Policy Recommendations

- Introduce fixed amounts of party funding to increase financial predictability, and raise parties’ lump sum to improve fairness.

- Move to vote-based funding to reward electoral results and individual-member-based funding to increase citizen participation.

- Use a matching fund to strengthen private funding.

Abstract

Political parties are core stakeholders of modern representative democracies and fill a number of important functions in the political system. At the European level, however, European parties fail to properly meet most of these functions and, therefore, to live up to their role prescribed in EU treaties. In particular, European parties’ current funding scheme, relying almost exclusively on public funding and making Members of the European Parliament (MEPs) the paramount barometer for performance, fails to create a true level playing field between parties, does not fairly reward electoral performance, and is a poor way to incentivise political parties to reach out to citizens.

European Democracy Consulting calls for reform of European parties’ funding system in order to enhance their relevance, increase their visibility, and encourage citizen participation in the EU’s political life. In particular, this Policy Brief proposes to replace split-envelope budgeting with fixed amounts to increase financial predictability, to increase parties’ lump sum to improve funding fairness, to replace MEP-based with vote-based funding to reward electoral results, to create individual-member-based funding to increase citizen participation, and to use a matching fund to strengthen private funding.

While a number of other reforms are needed to strengthen European parties — including a reform of their status, of registration criteria, and of their implication in national political life — the reform of the EU’s party funding scheme is paramount. By increasing overall public funding and, more importantly, by awarding it more appropriately, the EU could bring European parties closer to citizens while ensuring that all parties, large and small, are given a fair chance in the political arena.

****************************

A smarter funding system for European parties

Introduction

Political parties are core stakeholders of modern representative democracies: not only do they exist in all democratic systems, but their absence or curtailment is directly seen as hampering the proper representation of citizens.

As often, the European Union harbours a complex system. Democracy and pluralism are founding values of the Union[1] and EU treaties state that political parties at European level “contribute to forming European political awareness and to expressing the will of citizens of the Union.”[2] Nevertheless, these European parties are all but foreign to citizens and, even during European elections — by all measures the most “European” moment of the Union’s political life — citizens continue to rally behind and vote for national parties.[3]

In modern politics, funding is arguably among the most crucial elements of a political party’s functioning[4] and, together with the acquisition of political power, stands as the most powerful incentive the legislator can leverage in order to bring about a desired behaviour or outcome — from increasing gender balance, to ensuring transparency, controlling income and expenditure, etc. In particular, the behaviour of political parties in party systems in formation, such as the EU, can be directly influenced by conditions on the receipt and use of public funding, allowing them to efficiently support the creation of a mature European political party system.[5]

In order to enhance European parties’ role, increase their visibility, and encourage citizen participation in the EU’s political life, European Democracy Consulting argues that a vast array of incentives can be found in the design of European parties’ funding system. Ahead of the European Parliament’s implementation report on Regulation 1141/2014 on European parties,[6] this policy paper briefly recalls the role of political parties and European parties, highlights the current rules for the funding of European parties, and details actionable reform proposals.

The role of European political parties

The role of modern political parties can be summed up in seven major functions, and each highlights the limited impact of European parties compared to their national counterparts.[7]

Political parties structure the vote through party labels, allowing citizens to match their interests and values with a party label. European parties, however, are forbidden from partaking in national and sub-national elections. Even for European elections, citizens mostly cast their ballot in favour of national parties.

Secondly, political parties serve to mobilise and socialise the population by connecting citizens to the political system and increasing their attachment to that system. However, with a low level of recognisability and a limited focus on individual membership, European parties do not trigger nearly the same level of activist mobilisation that national parties are able to muster.

Thirdly, political parties also contribute to candidate selection, whether through party leaders or primaries. The role of European parties in candidate selection is close to non-existent, as national parties exercise a monopoly on candidate selection and list arrangement for European elections. Likewise, Commissioners are nominated by national governments and the President of the Commission becomes the subject of horse-trading in the European Council. While the SpitzenkandidatInnen system could have increased their role, it was only supported by a fraction of European parties, and eventually discarded by the Council.

A fourth function consists in the aggregation of interests of sections of the population, with some parties representing a specific class, from large societal cleavages (socialist or christian-democratic parties) to specific interest groups (pirate, animalist or hunters’ parties). Some European parties have proved ideologically coherent, but many remain large catch-all coalitions.

Fifth, political parties contribute to the development of public policy by drafting policy positions and influencing the policy-making process. European parties only contribute marginally to policy formulation, due to the limited competences of the European Parliament and because of their lack of ideological homogeneity. Instead, they often settle on minimum common denominator positions, leading to short, undetailed, and rarely engaging manifestoes and limited support for the party line.

Political parties contribute to structuring the relations between the legislative and the executive branches. European parties provide this link through their congresses and pre-European Council summits. However, given the difficulty to constrain Heads of States or Governments, these events remain general exchanges of views and do not lead to unified positions.

Compared to national parties, European parties currently enjoy a very limited role.

Finally, deriving from the previous functions, parties contribute to the legitimacy of the overall political system by ensuring representativeness, providing stability and cementing popular support. Being weak on all other functions, European parties fail to create a tangible link with citizens. They seldom try to speak to them, and even more rarely succeed.

Compared to national parties, European parties currently enjoy a very limited role. However, given the importance of parties in modern democracies, this can and should be made to change. Funding schemes may be used for this purpose.

Funding of European political parties

Current rules for European party funding[8]

Public funding. Appropriations for political parties feature in the budget of the European Parliament and are divided as follows to qualifying parties:[9] 10 percent are split as a lump sum and 90 percent are distributed based on parties’ number of Members of the European Parliament (MEPs). However, public funding cannot exceed 90 percent of a party’s annual reimbursable expenditure — meaning at least 10 percent must be raised from private funds.

Private funding. Donations from legal and natural persons are limited to €18,000 per year and per donor.[10] Every year, parties submit, along with their financial statements, a list of all donors, including the value and nature of each donation.[11] Parties are forbidden from accepting donations from anonymous donors, European political groups, public authorities, or natural and legal persons from third countries.

Spending limitations. European parties are allowed to finance campaigns for European elections in which they or their members participate; provisions on funding and spending limits remain governed by national law. However, European parties are explicitly forbidden from directly or indirectly financing other parties, including national parties and candidates, or referendum campaigns.

Consequences of the European public funding scheme

The introduction of public funding in 2004 led to an immediate increase in European parties from five to eight, with the creation of the European Left (far left), of the European Democratic Party (centrist, breaking off from the EPP), and of the Alliance for a Europe of Nations (far right). The number of parties continued to grow, peaking at 16 in 2017 before settling on its current 10. Far-right parties have proved the least stable, with such parties forming and crumbing every few years.

| European Political Parties[12] | European Parliamentary Groups[13] |

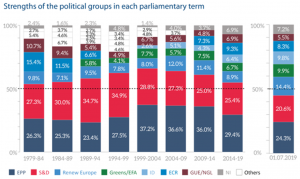

By contrast, European parliamentary groups (which gather MEPs by ideology in the European Parliament and have existed since the late 1950s) have remained largely stable over time (see chart below).[14]

Source: European Parliamentary Research Service Blog

The increase in the number of parties has meant the broadening of the European party system’s spectrum, mostly through the creation of parties on the far left and far right. While we may disagree with their message, a healthy democracy requires the possibility for all political movements to constitute as parties, and the broadening of the EU’s political spectrum was an essential feature of its democratisation.

Current figures for party funding[15]

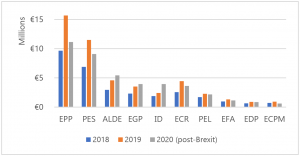

For the year 2020, €42 million of the European Parliament’s budget were allocated to the financing of European parties — a slight decrease from the previous year’s €50 million, following a drop in the EU’s post-Brexit population.[16] This amount represents a cost of €0.09 per year per European citizen.

Over half of this allocation went to the EPP and PES (€11 million and €9 million, or 27 and 22 percent, respectively).[17] ALDE, the EGP, ID and the ECR each received between €5.4 million and €3.6 million (13 down to 9 percent). Forming a third block, the PEL, EFA, EDP and ECPM received between €2.1 million and €0.6 million (5 down to 1.4 percent).

More generally, European political parties are far outpaced by their national counterparts in terms of per-capita subsidy and, often, also in absolute amounts.

By contrast, in 2020, federal subsidies for Austrian political parties amounted to €30.7 million, including €11.6 million received by the leading political party, the ÖVP.[18] With a population under 9 million inhabitants, federal subsidies amounted to €3.54 per year per Austrian citizen. More generally, European political parties are far outpaced by their national counterparts in terms of per-capita subsidy and, often, also in absolute amounts.

Source: European Parliament[19] / Design: European Democracy Consulting

Views differ on the role of European parties and the scope their activities should have. Nevertheless, even with a limited role, European parties’ public funding can only be considered as far insufficient for their concrete involvement in the political landscape. Of course, the objective should not be to merely increase the amount of public party funding, but instead to reach a fairer distribution between the European and national levels, reflecting new and more balanced roles of national and European parties. Since national and European public funding systems remain separate, this balancing act ought to start with increased appropriations for European parties.

Yet, while increasing European parties’ budgets is undoubtedly a prerequisite to strengthen their organisation and expand their activities, the manner in which these funds are allocated is crucial to the democratisation, openness and fairness of the EU’s party system.

The objective should not be to merely increase the amount of public party funding, but instead to reach a fairer distribution between the European and national levels, reflecting new and more balanced roles of national and European parties.

Reform proposals

Proposal 1: Replace split-envelope budgeting with fixed amounts to increase financial predictability

Each year, the European Parliament’s Secretary General makes an estimate of the total funding envelope to be allocated to European parties. This amount must then be approved by the Bureau of the European Parliament,[20] the European Parliament’s Committee on Budgets, and the Plenary. Once the EU’s overall budget is approved, qualifying parties equally split 10 percent of this amount as a lump sum and the remaining 90 percent in proportion to their number of MEPs.

As a result, a party’s funding is tied to yearly negotiations and is directly affected by the number of parties qualifying for funding. In a volatile party system as the EU’s, where the number of parties highly fluctuates, this is detrimental to parties’ long-term financial planning.[21]

Even if the agreed funding envelope aims at accounting for the number of parties qualifying for funding, fluctuations in the number of parties and in small parties’ ability to qualify[22] mean that funding may jump up or down irrespective of parties’ direct performance.

For more predictable funding, and still keeping the EU’s current division between lump sum and number of MEPs, one could consider a fixed amount for the lump sum and a fixed amount per MEP. For instance, Austria has a fixed lump sum of €218,000 per party with at least 5 national MPs. Using 2020 figures and the 580 MEPs affiliated to a European party,[23] each MEP should entitle its party with around €65,000 per year. A planned increase based on a consumer price index, as is the case in Austria,[24] removes the need for yearly review of the agreed amounts.

Proposal 2: Increase parties’ lump sum to improve fairness

An essential aspect of a well-designed public funding system is to create a level playing field between parties, in particular for smaller and newer ones, upon which often rests the representation of minority groups and the renewal of the political class.

Endowed with limited resources, these parties are inherently more vulnerable to rising expenses, legal fees, allocation changes, and other financial risks. They are also more easily affected by electoral results, as a change of just a few MEPs may mean life or death when MEP-based funding accounts for 90 percent of all public funding.

By contrast, since 2004, the EPP and PES combined have consistently received over half of the EU’s party funding, despite the presence of up to 16 receiving European parties, and a 2018 reform has actually decreased the lump sum from 15 to 10 percent of the funding envelope — further advantaging the largest parties.

Should the current split-envelope mechanism remain in place, one could reverse the 2018 reform and instead increase the lump sum, for instance, to 20 or 25 percent.[25] Should the lump sum become fixed, its amount should be evaluated based on real costs for common operations, including staff and administrative costs, communications expenses, and real estate in Brussels.

Proposal 3: Replace MEP-based with vote-based funding to reward electoral results

While European elections are mostly proportional, half of the Member States enact electoral thresholds[26] of up to 5 percent;[27] consequently, many small parties fail to enter the European Parliament despite electoral support from citizens.

From a funding point of view, votes for these parties are lost: citizens voting for large parties are indirectly provided the opportunity to financially support their favourite European party, but citizens voting for small parties are denied this opportunity. In order to properly reward the electoral performance of all parties, the current MEP-based funding could therefore be replaced with one based on each party’s votes received in the European election.

Beyond being fairer, this mechanism has two useful consequences. First of all, vote-based funding remains fixed between elections, which places more emphasis on the elections, encouraging parties to perform well.

Secondly, there is less incentive to create a new party and benefit from funding linked to MEPs switching sides: any new party created between elections could receive public funding (for instance, the lump sum), but not funding tied to an election it did not directly participate in. This increases financial predictability and brings more stability to the party system.

Moving away from split-envelope funding, parties could receive a given sum per vote, either with a fixed rate or using regressive brackets. In Austria, each vote entitles a party to roughly €4.6;[28] in Germany, the first 4 million votes provide €1, and further votes €0.83. Using a fixed sum also encourages parties not only to seek a high share of the vote, but also a high number of votes, and gives them a direct incentive in raising voter turnout — a critical issue when it comes to European elections.

Proposal 4: Create individual-member-based funding to increase citizen participation

The distance between citizens and European parties severely limits the creation of a true European party system, and, consequently, of a European political sphere: citizens ignore European parties and, when seeking to be politically active, join national parties instead.

Conversely, European parties have no incentive to reach out: citizens vote for national parties and national candidates, and campaigns are carried out at the national level. Furthermore, a small individual membership (with dozens of members, instead of hundreds of thousands) makes organisational processes and membership-based votes easier.

As a result, individual membership in European parties is, by and large, inexistent and mostly limited to MEPs and certain office-holders. As of May 2020, European parties’ average number of individual members stood at 192, and, without ALDE and the PEL, fell just over 21.[29]

While changing the selection of candidates or the organisation of campaigns requires reforming the European electoral law, we can use public funding to incentivise the direct membership of European parties and increase citizens’ political participation. In the Netherlands, this takes the form of a funding scheme accounting for parties’ number of members: the more members a party has, the more funding it receives.

A highly regressive system should be put in place: the first tens of thousands of members would be highly valued, while the following ones would have a much lower value. Ceilings would avoid unwanted skyrocketing costs, and safeguards would include a minimum number of members, a minimum membership fee to be paid by members, and giving members voting rights for party leadership.[30]

Finally, a multiplying coefficient should be designed to reward a party’s presence in a large number of Member States, instead of only building a strong presence in one or a few states.[31] The criteria of “presence” could be roughly proportional to each Member State’s size, akin to the requirements of a European Citizens’ Initiative.[32]

Proposal 5: Use a matching fund to strengthen private funding

Beyond party membership, a key element in bringing political parties and citizens closer is for parties to actively engage citizens through public campaigns and activities. Parties will engage in these if they hope to derive votes or financial support.

Therefore, while public financing is important in ensuring that parties are sufficiently funded and not captured by lobbies or waste time in endless fundraising, the ability to raise private funding can be a powerful tool for parties to be closer to citizens. Here, too, public funding can be used as an incentive and to achieve balance between public and private funding streams.

Current rules limit EU public funding to 90 percent of European parties’ reimbursable income. However, with funding tied exclusively to the lump sum and MEPs, there is no public incentive to raise more than 10 percent in private funds. In practice, European parties are indeed extremely dependent on public funding, between 75 and 90 percent of their income.[33]

Conversely, Germany matches parties’ private funding with €0.45 for every euro received, regardless of the source — donations, membership fees, contributions from office holders, etc. —, thereby encouraging parties to raise private capital.[34] In exchange, total public funding cannot exceed private funding, meaning that political parties must generate 50 percent of their income from private sources. This is probably ambitious for European parties, but the current 90/10 ratio could progressively decrease in order to provide for a progressive increase in private donations.

In part through these incentives, German parties have the lowest level of dependence on public funding (around 40 percent), the lowest membership drain, and the highest trust in political parties.[35]

Conclusion

Overall, the EU’s current funding scheme, relying almost exclusively on public funding and making MEPs the paramount barometer for performance, fails to create a true level playing field between parties, does not fairly reward electoral performance, and is a poor way to incentivise political parties to reach out to citizens.

A number of other reforms are needed to improve this financing situation, including extracting party funding from the budget of the European Parliament and placing it directly under the EU budget, allowing European parties to finance affiliated national parties and candidates, creating special time-limited financing rules for new parties to facilitate the emergence of newcomers, introducing specific campaign reimbursements for European elections, or using conditionality to support specific policy goals and values, such as gender balance.[36] And more reforms still will be necessary to strengthen European parties — including a reform of their status, of registration criteria, and of their implication in national political life.

Nevertheless, by increasing public funding and, even more importantly, by awarding it more appropriately through the proposed reforms, the EU could amend Regulation 1141/2014 and start building a smarter funding system that supports the objectives of bringing European parties closer to citizens while ensuring that all parties, large and small, are given a fair chance in the political arena.

[1] Treaty on European Union, Article 2.

[2] Treaty on European Union, Article 10.4 (the so-called “Party Article”).

[3] Hertner, Isabelle, “Europarties and their grassroots members: an opportunity to reach out and mobilize.” in Reconnecting European Political Parties with European Union Citizens, edited by Tobias Wolff, International IDEA, Discussion Paper 6/2018, p. 31.

[4] Bardi, Luciano et al., How to create a Transnational Party System, European Parliament, 2010, p. 75.

[5] Bardi, Luciano et al., ibid, p. 74.

[6] Regulation (EU, Euratom) No 1141/2014 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 October 2014 on the statute and funding of European political parties and European political foundations, http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2014/1141/oj

[7] Van Hecke, Steven and Wolfs, Wouter, “What are European political parties and what do they do?” in Reconnecting European Political Parties with European Union Citizens, ibid, p. 18.

[8] Regulation (EU, Euratom) No 1141/2014, ibid. The direct and indirect public funding of European parties began with Regulation 2004/2003 and was amended through subsequent regulations.

[9] Registered European parties are required to have at least one MEP to apply for funding.

[10] This ceiling does not apply to members of European, national or local parliaments. Contributions from party members cannot exceed 40 percent of a party’s budget.

[11] Funding-related provisions for transparency require the public disclosure of donations above €3,000, as well as of donations between €1,500 and €3,000 for which donors have consented to the disclosure.

[12] Data: European Parliament, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/contracts-and-grants/files/political-parties-and-foundations/european-political-parties/en-funding-amounts-parties-2020.pdf / Design: European Democracy Consulting.

[13] These relationships are not always exact. According to the latest figures provided by the European Parliament and European parties, there are currently nine members of European parties seating in a different parliamentary group than the one to which their party is affiliated (mostly EFA members not seating with the Greens/EFA). There are another 62 MEPs seating with a group but not members of a European party (mostly Renew Europe and ID Group). More information at: https://eudemocracy.eu/meps-party-and-group-data

[14] https://epthinktank.eu/2014/11/26/european-parliament-facts-and-figures/5-strengths-of-political-groups-4/

[15] https://eur-lex.europa.eu/budget/www/index-en.htm

[16] https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/tgm/table.do?tab=table&init=1&language=en&pcode=tps00001&plugin=1

[17] https://www.europarl.europa.eu/contracts-and-grants/files/political-parties-and-foundations/european-political-parties/en-funding-amounts-parties-2020.pdf

[18] https://www.bundeskanzleramt.gv.at/dam/jcr:43c955d7-75fb-4bf8-8965-81739bdcc3d3/Parteienfoerderung_2010-2020.pdf

[19] https://www.europarl.europa.eu/contracts-and-grants/files/political-parties-and-foundations/european-political-parties/en-funding-amounts-parties-2020.pdf

[20] The Bureau of the European Parliament is composed of the President of the European Parliament along with all 14 Vice-Presidents (roughly proportional to Parliamentary groups’ share of Parliament, but with the notable exclusion of Eurosceptic parties) and the five Quaestors (who oversee administrative and financial matters directly affecting MEPs), in a consultative capacity.

[21] This includes a doubling of the number of parties over between 2005 and 2015, and the disappearance of 6 out of 16 parties between 2017 and 2018.

[22] In order to register as a European party, a group of national parties must meet a number of criteria listed in Regulation 1141/2014. In particular, its member parties must be represented, in at least seven Member States, by MEPs, MPs, or members of regional parliaments. Alternatively, its member parties must have received, in at least seven Member States, three per cent of the votes at the most recent European elections.

[23] http://www.appf.europa.eu/appf/en/parties-and-foundations/registered-parties.htm

[24] Bundesgesetz über Förderungen des Bundes für politische Parteien (Parteien-Förderungsgesetz 2012 — PartFörG), BGBl. I Nr. 57/2012, paragraph 5.

[25] Even with a 25% lump sum, the spread between the EPP’s share of MEPs and share of total funding is lower than 5 points and no party gains more than 3 points.

[26] https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/ATAG/2018/623556/EPRS_ATA(2018)623556_EN.pdf

[27] A 2019 reform further compels all constituencies larger than 35 seats to enact thresholds of at least 2 percent.

[28] Austria operates indirectly: parties actually receive a proportion of the overall funding equal to their share of the vote, but said overall funding is calculated as €4.6 per person entitled to vote.

[29] European Parliament, Number of individual members, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/contracts-and-grants/files/political-parties-and-foundations/audit-reports-and-donations/en-the-total-number-of-individual-members-2020.pdf

[30] In the Netherlands, parties are required to have at least 1,000 members paying a membership fee of at least €12.

[31] As a result of this multiplying coefficient, the more Member States a European party is effectively present in, the more funding it receives. For instance, funding could double if a European party has sufficient individual members in all Member States. This coefficient could decrease in importance as the practice of individual members becomes more widespread.

[32] European Commission, Minimum numbers of signatories for initiatives registered since 01/02/2020, https://europa.eu/citizens-initiative/thresholds_en

[33] https://www.europarl.europa.eu/contracts-and-grants/en/political-parties-and-foundations/audit-reports-and-donations

[34] A ceiling of €3,300 per donor caps this system.

[35] Casal Bértoa, Fernando and Teruel, Juan Rodríguez, Political Party Funding Regulation in Europe, East and West: A Comparative Analysis, OSCE-ODHIR, 2017.

ISSN 2305-2635

The views expressed in this publication are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Austrian Society of European Politics or the organisation for which the author is working.

Keywords

European parties, political parties, party funding, public funding, reform

Citation

Drounau, L. (2021). A smarter funding system for European parties. Vienna. ÖGfE Policy Brief, 01’2021