Policy Recommendations

- Aid should go beyond addressing the lack of immediate resources and providing material support or temporary external assistance. Focus needs to be on long-term orientation, political conditionality and capacity building on an institutional level.

- Economic Partnership Agreement partners have some institutional advantages when it comes to trade with the EU and should make full use of those by protecting sensitive sectors within the framework of trade deals.

- Targeted EU assistance for industrialization success stories is crucial, especially since importing back products processed in the EU hurts the same sectors in the domestic market. This could be achieved in the form of sector-specific grants from EU development assistance funds.

Abstract

The narratives in the media with respect to EU external policies and their effects on developing countries generally paint a picture of unequal power dynamics and negative externalities, particularly with respect to international trade and land grabbing. In this Policy Brief, I use trade data to argue that reality is more nuanced and aim to provide a preliminary sketch of the institutional dynamics between the EU and Africa. I focus on agricultural relationships to highlight the interplay between historical path dependencies, colonialism, trade policy and domestic institutions on the EU and African side. While trade is often portrayed in an overly simplified manner as the main factor hindering agricultural development, African countries are often plagued by a long history of extractive institutions, both politically and economically, which lead to a vicious circle of unequally distributed resources, exploitation, insecure human rights and a lack of incentives for innovation. This becomes apparent when examining phenomena such as land-grabbing, which often involves African elites partnering with foreign investors to conclude controversial deals. Overall, this paper aims to highlight the necessity of building institutional capacity, particularly in countries with a long history of extractive institutional continuity, and to underline the importance of state centralisation for agricultural development, so that African partners can fully take advantage of the preferential trade regime with the EU and improve their position with respect to power dynamics.

****************************

Neocolonialism or Balanced Partnership?

The State of Agricultural Trade Between the EU and Africa

While Europe finds itself at a crossroads and seems unable to tackle the challenges of considerable waves of immigration, the African continent too appears to be in flux. The recent creation of the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) at the initiative of the African Union unlocks new potential for recalibrating the continent’s often fraught commercial relations with the EU. The new free trade area would be the world’s largest in terms of members (44 countries have signed the framework, which will be followed by parliamentary ratification) and would cover 1.2 billion people and a GDP of $2.5 trillion, if all 55 potential members join. The initiative is meant to boost intra-African trade by at least 50% via reducing tariffs, eliminating non-tariff barriers, liberalizing services and the movement of people and fostering cooperation. It further aims to support diversification and a change of course away from extractive exports (currently making up 75% of extra-African exports) and towards industrialization[1]. This shift in trade relations has the potential to decisively influence agricultural developments in African countries and recalibrate terms of trade with the EU. Trade in agricultural products between the EU and Africa has been portrayed in the media as problematic in light of issues such as unequal access to markets, EU agricultural subsidies, land grabbing and the impoverishment of native farmers at the hands of cheap European imports flooding African food markets. Nevertheless, the recent events show that there is now more impetus than ever for cooperation. It is thus imperative that more attention is given to sustainable development in this region.

Institutional framework on the EU side

A controversial feature of EU internal policy are the agricultural subsidies. The Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) provides direct payments to farmers, decoupled from production. They are amounting to 72% of the EU farming budget.[2] On average, farmers receive €267 per eligible hectare and may be eligible for additional sources of funding. This effectively amounts to a blanket subsidy for farming, even in the absence of targeted subsidies for specific product categories. Agricultural subsidies have been heavily criticised for their distorting effects and incoherence with development objectives, and have subsequently been reformed until they reached their present form (Matthews, 2008). Nevertheless, some studies show, eliminating subsidies would still have marginal but positive effects on developing countries and their poverty indicators (see Boysen et al, 2016, for a case study on Uganda).

Table 1: Trade balance in million ECU/EURO – SITC 06: Food, drinks and tobacco (Eurostat data, own representation)

In terms of trade, the EU is a net exporter of food, registering a surplus of EUR 2.4 billion in August 2017.[3]

The EU trade institutional structure is multi-layered, sector-specific and consists of various measures. Tariff measures include preferential tariff rates, tariff quotas (in which a specified quantity of a product can be imported at no cost, whilst quantities exceeding the specified amount are subject to a tariff) and “third country duties”, which apply to imports originating in non-EU countries. These are defined in the Combined Nomenclature[4], which provides the legislative structure to implement the Common Customs Tariff. Products are classified by CN code, with each being assigned its respective duty rate. As it is common for the EU legislative process, amendments to the Combined Nomenclature can originate as Commission regulations to be implemented once approved in Parliament and Council, or can be requested by individuals.

In addition to tariff measures, the EU also implements agricultural measures specific to certain sectors, Trade Defence measures in the form of antidumping duties (in the case of products whose price is deemed unfair or violating competition rules) and restrictions on imports and exports, such as veterinary or sanitary controls on food products. In practice, the architecture of EU trade measures means that while tariff liberalisation is often achieved within the framework of EU trade deals, there are numerous other measures, both general (i.e. applying to all categories of goods) and specific to the agricultural sector, that may constitute barriers to trade and limit the access and competitiveness of African imports.

In practice, the architecture of EU trade measures means that while tariff liberalisation is often achieved within the framework of EU trade deals, there are numerous other measures … that may constitute barriers to trade and limit the access and competitiveness of African imports.

The EU often applies preferential tariffs to African countries (ex: 0% on tomatoes from Ghana, while Ghana applies a 20% tariff on EU tomatoes) within the framework of the Generalised Scheme of Preferences (GSP) and, more recently, Economic Partnership Agreements (EPAs). GSP treatment consists of three levels: a general arrangement, a special incentive arrangement for sustainable development and good governance (‘GSP+’) and the EBA (“Everything But Arms”) Initiative. It is a preferential arrangement aiming to contribute to poverty eradication by expanding exports from countries most in need; to promote sustainable development and good governance; and to ensure a better safeguard for the EU’s financial and economic interests[5].

EPAs[6] are regional preferential agreements available to African, Caribbean and Pacific partners under the Cotonou Agreement, that “ensure that account is taken of the vulnerability of the economies of the [partner] region and that the liberalization process incorporates the principles of progressivity, flexibility and asymmetry in favour” of the partner (EU-Ghana EPA, Art. 2). They provide immediate tariff liberalization for imports from the partner countries, as well as duty-free and quota-free access to European markets and flexible Rules of Origin regulations. Financial assistance is also available to ensure cooperation on areas such as sanitary, phytosanitary and product standards. For their part, EPA partners are allowed to restrict market access for EU imports in the case of sensitive products or in order to protect infant industries. The EU has furthermore committed to stop export subsidies on all agricultural products exported to EPA destinations. [7] Nevertheless, barriers to African imports remain in the form of erga omnes rules comprising certifications and licenses, third country duties or non-preferential tariff quotas. For instance, banana imports from the Ivory Coast enjoy tariff-free access to EU markets but are still subjected to a 16% third-country duty.[8]

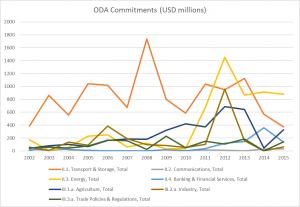

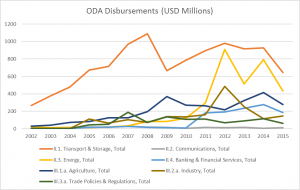

The EU is also offering trade development assistance in the form of the Aid for Trade program as part of Official Development Aid (ODA), financed through the European Development Fund for African, Caribbean and Pacific countries. EU Official Development Aid flows consist of loans and grants that can take the form of commitments (firm written obligation by EU institutions to allocate funds in order to provide resources under specified financial conditions and for specified purposes to the benefit of the recipient country) or disbursements (the placement of resources at the disposal of the recipient, be it a government or an official agency).

In the area of development and cooperation, the Cotonou Agreement[9] (in force for the time period 2000-2020) provides the framework for the EU’s relations with African countries. Besides trade and economic cooperation, it consists of two other pillars: development and political cooperation. Most development programs are financed through the European Development Fund, with African countries also receiving funding from the EU budget. Furthermore, on the 4th of May 2017, the EU launched a strengthened Partnership with Africa, in which agricultural development is specifically mentioned as one of the priority areas.

Developments in Africa

The EU is Africa’s main trade partner, with a share of 35.2% of total trade. 37.5% of African exports go to the EU, and 33.8% of imports originate from the EU. According to Eurostat’s Africa-EU key statistical indicators (2016), the EU has an overall positive balance of trade with Africa, but a deficit for trade in food products, with imports from Africa exceeding exports.

Despite market liberalization, African agricultural factor markets are still subjected to widespread market failures that appear to be structural and unrelated to factors such as geography or gender of the household head (Dilllon & Barrett, 2014). Challenges such as poor infrastructure, insecure property rights over land, limiting regulations that prevent investment in agriculture, lack of access to credit, electricity and modern technologies or limited labour and capital mobility still plague the agricultural sector. Another factor inhibiting growth is the increased proliferation of very small farms due to fragmentation of land in family holdings (as part of inheritance processes), which greatly limits efficiency. Further issues related to market failures and power relations have also been addressed in existing literature, such as land-grabbing activities by foreign nationals, speculative operations involving land and markets that are not accessible to vulnerable demographic categories, such as women or young people. (IFAD Rural Development Report 2016, p. 145-146). Institutional deficiencies in some countries are other explaining factors.

Figure 2: Official Development Aid Flows To African Countries from EU institutions ( OECD CRS Database, own representation)

It thus becomes clear that there is significant potential for the EU to act as a driver of change and a key player in the region, by exporting its corporate values and standards and by enforcing the political conditionality of regional cooperation agreements more strictly.

The development of power dynamics in African agriculture nowadays points towards an intervention vacuum of the European Union. First, historical dependencies and extractive institutions have persisted after decolonization, a situation that becomes apparent with respect to land grabbing, where African state institutions play a key role in facilitating or leading abusive deals. Furthermore, the legality of those deals seems enshrined in national legislative frameworks, which points out the necessity of legal reforms guaranteeing human rights. Additionally, the presence of non-EU investors sketches a picture of shifting spheres of influence and a decreasing importance of the EU. It thus becomes clear that there is significant potential for the EU to act as a driver of change and a key player in the region, by exporting its corporate values and standards and by enforcing the political conditionality of regional cooperation agreements more strictly. With respect to the former, the binding European Parliament resolution on conflict minerals is a first step. Furthermore, EU trade agreements mention CSR standards, which are nevertheless criticized for not being properly enforced or sufficient to mitigate the effects of land grabbing (Borras and Franco, 2010b).

Policy Recommendations

Market failures in Africa are structural and connected to poor governance and a lack of functioning institutions (Bräutigam and Knack, 2004). This suggests that aid should go beyond addressing the lack of tangible resources and providing material support or temporary external assistance (as is often the case with European experts being sent in to provide technical assistance). Focus needs to be placed on long-term orientation and capacity building on an institutional level.

Following a decline in the role and capacities of the state under neoliberalism, NGOs have witnessed an increasingly high usage of their services in development programs in Africa. Nevertheless, non-state actors face limitations stemming from their very nature, such as the often small size of the projects, limited institutional capacity, limited awareness of the sociocultural milieu in which they operate or the problematic notion of relying on private actors to fix society-wide problems, thus increasingly weakening and bypassing the state. NGO developmental solutions and outcomes are inherently small-scale and short-term, and may not be replicable or efficient on a national level, which raises the necessity of state institutional development and closer cooperation with governmental actors. (Nega & Schneider, 2014)

The EU could contribute to the creation of sound, inclusive political and economic institutions within the framework of the Cotonou Agreement, as part of the Political Cooperation Pillar, or using the GSP+ framework. Political conditionality is an important tool, rendered even more credible and thus effective by the current geopolitical context and the increased global focus on democracy and human rights (Dunning, 2004). The focus should thus lie on the proper enforcement of conditionality, in order to create clear incentives for reform.

On the African side, EPA partners have some institutional advantages when it comes to trade with the EU and should make full use of EPA advantages by protecting sensitive sectors. For instance, the interim agreement with West Africa includes a chapter on trade defence with bilateral safeguards allowing each party to reintroduce duties or quotas if imports of the other party disturb or threaten to disturb their economy; there are also safeguards for food security or the protection of infant industry[10]. Ghana, for example, has chosen not to liberalise some sectors deemed sensitive, such as sugar, chicken, tomatoes or tobacco, which will continue to be taxed at the regular ECOWAS tariff rate.[11]

Targeted EU assistance for industrialization success stories such as the development of the textile industry in Madagascar or cocoa processing in Ghana and Cote d’Ivoire[12] is crucial, especially since importing back products processed in the EU hurts the same sectors in the domestic market. This could be achieved in the form of sector-specific grants from EU development assistance funds, so as to provide funding for incentive schemes such as tax credits. Given that the share of ODA funds allocated to industry is rather low, there is potential for redistribution here.

Overall, this Policy Brief has highlighted the need for a recalibration of EU policy and more differentiated narratives with respect to agricultural relations between the EU and Africa. While trade is often portrayed in an overly simplified manner as the main factor hindering agricultural development, reality is more nuanced. African countries are often plagued by a long history of extractive institutions, both politically and economically, which lead to a vicious cycle of unequally distributed resources, exploitation, insecure human rights and a lack of incentives for innovation. EU external policy should focus on building institutional capacity and strengthening state centralization, so that African partners can fully take advantage of the preferential trade regime with the EU and improve their position with respect to power dynamics.

[1] African Continental Free Trade Area Q&A, compiled by the African Trade Policy Centre (ATPC)

of the Economic Commission for Africa (ECA) in association with the African Union Commission. Retrieved at https://au.int/sites/default/files/documents/33984-doc-qa_cfta_en_rev15march.pdf

[2] European Commission, DG AGRI homepage: https://ec.europa.eu/agriculture/direct-support/direct-payments_en

[3] European Commission (2017). Monitoring EU Agri-Food Trade: Development until August 2017. Retrieved at https://ec.europa.eu/agriculture/sites/agriculture/files/trade-analysis/monitoring-agri-food-trade/2017-08_en.pdf

[4] Full text of the Combined Nomenclature can be retrieved at http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=OJ:L:2016:294:FULL&from=EN

[5] European Commission. (2011). Impact Assessment Accompanying the Proposal for a Regulation on Applying

a Scheme of Generalised Tariff Preferences (SEC (2011) 536 final). Available at: http://ec.europa.eu/smartregulation/impact/ia_carried_out/docs/ia_2011/sec_2011_0536_en.pdf, 18-19

[6] EPAs are currently enforced with the following groups of countries: West Africa (Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana), Central Africa (Cameroon), Eastern and Southern Africa (Mauritius, Madagascar, Seychelles, Zimbabwe), and the Southern Africa Development Community (SADC) (Botswana, Lesotho, Namibia, South Africa, Swaziland). A complete overview can be retrieved at http://trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/docs/2009/september/tradoc_144912.pdf

[7] European Commission. Putting Partnership Into Practice. EPAs between the EU and ACP countries. Retrieved at http://trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/docs/2017/october/tradoc_156340.pdf

[8] Calculations on tariff and duty rates retrieved at http://ec.europa.eu/taxation_customs/dds2/taric/measures.jsp?Lang=en&SimDate=20171024&Area=CI&Taric=0803&LangDescr=en

[9] The full text of the Cotonou Agreement can be retrieved at http://www.europarl.europa.eu/intcoop/acp/03_01/pdf/mn3012634_en.pdf

[10] Chapter 2, Art. 22 and 23. Full text of the agreement available at http://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-13370-2014-INIT/en/pdf

[11] European Commission, DG TRADE. Interim EPA Between Ghana and the EU Factsheet, 2017, available at http://trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/docs/2017/february/tradoc_155314.pdf

[12] Putting Partnerships Into Practice: EU-EPAs Brochure available at http://trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/docs/2017/october/tradoc_156340.pdf

- Berhanu Nega & Geoffrey Schneider (2014) NGOs, the State, and Development in Africa, Review of Social Economy, 72:4, 485-503

- Boysen, O., Jensen, H. G., & Matthews, A. (2016). Impact of EU agricultural policy on developing countries: A Uganda case study. The Journal of International Trade & Economic Development, 25(3), 377-402.

- Bräutigam, D. A., & Knack, S. (2004). Foreign aid, institutions, and governance in sub-Saharan Africa. Economic development and cultural change, 52(2), 255-285.

- Dillon, Brian; Barrett, Christopher B.. 2014. Agricultural factor markets in Sub-Saharan Africa : an updated view with formal tests for market failure. Policy Research working paper ; no. WPS 7117. Washington, DC: World Bank Group.

- Dunning, T. (2004). Conditioning the effects of aid: Cold War politics, donor credibility, and democracy in Africa. International Organization, 58(2), 409-423.

- EUROSTAT, The European Union and the African Union: A statistical portrait (2016 edition). Retrieved at https://www.tralac.org/images/docs/11346/the-european-union-and-african-union-a-statistical-portrait-2016-edition-eurostat.pdf

- Franco, J., & Borras, J. (2010b). From threat to opportunity? Problems with the idea of a “code of conduct” for land-grabbing. Yale Human Rights & Development Law Journal.

- IFAD. Rural Development Report 2016. Retrieved at https://www.ifad.org/documents/30600024/30604583/RDR_WEB.pdf/c734d0c4-fbb1-4507-9b4b-6c432c6f38c3

- Matthews, A. (2008). The European Union’s common agricultural policy and developing countries: The struggle for coherence. European Integration, 30(3), 381-399.

ISSN 2305-2635

The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Austrian Society of European Politics or the organisation for which the author works.

Key words

development economics, international trade, EU Neighborhood Policy, institutions

Citation

Lungu, I. (2018). Neocolonialism or Balanced Partnership? The State of Agricultural Trade Between the EU and Africa. Vienna. ÖGfE Policy Brief, 15’2018

Hinweis:

Zu diesem Policy Brief ist auch ein Gastkommentar in der Wiener Zeitung erschienen.