Policy Recommendations

- Every change affecting the Western Balkan reforms and convergence dynamics towards the EU must be designed by taking into account the “space”, meaning territory, the local institutions that have the capacity to implement the reform forward, and the people.

- The enlargement dynamics and in-built connectivity with the EU provide the rails along which Western Balkan countries will develop. However, in an ever-changing world, we must be aware of competing models of development that interact with each node of the Western Balkans triangle (space, institutions, and people).

- People (civil society organisations, small and medium-sized enterprises, academia, or other interest groups) have to be at the centre of all policies in order to ensure democratic institutions.

Abstract

There is a gap between the six countries of the Western Balkans (WB6) and their partners in the European Union (EU) in human capital, the quality of its infrastructure, the structure of the economy, and the quality of local institutions, factors that condition the WB6 growth rate. The speed of WB6 convergence towards the EU defines the pace of enlargement progress.

All WB6 countries are fully engaged in progressing in the main reform areas that are transforming their institutions, developing their economies, and improving the quality of life of their citizens, and the European Union, through its enlargement mechanism and funding, is supporting them to make these necessary advancements. But on their way to membership, WB6 economies must grow quickly to catch up with their EU peers, and local infrastructure must be upgraded and extended.

This Policy Brief creates a methodological framework that links the local infrastructure, domestic institutions, and people, allowing us to understand the dynamics and complexity of sustainable and resilient development paths as well as identify entry points for the WB6 and EU policy-makers.

****************************

Convergence of the Western Balkans towards the EU: from enlargement to cohesion

The main impediments to growth in the six countries of the Western Balkans (WB6) as defined by international financial institutions and other organisations, are the endowment of the region in human capital, the quality of its infrastructure, the structure of the economy, and the quality of local institutions.[1] The size of the gap between the Western Balkans (WB) and their partners in the European Union (EU) in each of the above-mentioned factors determine the WB6 growth rate (and the growth differential) between the two blocs. The speed of WB6 convergence towards the EU defines the pace of enlargement progress.

WB6 citizens should enjoy employment, good health services, education, and social services and must keep their institutions accountable.

All WB6 countries are engaged in reforms that are transforming their institutions, developing their economies, and improving the quality of life of their citizens. The EU, through its enlargement mechanism, is supporting them. But on their way to membership, WB6 economies must grow quickly to catch up with their EU peers, and local infrastructure must be upgraded and extended. Domestic institutions should complete the reforms and also deliver on the rule of law, justice reform, the fight against corruption and organised crime, as well as security and fundamental rights. WB6 citizens should enjoy employment, good health services, education, and social services and must keep their institutions accountable.

But can all this be done at the same time? Can we have privileged entry points for policy-makers? Who are the good actors for change? What should the mechanisms of change be? What are the pitfalls to be avoided? How do we make the outcomes irreversible?

Interconnectedness of “space”, people, and institutions

The COVID-19 shock provided a life-test of the resilience of the WB6 development model. During the pandemic, it became evident that to make available to their population the needed medical equipment and supplies, WB6 national institutions were forced to closely and quickly coordinate with each other. To contain the spread of the virus and respect quarantine measures, citizens had to respect the decisions of their governments. To be respected, such decisions needed to be perceived as legitimate (i.e., as protecting the interests of citizens and as being the best available options under the circumstances).

People are a key element in ensuring democratic institutions and, subsequently, democratic countries.

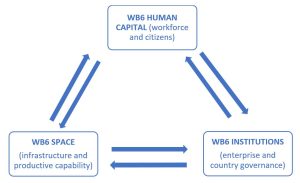

Thus, while studying the interaction between connectivity and the development of a territory, three systemic elements appear. First is the “space”, as defined by the endowment of the territory in production capability and in connective infrastructure (transport, energy, and data). Second are the local “institutions”, which, in a simplified definition, would be the “structures and mechanisms of social order and cooperation governing the behaviour of a set of individuals” materialised in the array of both public and privately owned organisations. The way domestic institutions are set up, function, and deliver defines the efficiency of policy-making and increases or hampers any endowment that a country has in infrastructure or production capability. The third element is the local “people”. As workforce, they are a key factor in growth, while as citizens, they keep local institutions accountable, efficient, and democratic. People are a key element in ensuring democratic institutions and, subsequently, democratic countries.

Those three elements can be represented in a triangle where the nodes of space, people, and institutions permanently interact with and impact each other. Once the WB is seen as an integral part of a system, the interconnectedness between roads, global value chains, institutional good governance, and levels of education becomes evident.

The challenge for policy-makers is to identify actions that induce a “Pareto improvement”[2] in the space-institutions-people system in the long term: i.e., a positive improvement in one node without negatively impacting the rest of the triangle. To be realistic, the impact assessment of any intervention should include the three nodes, even if the planned action happens only in one of them. For the change to be durable, we need to factor in the induced change, resilience, and sustainability in each node and, at the same time, the resilience of the whole triangle.

To be realistic, the impact assessment of any intervention should include the three nodes, even if the planned action happens only in one of them.

Contribution of enlargement

While permanently linked with each other, each node is in contact with and interacts with other triangles. In a highly globalised world, interaction with the exterior is one of the most common ways of inducing change in a selected triangle, be it in space, human resources, or institutions. Below, we present some illustrative cases of how different WB6 nodes interact with selected third actors. The selected examples are not representative and serve only didactic purposes.

The WB6 countries are committed to their EU membership, and the EU is currently the only third actor that, through the enlargement process, has an official permanent linking mechanism with all three nodes of the WB6 triangle. In the following Policy Brief , we will stay at the EU level and not focus on the interaction of WB6 countries with specific EU member states,[3] EU regions[4] or other EU-linked actors such as big companies or international finance institutions.

In the space node, two examples illustrate the systemic connections with the EU: the extension of the EU Trans-European Transport and Energy Networks in the WB6 and the participation of the WB6 economy in EU value chains. By design, the “WB6 Connectivity Agenda” is an “indicative extension” of the EU’s,[5] while the Peninsula’s economy is de-facto part of the EU’s. In 2017, the WB6 had “73% of their total goods trade with the EU within an almost completely liberalized trade regime. Between 75-90% of their banking systems are foreign-owned (mainly by German, Italian, French, Austrian and Greek banks)”.[6]

In support of a speedier convergence, the European Commission has adopted an Economic and Investment Plan (EIP) worth €9 billion in grants (and up to €20 billion in loans). EIP also contains a list of 10 flagship projects designed to cover the main sectors and all the WB6 countries.

To better channel EU aid in the region, different proposals include the reinstatement of an EU Agency for Reconstruction and Development in the WB6 region, the establishment of a joint regional Western Balkan Investment Committee equipped with supra-national powers, or the set-up of a regional Western Balkan Regional Infrastructure Fund.[7]

The next target of EU intervention in WB6 is the capacity-building of public institutions.

However, EU institution-building actions do not deliver the intended outcomes because domestic South-East European state institutions have poor governance quality, are captured, or their leaders lack the political will for reform. “Funds from the EU’s Instrument for Pre-accession Assistance range from around 40 million euro a year for Montenegro to 200 million euro for Serbia and are directed almost entirely to supporting administrative and other institutional reforms without sufficiently taking account of the enormous development gap between the Western Balkans and the EU.”[8] The EU-supported public administration reforms have only partially addressed elements of institutional good governance, mostly focusing on capacity-building projects that assist them in improving their deliverables (or on output legitimacy elements).

Further, we estimate that the role of European enterprises as vectors of change capable of improving WB6 corporate management practises and governance models has not been fully utilised. EU companies are key to the development of WB6 productive capacities, the inclusion of the peninsula in the European global value chains[9] and the adoption of new technologies. Innovative supporting schemes should be devised and adopted to encourage EU companies to be more active in the WB6, beyond market access. Given the embeddedness of the WB6 economy in that of the EU, Union industrial policy should contain at least a chapter on the WB6, and adapted policy measures should be foreseen and budgeted.

Innovative supporting schemes should be devised and adopted to encourage EU companies to be more active in the WB6, beyond market access.

Until now, EU infrastructure support has been designed separately from WB6 institutional reforms. The dependency of implementation of the Connectivity Agenda on the quality of WB6 institutions, on their legitimacy and good governance mechanisms, as well as the infrastructure’s own impact on local institutions, has not been strategically assessed.[10] International finance institutions (IFIs) do not vet the good governance mechanisms, skills, or competences of WB6 public institutions in charge of infrastructure before allocating EU grants or approving loans. On the other side, the contribution of domestic non-state actors – civil society organisations, small and medium-sized enterprises, academia, or other interest groups – has been limited to their consultative and “watchdog” roles.

With regard to the people node, a very visible interaction in EU-WB6 is between education and emigration. In education, there are different European programmes available for WB6 students and researchers, such as Erasmus+ or Horizon 2020. Regarding emigration, on the positive side, emigrating to the EU allows WB6 citizens to realise their life aspirations and, through remittances, contributes to the WB6 balance of payments. On the negative side, it deprives WB6 economies of their best and most productive elements and society of its middle class, i.e., the most educated and engaged citizens.

With regard to the people node, a very visible interaction in EU-WB6 is between education and emigration.

In enlargement, the EU uses the intergovernmental model of interacting with the WB6 countries. This explains the preponderant role of the institution node in EU-WB6 interactions, and especially of state institutions. But when domestic state institutions are captured or are incompetent, they distort all the intended EU impact in the WB6 triangle.

The EU is a systemic actor supporting the WB6 in its reforms and development path. It supports the WB6 in space, in people, or in institutions (through institution building), but those interventions are not comprehensively aligned with the EU’s own growth policies or interconnected amongst themselves.

When domestic state institutions are captured or are incompetent, they distort all the intended EU impact in the WB6 triangle.

Conclusion

By putting space, people, and institutions in one system, we have tried to present all these challenges in one plan, underline their interconnectedness and complexity, and provide elements of reflection useful for policy-makers. By looking at it as one system, we have drawn some preliminary conclusions.

First, to be virtuous and resilient, any change affecting the WB6 reforms and convergence dynamics towards the EU must be designed by taking into account all three nodes of the triangle. The resulting policies should be spread out from a long-term perspective and include sustainability and resilience factors on top of efficiency.

Second, the enlargement dynamics and in-built connectivity with the EU provide the rails along which WB6 countries will develop. However, in an ever-changing and hyper-connected world, we must be aware of competing models of development that interact with each node of our WB6 triangle.

Finally, this is, of course, only a modest first step in adopting a comprehensive development approach adapted to the very specific WB6 situation. As such, its goal is to set up some – useful – reference points that can hopefully serve to initiate a broad and inclusive reflection on the development of this part of Europe in the years to come.

****************************

Photo: Gerd Altmann / Pixabay

****************************

[1] For instance, see: Ilahi, N. et al., Lifting Growth in the Western Balkans, IMF 2019. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/Departmental-Papers-Policy-Papers/Issues/2019/11/11/Lifting-Growth-in-the-Western-Balkans-The-Role-of-Global-Value-Chains-and-Services-Exports-46860

Sanfey, P. et al., How the Western Balkans can catch up, EBRD 2016. https://www.ebrd.com/news/2016/how-the-western-balkans-can-catch-up.html

Government at a Glance – Western Balkans, OECD 2020. https://www.oecd.org/fr/gov/government-at-a-glance-western-balkans-a8c72f1b-en.htm

An Economic and Investment Plan for the Western Balkans, European Commission 2020. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_20_1811

Sanfey, P. et al., How the Western Balkans can catch up, EBRD 2016. Government at a Glance – Western Balkans, OECD 2020. An Economic and Investment Plan for the Western Balkans, European Commission 2020.

[2] A Pareto improvement occurs under the rubric of neoclassical economic theory when a change in distribution harms no one and helps at least one person, given the initial allocation of goods for a set of persons. The theory suggests that improvements to Pareto will continue to enhance an economy’s value until it achieves a Pareto equilibrium, where improvements to Pareto are no longer possible. For further information, see: https://cleartax.in/g/terms/pareto-improvement

[3] See some useful literature on connectivity between a member state and an WB6 country: Armakolas, I. et al., Broadening Multilevel Connectivity Between Greece and North Macedonia in the Post-Prespa Environment, ELIAMEP. https://www.eliamep.gr/en/publication/διευρύνοντας-την-πολυεπίπεδη-διασυν/

Bergantino, A. et al., The Adriatic Beltway: Transport Connectivity in Adriatic Area. https://sagov.italy-albania-montenegro.eu/sites/sagov.italy-albania-montenegro.eu/files/2020-09/Transport%20Connectivity%20in%20South%20Adriatic%20Area_The%20Adriatic%20Beltway_2020.pdf

[4] For an overview of connectivity in the space node between the WB6 and EU regions as applied to the maritime dimension, WB South Adriatic Connectivity Governance (SAGOV). See: https://connectivity.cdinstitute.eu

[5] International relations – Western Balkans, Mobility and Transport, European Commission: https://ec.europa.eu/transport/themes/international/enlargement/westernbalkans_en

[6] Bonomi, M., Reljić, D., The EU and the Western Balkans: So Near and Yet So Far, SWP Comments 53, December 2017. https://www.swp-berlin.org/publications/products/comments/2017C53_rlc_Bonomi.pdf

[7] Grieveson, R., Holzner, M., Investment in the Western Balkans. New Directions and Financial Constraints in Infrastructure Investment, wiiw, November 2018. https://wiiw.ac.at/investment-in-the-western-balkans-dlp-4705.pdf

[8] The EU and the Western Balkans: So Near and Yet So Far, op cit.

[9] To stay competitive, enterprises increasingly organise their production globally, breaking up their value chains into smaller parts supplied by a growing number of providers located worldwide. International sourcing of business functions is a key feature of global value chains (GVCs) as European businesses increasingly globalise their production processes. For further information, for instance, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Global_value_chain

[10] For more details on interaction between Connectivity Agenda and governance, see: Hackaj, A., Hackaj, K., Berlin Process: Implementation of Connectivity and Institutional Governance, CDI, March 2019. https://www.connectwitheu.al/wp-content/uploads/bsk-pdf-manager/2019/07/CDI_Berlin-Process_April2019.pdf

About the article

ISSN 2305-2635

The views expressed in this publication are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Austrian Society of European Politics or the organisation for which the author is working.

Keywords

Berlin Process, Connectivity Agenda, European Union, Institutional Governance, Democracy, Western Balkans

Citation

Hackaj, A. (2023). Convergence of the Western Balkans towards the EU: from enlargement to cohesion. Vienna. ÖGfE Policy Brief, 18’2023