponents have decreased since the second half of 2016, in the aftermath of the Brexit referendum, so attitudes towards EU enlargement seem to be linked to the rise and fall of Euroscepticism and overall trust in EU integration more generally.

Additionally, recent experience shows how elites and political parties retain an important role in affecting volatile and sensitive mass attitudes towards EU enlargement policy. Finally, in reaction to rising enlargement fatigue and Euroscepticism, today’s EU enlargement policy is run on an even stronger intergovernmental basis than in the past. Thus, member states’ veto power maintains the risk of this policy being hijacked by individuals’ public opinion and national political agendas, which in some countries remain quite sceptical towards new EU accession.

Understanding the links between public opinion and enlargement – and reforms in the European Union more generally – is thus indispensable for assessing the EU integration capacity.

Keeping public opinion in mind is of utmost importance, since mass attitudes, through their influence on political behaviour, do play a crucial role in outlining the EU enlargement policy. Understanding the links between public opinion and enlargement – and reforms in the European Union more generally – is thus indispensable for assessing the EU integration capacity.

From permissive consensus to enlargement fatigue and resistance

EU enlargements were, for a long time, largely ignored by European public opinion. This lack of interest might have been caused by little knowledge among Europeans about EC/EU policymaking in general and enlargement policy in particular, as well as a lack of understanding of the significance of the latter for the future of the EU as a political system. At the same time, EU citizens have been marginally involved in public discussions about enlargement, while the admission of new members has never been subject to referenda in the EU member states – something that might have reduced public interest in the issue in comparison to other themes connected with EU integration and directly subjected to national campaigns.

Most EU citizens also believed that granting EU membership to new countries was ‘historically and geographically natural and, therefore, justified’ (Eurobarometer 61, Spring 2004).

When looking at the EU enlargement in 2004, public attitudes seemed to have still been characterised by the so-called ‘permissive consensus’ (Hooghe & Marks, 2009). Scholars agree that a sceptical but accommodating public opinion has accompanied the 2004 accessions, allowing political elites to conclude intergovernmental negotiations despite low interest and little public salience of the topic (Timuş, 2006). Indeed, for a majority of EU citizens, it appeared economically irrational to support the 2004 enlargement, contrary to the enlargement towards the European Free Trade Association countries in 1995, which broadly seemed rational as it relates to net-payer countries (Toshkov et al., 2014). However, most EU voters remained mildly in favour of the 2004 enlargement, mainly on the basis of identity reasons and a shared sense of belonging (Schimmelfennig & Sedelmeier, 2002). These countries were perceived as part of the pan-European identity, sharing a distinct cultural civilization with its own history, tradition, and religion (Maier & Rittberger, 2008). Indeed, most EU citizens believed that enlargement should be implemented due to various significant non-economic reasons, including the increase of Europe’s role in the world, the moral duty to reunite Europe after the end of the Cold War, and the reduction of armed conflicts (Timuş, 2006). Most EU citizens also believed that granting EU membership to new countries was ‘historically and geographically natural and, therefore, justified’ (Eurobarometer 61, Spring 2004).

After the 2005 referenda and the completion of the fifth enlargement round, an official EU discussion on the future of enlargement policy was triggered.

However, this situation soon started to change and mutate into what has come to be known as ‘enlargement fatigue’, a lack of enthusiasm and/or confidence in the overall enlargement project (Devrim & Schulz, 2009). The turning point was probably created by the European Constitution debate, specifically the 2005 referenda in France and the Netherlands and their rejection of the new EU constitutional treaty (Walldén, 2017). In these campaigns, despite the efforts of pro-European elites to separate the enlargement issues from the question of the ratification of the ‘Treaty establishing a Constitution for Europe’, complaints for previous enlargements (toward Central-Eastern Europe) and preoccupations for new ones (Bulgaria, Romania, and Turkey in particular) prevailed in the public debate, and opposition to EU widening was a key feature of Eurosceptic propaganda. It was the outcome of the 2005 referenda that prompted member states to engage in a formal debate on revising EU enlargement policy. After the 2005 referenda and the completion of the fifth enlargement round, an official EU discussion on the future of enlargement policy was triggered.

Then, Euroscepticism and diffidence towards new enlargements kept growing due to discontent regarding the level of preparation in Bulgaria and Romania during their accession to the EU in 2007.

Thus, post-2004 enlargement reflections reveal a rising opposition and declining level of support among EU citizens for new EU enlargement, eroding permissive consent and shifting public opinion towards a ‘binding dissensus’ (Toshkov et al., 2014). In particular, increasing workforce immigration, lower tax rates, and lower wages brought into the EU by the new member states, combined with rising levels of unemployment in the old EU states, provoked public dissatisfaction and opposition to this policy (Timuş, 2006). Then, Euroscepticism and diffidence towards new enlargements kept growing due to discontent regarding the level of preparation in Bulgaria and Romania during their accession to the EU in 2007. As such, member states did not perceive enlargement as a win-win situation, as they believed it merely benefits new members while providing little if any profit to the old ones (Devrim & Schulz, 2009). As a result, enlargement started to be perceived by many as a vehicle for importing institutional instability into the EU, thus also posing the question of EU absorption capacity (Devrim & Schulz, 2009). Indeed, the Union’s functioning has been complicated by a cumbersome decision-making process that can seriously jeopardise the ability of its institutions to function and the efficiency of its decision-making processes. Enlargement also unveiled the growing gap between political elites and the public stemming from the EU’s institutional architecture, which permits little input from the member states’ citizens.

Overall, these modifications put renewed emphasis on EU absorption capacity, posing intermediate benchmarks to be fulfilled by candidate countries and increasing member states’ grip over the process (Miščević and Mrak 2017).

Yet, during this period, some important political objectives were still achieved on the basis of a ‘renewed consensus on enlargement’ (Council of the EU 2006), which paved the way to the EU accession of Croatia (in 2013), as well as to the opening of accession negotiations with Montenegro (in 2011) and Serbia (in 2013). Confronted with growing Euroscepticism, EU leaders decided to make the enlargement process more demanding and to increase member states’ control over it on the basis of the ‘three Cs’ principles, expressed by the 2006 renewed consensus: geographical consolidation, stricter conditionality, and improved communication. This has led to what has been described as the ‘creeping renationalisation’ of this policy (Hillion, 2010), a trend that was further reinforced by the European Commission in the context of accession negotiations with Croatia, Montenegro, and Serbia. In 2012, the European Commission formalised these changes by introducing the ‘fundamentals first’ approach in its enlargement strategy (European Commission 2012) in order to address core issues – the rule of law, fundamental rights, and democratic institutions – from an early stage in the negotiations. Overall, these modifications put renewed emphasis on EU absorption capacity, posing intermediate benchmarks to be fulfilled by candidate countries and increasing member states’ grip over the process (Miščević & Mrak, 2017). Eventually, these changes had a profound impact on the nature of the accession negotiation talks between the EU and the Western Balkans, which were carried out through a much more intergovernmental logic (Balfour & Stratulat, 2015).

Behind the declared goal of better preparing for accession, the mutation of enlargement policy unambiguously reflects enlargement fatigue and the rise of Euroscepticism in the EU itself. While it is true that most of the aspirant countries do not meet all the Copenhagen accession criteria – and there has even been some backsliding – the member states’ adverse sentiment towards enlargement is partially to blame, thus creating a vicious circle. At the same time, this stricter EU conditionality did not succeed in strengthening support for EU accession among the European population, and large segments of EU citizens remained against this policy even in 2012, when Croatia concluded accession negotiations and was accepted to become a member the following year, mainly due to its strong ties with Austria and Germany (Toshkov et al., 2014).

Behind the declared goal of better preparing for accession, the mutation of enlargement policy unambiguously reflects enlargement fatigue and the rise of Euroscepticism in the EU itself.

The final blow to support for EU enlargement policy came, however, when the EU entered a series of multiple existential crises that have dominated the European scene in recent years: the eurozone crisis, the refugee crisis, Brexit, and the rise of Eurosceptic and far-right forces and programmes across the continent (Walldén, 2017). All these factors have had a direct or indirect negative effect on the prospect of further enlargements and fueled scepticism about the admission of new members in several European capitals. This new situation was first certified in 2014 by the keynote speech at the European Parliament of the then–new President of the European Commission, Jean-Claude Juncker, which seemed to many observers to have suspended the enlargement process (Juncker, 2014).[1]

Under these new conditions, EU enlargement was increasingly hijacked by individual vetoes and national agendas.

Since then, there has been a transformation of EU enlargement’s narrative from fatigue into ‘resistance’ (Economides, 2020) and a mutation of the renewed consensus on enlargement into an open dissensus and contestation. Under these new conditions, EU enlargement was increasingly hijacked by individual vetoes and national agendas. This situation was particularly evident in the European Council’s behaviour, which has repeatedly failed to agree on opening accession negotiations with Albania and North Macedonia (and to provide visa liberalisation to Kosovo), despite the remarkable progress of these countries in meeting EU demands.

Moreover, it is interesting to note the different roles played by EU political elites in this new phase, when constraints to enlargement started to be exerted by the political elites themselves. During this new phase, no one would have expected EU leaders to seize initiatives on enlargement when the EU itself is under threat, with the euro at risk, Brexit, the inflows of refugees unsettling the European political arena, and far-right Eurosceptic parties surging. This shift in political elites’ attitudes has also been confirmed by a recent study on parliamentary debates on EU enlargement in eight member states (Economides et al., 2023). The analysis clearly shows the decreasing salience and increasing aversion towards new accession within national parliaments. At the same time, the article shows the key role of challenger parties (from both the radical left and radical right) in constraining mainstream political parties with more negative views on enlargement.

From fatigue to enthusiasm?

The return of war in Europe and the ensuing membership applications by Ukraine, Moldova, Georgia, and Kosovo represent dramatic turning points in recent European history, which has put the spotlight on EU enlargement policy as a key tool to pursue peace, democracy, and prosperity across Europe. The fact that the European political elites affirmatively replied to third countries’ demands for integration proves a positive momentum and new dynamism in this policy. Indeed, the European Council almost immediately granted candidate status to Ukraine and Moldova in June 2022 and opened accession perspectives for Georgia. Soon after, it also opened accession negotiations with Albania and North Macedonia and then gave EU candidate status to Bosnia and Herzegovina in December 2022.

The fact that the European political elites affirmatively replied to third countries’ demands for integration proves a positive momentum and new dynamism in this policy.

Moreover, the change in the Eurobarometer trend in summer 2022 confirms this ‘critical juncture’ in enlargement policy. In fact, the long-term unfavourable trend toward the admission of new members has reversed, with public opinion in favour being greater than against. In the same fashion as the 2004 enlargement was framed through the identity argument for the purpose of reuniting Europe after the end of the Cold War, the current war in Ukraine has changed the public’s perspective towards the Balkan and Eastern European countries, which are recognised as ‘one of us’ by the international European community – or at least as having a common ‘enemy’.

Against this background, the central issue is, however, not simply to establish for how long this momentum could last. The crucial question here is about what type of enlargement policy might come out of war and which characteristics it ought to have in order to overcome the significant shortcomings that emerged in the EU accession of the Western Balkans so far, which have been on the path from post-conflict reconstruction to EU membership already for more than 20 years. In other terms, the crucial issue now for the ‘European bureaucracy’ is to provide concrete proposals to convert this consensus among the general public and political elites into concrete policies that will prove more effective, suitable, and sustainable than those in the past.

****************************

****************************

[1] Presenting the new European Commission priorities to the European Parliament, Juncker declared that no further enlargements would take place during its mandate. Whereas Juncker statement was factually correct, the political message emerging from the European Commission’s proprieties was devastating for EU enlargement policy, which was relegated to the extreme margins of the EU agenda. At the same time, the new Commission abolished the Commissioner/DG for EU enlargement, creating the European Commissioner/DG for European Neighbourhood and Enlargement Negotiations (DG NEAR) instead.

Balfour, R. & Stratulat, C. (Eds.). (2015). EU member states and enlargement towards the Balkans. European Policy Centre Issue Paper no. 79, July.

Council of the European Union (1997). Conclusions of the General Affairs Council of 29 April, Brussels. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/PRES_97_129

Devrim, D. & Schulz, E. (2009). Enlargement Fatigue in the European Union: From Enlargement to Many Unions. Real Instituto Elcano. https://www.realinstitutoelcano.org/en/work-document/enlargement-fatigue-in-the-european-union-from-enlargement-to-many-unions-wp/

Economides, S. (2020). From Fatigue to Resistance: EU Enlargement and the Western Balkans. Dahrendorf Forum IV. Working Paper No. 17.

Economides, S., Featherstone, K. & Hunter, T. (2023). The Changing Discourses of EU Enlargement: A Longitudinal Analysis of National Parliamentary Debates. Journal of Common Market Study Early View. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.13484

European Commission. (2012). Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions: Enlargement strategy and main challenges 2012–3. COM (2012) 600 final.

Hillion, C. (2010), The Creeping Nationalisation of the EU Enlargement Policy. Swedish Institute for European Policy Studies (SIEPS).

Hooghe, L. & Marks, G. (2009). A Postfunctionalist Theory of European Integration: From Permissive Consensus to Constraining Dissensus. British Journal of Political Science. 39(1). 1-23. doi:10.1017/S0007123408000409.

Juncker, J. C. (2014). A New Start for Europe: My Agenda for Jobs, Growth, Fairness and Democratic Change. Political Guidelines for the next European Commission, Opening Statement in the European Parliament Plenary Session, Strasbourg, 15 July 2014.

Maier, J. & Rittberger, B. (2008). Shifting Europe’s Boundaries: Mass Media, Public Opinion and the Enlargement of the EU.’European Union Politics, 9(2): 243–267. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/1465116508089087

Miščević, T. & Mrak, M. (2017), The EU accession process: Western Balkans vs. EU-10. Croatian Political Science Review. 54(4):185–204.

Schimmelfennig, F. & Sedelmeier, U. (2002). Theorizing EU enlargement: research focus, hypotheses, and the state of research. Journal of European Public Policy. 9(4), pp. 500–528. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/epdf/10.1080/13501760210152411?needAccess=true&role=button

Timuş, N. (2006). The role of public opinion in European Union policy making: The case of European Union enlargement. Perspectives on European Politics and Society. 7(3). pp. 336-347. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/15705850601056470

Toshkov, D., Kortenska, E., Dimitrova, A. & Fagan, A. (2014). The ‘Old’ and the ‘New’ Europeans: Analyses of Public Opinion on EU Enlargement in Review. MAXCAP. https://userpage.fu-berlin.de/kfgeu/maxcap/system/files/maxcap_wp_02.pdf

About the article

ISSN 2305-2635

The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Austrian Society of European Politics or the organisation for which the authors are working.

Keywords

European Union, enlargement, Euroscepticism, public opinion, fatigue, enthusiasm

Citation

Bonomi, M., Rusconi, I. (2023). From EU ‘enlargement fatigue’ to ‘enlargement enthusiasm’? Vienna. ÖGfE Policy Brief, 19’2023