Policy Recommendations

The European Union should

- establish a permanent EU investment fund amounting to at least 1% of EU economic output per year to finance green public investment.

- finance the needed investments through the emission of EU bonds as it was done for financing Recovery and Resilience Facility

- undertake genuine European investment projects with EU added value such as a European high-speed train system, an integrated electricity grid for the transmission of 100% renewable energy, as well as the support of complementary battery and green hydrogen projects.

Abstract

Policy-makers need to increase public investment in the European Union (EU) for a green shift in European economies to achieve the ambitious climate and energy targets and to make our energy systems less dependent of imported fossil fuels. Reaching the 2030 climate targets requires additional public investment for green purposes equivalent to at least 1% of EU economic output per year. However, the reform proposals of the EU fiscal rules by the European Commission will in all likelihood fail to sufficiently expand the scope for green public investment. What the European community needs is a permanent EU Climate and Energy Investment Fund amounting to at least 1% of EU economic output to finance public investment. Such a central investment capacity would substantially relieve national budgets of EU member states, allow governments to take an important step in the green transition while making it more realistic to comply with EU fiscal rules. Furthermore, it would not only strengthen the community of EU member states economically and politically from within but also promote its geostrategic capacity to act.

A Permanent EU Investment Fund for Tackling the Climate and Energy Crisis

The need for additional green investment in the EU

The member states of the European Union (EU) need to increase public investment to transform the energy and transport system and achieve climate targets. The necessity to accelerate the expansion of public investment has also been highlighted due to the geopolitical circumstances surrounding the war in Ukraine, the price increases caused by fossil fuels, and aggressive green industrial policies promoted by public spending in the US and other economic blocs. Current public investment in the EU is not sufficient to address climate targets and existing fiscal rules (e.g. Darvas and Wolff 2021; Pekanov and Schratzenstaller 2020). The prospective reform of EU fiscal rules as announced by the European Commission (2022) will in all likelihood not sufficiently expand the scope for public investment at the required scale. The establishment of a permanent EU investment fund for climate and energy would facilitate the necessary additional investments.

The prospective reform of EU fiscal rules as announced by the European Commission (2022) will in all likelihood not sufficiently expand the scope for public investment at the required scale.

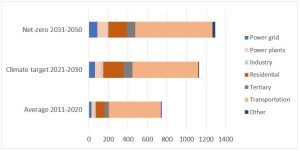

How large should such an EU investment fund be? The EU climate target until 2030 and the goal of becoming climate neutral by 2050 will require significant additional investment. An impact assessment report of the European Commission communicates that meeting the 2030 climate target would require an expansion of existing green investments of about 2% of annual EU gross domestic product (GDP) for the energy and transport sectors (EC 2020; Cornago and Springford 2021). This would require an additional €385 billion per year on average (at 2021 prices), an increase from the current €740 billion of investment per year to €1,125 billion per year (see figure 1). Wildauer et al. (2020) criticise the additional investment requirements communicated by the European Commission as an underestimate and argue in favour of an additional investment amount of 6% of EU economic output per year. To meet these investment needs, the public sector will need to launch much of this investment as it can mobilise investment of the private sector that is yet unprofitable (e.g., Darvas and Wolff 2022; Deleidi et al. 2020). Due to a wide range of estimates and market-related uncertainties, we suggest that about half of the additional annual investment should come from the public side. With the lower limit of 2% of EU GDP in annual additional total investment, this means that public investment for climate and energy of at least 1% of EU economic output should be undertaken annually.

Due to a wide range of estimates and market-related uncertainties, we suggest that about half of the additional annual investment should come from the public side.

Figure 1: Average yearly requirements for additional green investment in the EU

Source: European Commission 2020; own calculations.

Fiscal consolidation pressure limits scope for investment

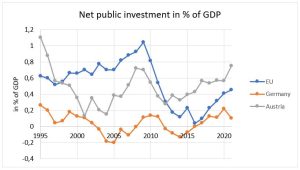

Net public investment fell markedly in the EU after the financial crisis and has not fully recovered. Austria performed better than many other EU countries in terms of investment but has at least equally significant additional investment needs (Delgado-Tellez et al. 2022).

Source: European Commission.

The EU goal of becoming climate-neutral by 2050 requires substantial additional investment. The share of public money for climate investment needs to be significant and, as argued, amount to at least 1% of EU economic output per year for the conversion of the energy and transport sectors. While some green investment is unprofitable for the private sector, the private side can be mobilised through public investment. In terms of intergenerational equity, it is necessary and appropriate to finance a significant portion of climate investments through public debt; because future generations benefit substantially from these investments and should thus share in their financing.

While some green investment is unprofitable for the private sector, the private side can be mobilised through public investment.

While national and European institutions largely recognise the investment requirements, solutions remain inadequate when it comes to the question how to finance them. For example, the European Commission recently published its ideas for reforming the EU fiscal rules, which set deficit and debt limits for national fiscal policy-makers of Austria and other EU member states.

While the focus, according to the European Commission’s proposal, is on a medium-term reduction of public debt ratios, there would be no far-reaching exemptions for climate investments. Austria, like other EU member states, will hardly be able to undertake the additional public investment for transforming the energy and transport systems to the extent required, while at the same time reducing the public debt ratio as called for. Fiscal consolidation pressures are mounting in the wake of the COVID-19 crisis and the energy crisis, and public investment is bound to suffer as it can be cut or postponed more easily than other government expenditures.

While the focus, according to the European Commission’s proposal, is on a medium-term reduction of public debt ratios, there would be no far-reaching exemptions for climate investments.

A new EU investment fund for climate and energy

We argue that the establishment of a new permanent EU Climate and Energy Investment Fund of at least 1% of EU economic output per year to finance public investments would be an important step towards a green turnaround and would relieve the burden on national budgets of EU member states (Heimberger and Lichtenberger 2023).

For the establishment of the new EU investment fund for climate and energy, the positive experiences with the Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF) launched during the Corona crisis could be used. The RRF is meant to promote the recovery from the COVID-19 crisis; it corresponds to an initial large-scale EU-wide investment initiative that pursues, among other things, decarbonisation goals. But it is not nearly sufficient to address investment needs due to climate change and the energy crisis. Achieving the EU’s 2030 climate target would require an expansion of public investment on the order of ten times the green investment share of the RRF.

For the establishment of the new EU investment fund for climate and energy, the positive experiences with the Recovery and Resilience Facility launched during the Corona crisis could be used.

To finance the new EU Climate and Energy Investment Fund, the European Commission would issue its own bonds on behalf of the EU, following the model of the RRF, to raise the funds on the financial markets. Member states would not be individually liable for the EU bonds issued; the liability would remain with the EU. The use of the investment funds by the EU member states is tied to green conditionality; thus, the investments must promote the achievement of climate and energy goals. While debt raised by individual member states increases national debt ratios, creating conflicts with EU fiscal rules, grants financed through EU bonds would not pass through to national debt ratios.

The EU bonds could be serviced by a revenue stream of new EU own resources. As proposals for such EU own resources, the European Commission cites revenues based on a revised EU emissions trading system and a newly introduced carbon border adjustment mechanism, as well as the reallocation of taxation rights for profits of large multinational companies. But there are other possibilities; for example, in relation to the taxation of wealth and top incomes at the EU level. The financing of a permanent EU investment fund could be designed from a combination of different instruments. Another option is not to (fully) service EU bonds with EU own resources and to allow the build-up of an EU debt stock.

Investments financed by the EU Climate and Energy Investment Fund could focus more on genuinely European projects in the field of transforming energy and transport systems to create EU added value. Examples include investments in a European high-speed train system that could reduce CO2 emissions in the transport sector in the long term. In the area of energy and decarbonisation, the realisation of an integrated electricity grid for the transmission of 100% renewable energy as well as the support of complementary battery and green hydrogen projects would be an option (Creel et al. 2020).

Investments financed by the EU Climate and Energy Investment Fund could focus more on genuinely European projects in the field of transforming energy and transport systems to create EU added value.

Conclusions

The European Commission’s current proposals to reform EU fiscal rules fail to provide the required scope for public investment. In view of the foreseeable increase in fiscal consolidation pressure, national budgets should be relieved by the establishment of a permanent EU investment fund for climate and energy, providing annual investments of at least 1% of EU economic output. This would allow economic policy to address the large investment needs in transforming energy and transport systems. Such an EU investment fund would not only promote the necessary investments to protect the climate and the environment, but also mobilise private investment, support key industrial sectors and contribute to a stable development of the European economic area. This would also help European companies to compete with their peers in the United States and elsewhere, where sovereign governments have supported their green industries with sizeable additional public spending.

A permanent EU investment fund could not only strengthen the community of EU member states economically and politically from within, but also promote its future geostrategic capacity to act in uncertain times.

Energy and climate crises represent common, cross-border European challenges that can best be addressed through common European solutions. Coordinating investment efforts and securing their financing to achieve climate and energy goals can be achieved more efficiently at the EU level than at the nation-state level. A joint credit-financed effort with cost-sharing between generations also reduces pressure for national tax increases in the present. A permanent EU investment fund could not only strengthen the community of EU member states economically and politically from within, but also promote its future geostrategic capacity to act in uncertain times.

****************************

Photo: AndreasAux / Pixabay

Cornago, E., Springford, J. (2021). Why the EU’s recovery fund should be permanent. Policy Brief, July 14, Centre for European Reform (CER), https://www.cer.eu/publications/archive/policy-brief/2021/why-eus-recovery-fund [last downloaded on September 21st 2022].

Creel, J. (2020). How to spend it: a proposal for a European Covid-19 recovery programme. The Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies (wiiw) Policy Report, No. 38.

Darvas, Z., Wolff, G. (2021). A green fiscal pact: climate investment in times of budget consolidation. Bruegel Policy Contribution, 18/2021.

Darvas, Z., Wolff, G. (2022). How to reconcile increased green public investment needs with fiscal consolidation. VoxEU.org, 7.3.2022, https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/how-reconcile-increased-green-public-investment-needs-fiscal-consolidation [last downloaded on November 10th 2022].

Delgado-Tellez, M., Ferdinandusse, M., Nerlich, C. (2022). Fiscal policies to mitigate climate change in the euro area. ECB Economic Bulletin, 6, https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/economic-bulletin/articles/2022/html/ecb.ebart202206_01~8324008da7.en.html [last downloaded on January 12th 2023].

Deleidi, M., Mazzucato, M., Semieniuk, G. (2020). Neither crowding in nor out: Public direct investment mobilising private investment into renewable electricity projects. Energy Policy, 140, 111195.

Heimberger, P., Lichtenberger, A. (2023). RRF 2.0: A Permanent EU Investment Fund in the Context of the Energy Crisis, Climate Change and EU Fiscal Rules. The Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies (wiiw) Policy Report, No. 63. Retrieved from https://wiiw.ac.at/rrf-2-0-a-permanent-eu-investment-fund-in-the-context-of-the-energy-crisis-climate-change-and-eu-fiscal-rules-p-6425.html [last downloaded January 18th 2023].

Pekanov, A., Schratzenstaller, M. (2020). The role of fiscal rules in relation with the green economy. Study requested by the ECON committee (September 2020).

European Commission [EC] (2020). Commission Staff Working Document. Impact Assessment – Stepping up Europe’s 2030 Climate Ambition. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A52020SC0176 [last downloaded on September 21st 2022].

European Commission [EC] (2022). Communication on orientations for a reform of the EU economic governance framework. COM(2022) 583 final.

Wildauer, R., Leitch, S., Kapeller, J. (2020). How to boost the European Green Deal’s scale and ambition. Policy Paper, Foundation of European Progressive Studies / Karl-Renner Institute / Austrian Federal Chamber of Labour, June 2020.

About the article

ISSN 2305-2635

The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Austrian Society of European Politics or the organisation for which the authors are working.

Keywords

investment, EU, Europe, climate change, energy crisis, financing, RRF 2.0

Citation

Heimberger, P., Lichtenberger, A. (2023). A Permanent EU Investment Fund for Tackling the Climate and Energy Crisis. Vienna. ÖGfE Policy Brief, 06’2023