Policy Recommendations

- A joint European operational security strategy should be established to counter Eurosceptic and Europhobic arguments in the Western Balkans and foster the rule of law in the region.

- In the area of security EU member states should provide candidate and potential candidate countries technical cooperation, including equipment donations, strategic advice and training in order to promote the transfer of know-how, consolidate networks of trust with partner services, while enhancing the values inherent in European integration and bilateral relations.

- A more fluid flow and exchange of information would be the necessary basis for further bilateral and multilateral funding.

Abstract

Security, trafficking and the rule of law are major concerns for all European actors, whether private or public, EU member states, candidate countries or potential candidate countries. In fact, it would be a mistake to consider the Western Balkans as a periphery of the European Union (EU) and on the margins of the decision-making process. According to Angela Merkel during her visit in Belgrade on 13 September 2021: “We, who are already members of the European Union, should keep in mind that there is an absolute geostrategic interest for us to include these countries in the European Union.”

As stated by the European Policy Centre in a discussion paper about the Conference on the Future of Europe, “Allowing the Balkan countries to witness and contribute to this initiative could foster a sense of togetherness and partnership that has been lacking from the long, drawn-out formal accession process” (Stratulat, Lazarević 2020). This is true for economic matters as well as for security issues, joint actions and existing common initiatives that are carried out. Yet, for the moment, already existing structures and cooperation seem insufficiently promoted to the general public and need to be reinforced.

The security rhetoric that is flourishing within Europe and beyond its borders pushes states to turn less towards and to welcome less migrants. The subject has become the flagship of populist speeches that use it as a justification for their attacks on the rule of law. This counter-productive dynamic must be combated by increased cooperation between the competent services and the demonstration of success stories. Moreover, the purpose of working closer together on these issues remains, with a view to building a common security, to properly prepare the EU accession of the Western Balkan countries. This is what is at stake in this reflection, between observation, awareness and proposals for action.

* The authors started writing the Policy Brief in June 2021, the final corrections are from December 2021.

****************************

Considering EU enlargement through the prism of security cooperation

Introduction

“Today, there is an aspiration for a more united and more sovereign Europe that must be met; for a Europe that asserts itself as a citizen space of shared cultures, where an identity rich in diversity but based on common principles and values develops; for a Europe that exploits all the potential of economic recovery and of the ecological and digital transition.”

Clément Beaune, French Secretary of State to the Minister of Europe and Foreign Affairs, in charge of European Affairs, 4 November 2020

Without directly mentioning it, this Communication on the French Presidency of the Council of the European Union refers to the malaise that has persisted since 2004, the year of the so-called ‘great enlargement’ of the European Union (EU). Seventeen years ago, ten candidate countries, mostly from Central and Eastern Europe, joined the EU and two more countries from Eastern Europe followed in 2007. These enlargement rounds lead to a significant extension of the territory covered by the law of the EU from 15 to 27 member states, after several years of negotiations which appeared – particularly in France – based mainly on economic considerations.

The post-1989 geopolitical recomposition took place within a European framework, responding to a ‘demand of Europe’ and integration into its economic and political model. The democratic transition in the post-Soviet countries should allow for the installation of a Western-style political normality, with a functional political system and consensual programmes around European integration.

Once again, these Eurosceptic populist waves with authoritarian tendencies can be observed in Western Europe as well, that’s why it is essential to foster cooperation going further simple ministry notes.

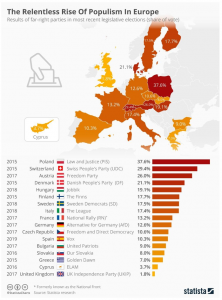

However, these state constructions, sometimes very recent, have differences with their Western counterparts. The institutional apparatuses appear to be less adapted and structured; moreover, they are partly established on a background of clientelism and corrupt behaviours but the Eastern states are not the only ones to be affected, these facts do not spare their Western neighbours. In addition, to these considerations, there is the rise of populist and national-populist Eurosceptic parties in some of the countries, as shown in the image below. They are taking over the leadership of the executive, have a majority in parliamentary assemblies, and are reshaping laws and constitutions, quite virulently in Central and Eastern Europe. Once again, these Eurosceptic populist waves with authoritarian tendencies can be observed in Western Europe as well, that’s why it is essential to foster cooperation going further simple ministry notes.

The driving force behind the political discourse of these Eurosceptic, or even Europhobic, currents is the ‘lack of security’ on the continent.

These waves are also increasingly making their mark on the daily life of the European Parliament. This phenomenon generates functional problems within the institutions, as illustrated recently by the blockages of the Post COVID-19 Recovery Plan or the adoption of the 2021-2027 European budget by the Polish-Hungarian duo. The capacity of this Eurosceptic ‘fortress’ to entrench the parliamentary proceedings weakens the European structures and maintains numerous misunderstandings with the candidate countries.

The driving force behind the political discourse of these Eurosceptic, or even Europhobic, currents is the ”lack of security” on the continent. In the public opinion of the older EU member states, the 2004 and 2007 enlargements were often perceived as a problem in terms of intra EU migration and trafficking, with uncontrolled flows of refugees intensifying since 2015, endangering the security of national territories. The geographical location of the Western Balkans is exposed as an expansion of the geographical borders of the EU and raises the problem of the surveillance of its perimeter.

However, it is clear that joint actions are being taken to put in place an operational security strategy based on the cooperation of the competent services. In 2007, with the accession of Bulgaria and Romania, a ”cooperation and verification mechanism” was set up in order to evaluate the progress made in the field of justice, the fight against organised crime and corruption. After the accession of Croatia on 1 July 2013, these issues emerged in the framework of the EU enlargement strategy until it was endorsed in the Sofia Declaration of 17 May 2018, following the EU-Western Balkans Summit of the Bulgarian Presidency of the Council of the European Union.

The authors of this Policy Brief seriously hope the French Presidency of the Council of the European Union will pay sufficient attention to the Western Balkans.

Thus, in order to counter the Eurosceptic and Europhobic arguments, while accompanying the candidate and potential candidate countries towards a better guarantee of the rule of law and a successful accession, the authors of this Policy Brief believe it is essential to promote an operational strategy on security. Refusing to stop at the unpleasant state of affairs in the Western Balkans and the gloomy atmosphere in the EU member states, some practical reforms – well beyond declarations of intent – are expected from the French Presidency of the Council of the European Union. The authors of this Policy Brief seriously hope the French Presidency of the Council of the European Union will pay sufficient attention to the Western Balkans.

An unpleasant state of affairs

The Western Balkans must be considered as a priority area of interest and be the subject of a multisectoral response because the issues at stake are numerous and interdependent.

One of these challenges is the endemic presence of polycriminal groups drawing on Western European diasporas, coupled with continuing political tensions – corruption and weak administrative structures. They make security cooperation measures particularly difficult to implement. The lack of coordination with EU member states and among the Western Balkan countries further complicates any action on the ground.

From a French point of view, the Western Balkans are still a transit area for criminal trafficking, the legacy of the 1990-2000 conflicts also generates significant arms trafficking. As the main road for illegal immigration, the passage of large population movements through these countries fuels human trafficking, often coupled with pimping and drug trafficking networks. Eurosceptics insist on this negative image to justify their harsh criticism on the EU and to undermine Europe. According to the authors the EU should foster cooperation and communicate on the success stories.

The Western Balkans must be considered as a priority area of interest and be the subject of a multisectoral response because the issues at stake are numerous and interdependent.

Problems, although common to the region, should not be approached in a uniform manner: each country has its own specificities that must be taken into account. This situation unfortunately hinders the full effectiveness of operational cooperation. The treatment of these threats suffers firstly from the weakness of police and military cooperation. Information exchange is particularly lacking, mainly due to an absence of trust in local partners, preventing the establishment of a reliable and dynamic network in the area. Secondly, the corruption of these actors remains a concern, particularly because of the impunity of political decision-makers – chapters based on the rule of law have to be reinforced, specially throughout a European pillar on criminal law must be adopted.

These combined weaknesses represent threats to internal security throughout the continent. Therefore, it is essential to formalise an operational strategy adapted to the context and needs. Successes should be widely communicated.

Collection and exchange of information between EU member states and candidate countries

New working methods, open to a dense multilateral network, are needed with the aim to reinforce the pre-existing bilateral cooperation.

The nature of the threats outlined above in the region makes it necessary to rely on a structured network of officers deployed in these countries in order to create strong links between the EU member states and local security services. The effectiveness of this European network could be based on effective interoperability with international organisations, such as the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime or the Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe, and the EU agencies, Frontex and Europol, based in the region. New working methods, open to a dense multilateral network, are needed with the aim to reinforce the pre-existing bilateral cooperation.

At present, the countries in the region, with the exception of Kosovo, are connected to the Interpol network and are operational third states with Europol. However, the standardisation of access of corrupt services to European and international operational information systems still needs to be counteracted in order to intensify exchanges between investigative services in the Western Balkans and the EU member states.

With regard to bilateral relations, with a view to national and European influence, the sending of liaison officers to the region must continue in order to adapt the network to the challenges in the area. Of particular note are the permanent French criminal intelligence units which have been proving their worth in Serbia for several years and more recently in Bosnia and Herzegovina. This is a model that should be developed and perpetuated for better intelligence gathering but also because it offers an outreach which will be taken seriously in particular if we want to prove the existence of an efficient rule of law.

Of particular note are the permanent French criminal intelligence units, which have been proving their worth in Serbia for several years and more recently in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Based on the existing structures, the authors believe that it would be judicious to extend the prerogatives of these units to other criminal fields, such as human trafficking and the fight against drugs, and at the same time to extend the nature of the information collected to include bank data. This would increase the efficiency of investigations, establish the legitimacy of these structures and publicise their successes, at a time when the EU seems to be distinguished only by its “soft consensus” and the member states appear to be pursuing only their own interests. These bilateral structural developments should aim to extend the model of the Permanent Criminal Intelligence Units to other countries in the region to create a true intelligence community – with or without the EU – whose birth would be driven only by its indispensability.

Support and monitoring of migration flows

In the context of this reflection, the region must be considered as a transit zone rather than a place of origin of migration. Without evading this last point, it should simply be emphasized that migrants from the Western Balkans move mainly because of corruption and unemployment in their countries as well as because they belong to a discriminated group. What the authors are interested in here are the important flows in the area, which require networking to facilitate information exchange. It is therefore necessary to pool the efforts undertaken by each EU member state in monitoring flows and in the fight against human trafficking networks. Focusing exclusively on the illegal nature of a border crossing is of no use: it is necessary to support the areas that have to deal with these crossings on a daily basis, to study them in preparation and to identify businesses that do not respect European values.

Support for the initiatives carried out in the framework of the European Multidisciplinary Platform Against Criminal Threats (EMPACT), which aims to gather information through targeted checks, including documentary checks, would strengthen operational cooperation in the fight against human trafficking.

Beyond the pre-existing tools requiring a commitment from both EU member states, candidate and potential candidate countries, an inclusive approach should be envisaged in order to involve, for example, private transport actors. In this context, it is essential to be clear about the objectives pursued and to develop the exchange of information with the economic actors concerned.

In the context of this reflection, the region must be considered as a transit zone rather than a place of origin of migration.

The evaluation of migratory flows and the resulting traffic must be carried out through the development of new tools. Thus, the support given to local Structural Innovation Funds should be redirected into the creation of units dedicated to the collection of strategic information and the provision of equipment adapted to the processing of these data. Finally, this capacity building should include training on documentary, banking and tax fraud as well as the creation of dog units, to name a few examples. Benevolence must be shown, both to the authorities of the territories crossed and to the people who are the “objects” of this trafficking, because what poses a problem in the first place is the vigour with which transnational organised crime operates.

Combating transnational organised crime activities

Existing structures, which are not well known to the public, deserve to be promoted and developed. The EMPACT cycle appears to be the main operational tool in the fight against organised crime: its use in the Western Balkans must now be increased. This should be accompanied by an awareness of the FATF and MONEYVAL (Committee of Experts on the Evaluation of Anti-Money Laundering Measures and the Financing of Terrorism) standards, allowing for the development of “mirror investigations” and increasing the effectiveness of money laundering investigations. Following the same logic, as regards the fight against arms trafficking, the effort to deploy the EVOFINDER ballistic analysis system software must be continued. Finally, the adaptation of criminal information exchange tools to operational needs is essential. In this respect, extending the search possibilities in the EUCARIS (European car and driving licence information system) system would increase the chances of identifying the heads of criminal networks and thus the efficiency of investigations.

Structural cooperation must obviously be followed by operational cooperation with the aim of putting an end to arms trafficking and related criminal activities. Proving the effectiveness of this cooperation will reassure investors and decrease a – too often – shared feeling of legal insecurity. Procedures must therefore be put in place to enable all actors involved – local and Western – in the fight against organised crime to systematically rely on the Permanent Criminal Intelligence Units and to develop common tools and practices with the actors involved in the area.

Structural cooperation must obviously be followed by operational cooperation with the aim of putting an end to arms trafficking and related criminal activities.

All this should be complemented by: full cooperation in the framework of international commissions rogatory to avoid that many requests addressed to the authorities in the Western Balkans remain unanswered; the training of specialised local services; and the implementation of joint investigations that are widely publicised. All this must be supplemented by the development of the cyber investigation capabilities of the security forces of the countries in the region in order to detect criminal networks exploiting the capabilities of the Internet to develop their trafficking.

These institutional frameworks can only be effective if they are backed up by cooperation with the private actors involved – often unwillingly – in trafficking. This would take the form of a framework for cooperation with money transfer companies present in the Western Balkans in order to ensure that the fundamentals of compliance are respected, over and above the advantages in terms of intelligence that this could provide.

These institutional frameworks can only be effective if they are backed up by cooperation with the private actors involved – often unwillingly – in trafficking.

In conclusion, structural and operational cooperation between EU member states, candidate countries and potential candidate countries, but also between private and international actors, seems to be the best solution to fight against Europhobic discourse, to guarantee the rule of law and finally, to combat the various types of trafficking that take place in the Western Balkans. These joint efforts should strive towards preparing EU accession of the Western Balkan countries in a very efficient way.

Photo: People in front of the European flag / Photographer: Georges Boulougouris

© European Communities, 2004

Source: EC – Audiovisual Service

****************************

Antkowiak Christophe, The emergence of Eastern European mafias. What to do? Diploma memorandum of university of 3rd cycle, Directed by Mr Naudin, Paris, Université Panthéon-Assas, 2004, 85 p. https://creogn.centredoc.fr/doc_num.php?explnum_id=11

Coen Myrianne, Corruption as a weapon of destruction of the democratic state, Wall Street International, May 2020. https://wsimag.com/fr/economie-et-politique/62338-la-corruption-arme-de-destruction-de-letat-democratique

Corstens GJM, Criminal Law in the First Pillar? European Journal of Crime, Criminal Law and Criminal Justice, Vol. 11/1, 131–144, 2003.

https://www.google.com/url?sa=D&q=https://brill.com/previewpdf/journals/eccl/11/1/article-p131_7.xml&ust=1639733220000000&usg=AOvVaw10Qf0-zQGWe954ZRXVSbFT&hl=fr&source=gmail

Council of Europe, Two Western Balkan countries still struggle with migration flows but face different challenges, April 2019. https://www.coe.int/en/web/portal/-/two-western-balkan-countries-still-struggle-with-migration-flows-but-face-different-challenges

Eijssen Paul, EUCARIS, the European car and driving license information system, European Commission, April 2008, https://joinup.ec.europa.eu/collection/egovernment/document/eucaris-european-car-and-driving-licence-information-system-eucaris

EuropaNova, Newsletter Europe Info Hebdo, EuropaNova, 12 November 2020. https://uploads-ssl.webflow.com/594919aeb0d3db0e7a726347/5fae41a8b755ad766e542c3c_NL%20EuropaNova%2012.11.pdf

European Commission, Cooperation and Verification Mechanism for Bulgaria and Romania, European Commission. https://ec.europa.eu/info/policies/justice-and-fundamental-rights/upholding-rule-law/rule-law/assistance-bulgaria-and-romania-under-cvm/cooperation-and-verification-mechanism-bulgaria-and-romania_en

European Commission, Enlargement 2004: the challenge of an EU of 25, European Commission, January 2007. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/FR/TXT/HTML/?uri=LEGISSUM:e50017&from=EN

European Commission, 2020-2025 EU action

plan on firearms trafficking, European Commission, July 2020. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=COM%3A2020%3A608%3AFIN

European Council, Sofia Declaration, EU-Western Balkans Summit, 17 May 2018. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/34776/sofia-declaration_en.pdf

France 24, Interpol again rejects Kosovo’s membership bid, 20 November 2018. https://www.france24.com/en/20181120-interpol-again-rejects-kosovos-membership-bid

Frison-Roche Marie-Anne, Dufour Olivia, Compliance law can help prevent global crises, Actu Juridique, April 2020. https://www.actu-juridique.fr/droit-de-la-regulation/le-droit-de-la-compliance-peut-contribuer-a-prevenir-les-crises-mondiales/

Frontex, Operations in the Western Balkans, Frontex. https://frontex.europa.eu/we-support/main-operations/operations-in-the-western-balkans/

Gossiaux Jean-François, Balkan societies and the war of the worlds, Diasporas, 23-24, 2014. http://journals.openedition.org/diasporas/321

IRIS, Report on the seminar Arms Trafficking in Post-Conflict Situations: Case Studies and Issues, IRIS and GRIP, January 2017. https://www.iris-france.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/Synth%C3%A8se-Compte-rendu-S%C3%A9minaire-du-24-janvier.pdf

Kemeny Gabor, The present and the future of cross border police and customs information exchange between the EU and the Western Balkan region. Public Security and Public Order, 20. 2018, pp. 117-133. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/325976451_The_present_and_the_future_of_cross_border_police_and_customs_information_exchange_between_the_EU_and_the_Western_Balkan_region

Krasniqi Kole, Organized Crime In The Balkans, European Scientific Journal, ESJ, 12(19), 204, 2016. https://eujournal.org/index.php/esj/article/view/7727

Krulić Joseph, The Balkan refugee route. August 2015 – March 2016, Hommes & Migrations, 2020/1 (No. 1328), pp. 27-33. https://www.cairn.info/revue-hommes-et-migrations-2020-1-page-27.htm

Lagneau Laurent, For Paris, arms trafficking in the Balkans is still a major threat to European security, Zone militaire, December 2018.

Lagneau Laurent, Plans for an EU rapid reaction force resurface, Zone militaire, May 2021,

http://www.opex360.com/2021/05/07/un-projet-visant-a-doter-lunion-europeenne-dune-force-de-reaction-rapide-refait-surface/

Le Pen Marine, White paper on security, February 2020, https://rassemblementnational.fr/telecharger/publications/Livre%20Blanc%20-%20Secu_FUSION_OKBAT_STC.pdf

Lepensant Gilles, 2004-2014: taking stock of a decade of enlargement, Fondation Robert Schuman, n°311, April 2014. https://www.robert-schuman.eu/fr/questions-d-europe/0311-2004-2014-bilan-d-une-decennie-d-elargissements

Mastrorocco Raffaele, OSCE and Civik Society in the Western Balkans: The Road to Reconciliation, in Mihr A (ed), Transformation and Developpement, Springer, Cham, 2020. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007%2F978-3-030-42775-7_6

Mikóvári, Orbán Viktor: “Immigration also threatens security in Hungary”, Hongrie Actuelle, November 2015. https://hongrieactuelle.wordpress.com/2015/11/18/orban-immigration-menace-aussi-securite-hongrie/

MONEYVAL, Committee of Experts on the Evaluation of Anti-Money Laundering Measures, Financial Action Task Force. https://www.fatf-gafi.org/pages/moneyval.html

Nivet Bastien, European Union: a depoliticisation conducive to populism, International and Strategic Review, 2011/4 (No. 84), pp. 16-27. https://www.cairn.info/revue-internationale-et-strategique-2011-4-page-16.htm

Presidency of the French Republic, French strategy for the Western Balkans, Press service and watch of the Presidency of the Republic, April 2019. https://me.ambafrance.org/IMG/pdf/04_26_note_technique_-_strategie_francaise_pour_les_balkans_occidentaux.pdf

Stratulat Corina, Lazarević Milena, Discussion paper, The Conference on the Future of Europe: Is the EU still serious about the Balkans? European Policy Centre, p. 6, October 2020, https://conference-observatory.eu/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/The-Conference-on-the-Future-of-Europe-Is-the-EU-still-serious-about-….pdf

Statista, The Relentless Rise Of Populism In Europe, Statista, May 2019. https://www.statista.com/chart/17860/results-of-far-right-parties-in-the-most-recent-legislave-elections/

About the article

ISSN 2305-2635

The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Austrian Society of European Politics or the organisation for which the authors are working.

Keywords

European Union, Western Balkans, integration, enlargement, Euroscepticism, security, cooperation, migration

Citation

Bernard, E., Leloup, J. (2022). Considering EU enlargement through the prism of security cooperation. Vienna. ÖGfE Policy Brief, 01’2022