Policy Recommendations

- More debates

- Step out of the bubbles

- Go offline

Abstract

In a research on populist attitudes in Hungary and Poland, we found that “tribalism” describes the phenomenon way better. While we started to study populist attitudes, we found something more dangerous and malevolent: the combination of Manichean, black and white narratives that divide the world between good and evil and authoritarianism that puts trust in a strong leader, which makes a dangerous combination. We labelled it tribalism: a mentality which is about rallying around the leader of the tribe and fighting against the other tribe with every tools possible.

What to do against tribalism?

- More debates. Debate culture is traditionally weak in both Hungary and Poland, and it has been weakened further in recent years. This provides a fertile ground for tribalism and polarisation.

- Stepping out of bubbles. Good debates can be organized only if the participants are willing to step out of their comfort zone and get out of their bubbles. Debates outside the capital are especially important. The events we organized were very important for these groups as well to get recognized by their local authorities and gain more visibility among the inhabitants.

- Bridging the ‘populist gap’. The most successful events are the ones where the speaker-audience divide can be diminished, creating an environment where status differences does not determine the discussion.

- Going offline. As Timothy Snyder puts it: “Within the two-dimensional internet world, new collectivities have arisen, invisible by the light of day—tribes with distinct worldviews, beholden to manipulations.” To counter this tendency, there is a need for more debates in the offline space. More discussions outside the online platforms are necessary for reducing the echo chamber effect: the driver of tribalism.

****************************

How to challenge the Tribalist Zeitgeist?

How to challenge tribalism?[1]

report summary

With Polish and Hungarian colleagues the Political Capital Policy Research and Consulting Institute started a research project two years ago. In this study, we wanted to examine how populist politicians in power can do the magic trick: mobilizing their electorate with anti-elite messages while being the political elite themselves? How can they keep their voter bases happy and who is resonating with their way of governance? And what can be the broader, long-term impact of their policies?

We chose these two countries for our research for several reasons:

First, in these countries we have populists in government. And still, despite the “populist Zeitgeist”, countries, where authoritarian populists are exercising the executive power, are still rather the exception than the rule. Beside these two, Italy and Austria are notable examples as well. And, of course, the United States.

Second, Hungary and Poland are the early birds of this populist era. Populists in these Central Eastern European countries were elected before it was cool: eight years ago in Hungary[2] and three years ago in Poland. Based on these experiences, the assumption that populism can only be successful in opposition – and not in government – certainly has to be overcome. “Populist establishments” can be highly successful in delivering results at the policy level, and in transforming the institutions – or even, building up new institutions[3]. Unlike in the early 21st century, when populists in Central Eastern Europe rather had to accept the rules of the game of the international establishment, and populists lost the power quite easily (eg. first term of Viktor Orbán, Jarosław Kaczińsky, and PiS – Prawo I Sprawiedliwosčć / Law and Justice), populism these days can deliver on their promises and keep its popularity.

Third, Hungarian and Polish populism have a lot in common: the sense of victimhood, feeling of limited sovereignty, a peripheral position within the European Union and a negative perception of superpowers in the West and in the East – especially in Poland. These sentiments are widely exploited by populists in both countries. But of course we do see these patterns in a different constellation in Western Europe as well.

Fourth, in both countries, which are mostly ethnically homogeneous, politicians are exploiting “platonic xenophobia” – anti-immigration sentiment without immigrants. The ratio of Muslim immigrants are negligible, but still, they are the most important public enemy.

And fifth: both, Orbán and Kaczińsky are using textbook examples of populist rhetoric: “Vox Populi, vox Dei” – this is how Jarosław Kaczińsky summarized his populist political credo a few years ago, referring to the Latin phrase meaning “Voice of the people, the voice of God”. Viktor Orbán made the message that his government is the sole representative of the will of the people even more concrete after a manipulative, government-organized referendum: “It will be small consolation that the people of Europe will not forgive the leaders who completely changed Europe without first asking its people. Let us be proud of the fact that we are the only country in the European Union which has asked people whether or not they want mass immigration.”

Tribalism, not populism

In our representative research we conducted on Poland and Hungary, we focused on “populist attitudes,” and not the support for populist parties – although we also measured party preferences.

We labelled it tribalism: a mentality which is about rallying around the leader of the tribe and fighting against the other tribe with every tools possible.

But finally, what we found is something different and more malevolent than what the term “populism” suggests. While we started to study populist attitudes, we found something more dangerous and malevolent: the combination of Manichean, black and white narratives that divide the world between good and evil, and authoritarianism that puts trust in a strong leader, which makes a dangerous combination. We labelled it tribalism: a mentality which is about rallying around the leader of the tribe and fighting against the other tribe with every tools possible. We found that tribalists are more likely to support political violence as a tool and are also more likely to reject political pluralism. Tribalism is beyond populism: tribalists do not share democratic attitudes, they are authoritarian, politically intolerant and, to a certain extent, elitist. The proportion of tribalists is 10% in Hungary and 15% in Poland. Tribalists are overrepresented on the governmental side, especially in Hungary: 59% of tribalists would vote for Fidesz (Magyar Polgári Szövetség / Hungarian Civic Alliance). While they form a minority of the populations, this is rather indicative of the nature of our times, where, as Cas Mudde[4] writes, populists paint themselves as the silent majority while being the loud minority.

Voters of populist parties did not follow the political science descriptions of populism in their attitudes in at least two ways.

A significant portion of these societies support a strong leader instead of elected politicians.

First people-centrism (a reference to the will of the people as the final source of legitimacy) was found to be weak among the supporters of parties claiming to be the sole representative of “the people”— among voters of PiS and Fidesz. But at the same time, authoritarian attitudes putting the trust in the leaders instead of the collective will of the people was found to be strong. A significant portion of these societies support a strong leader instead of elected politicians. This ratio is higher in Poland (35%) than in Hungary (26%), but in both countries, stronger in the governmental parties.

According to our research, negative sentiments towards the domestic elite are stronger among supporters of opposition parties than among supporters of governing parties.

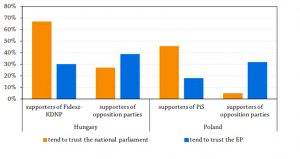

Second, voters of populist right-wing governmental parties do not dislike the elite – just the very opposite. According to our research, negative sentiments towards the domestic elite are stronger among supporters of opposition parties than among supporters of governing parties. Their parties are THE elite. Of course, we see a certain anti-elitism, but populists in government and in opposition see the elite elsewhere. While populists in opposition are concerned with the national elite (and mainly the government), populists in government rather channel social discontent towards international elites (and their domestic allies). If the anti-elitist opposition party becomes the elite itself, the voter base seems to easily adapt to this new situation. Pro-government voters in Poland and Hungary see the national parliament as trustworthy, but do not regard the European Parliament the same way[5]. For opposition voters, it is the other way around (see Figure 1).

Figure 1

Circus, not the bread

Tribalism mobilizes, unites and divides using the concept of the nation and not of class. Tribalism is about identity, and not about money.

In the end we might destroy a myth, but voters of populist parties are not populist. In addition, we could destroy another one as well: that this whole thing is all about the pockets, money and redistribution. We found that in Poland and Hungary, socio-demographic indicators predict receptivity to populism and tribalism very poorly. Party preference trumps all other factors. In our opinion, it reveals a more general tendency. Contrary to common wisdom, right-wing populism is much more about the circus than about the bread. Inequality and socio-economic deprivation, while definitely creating fertile grounds for the rise of authoritarian populism, fail to explain its political success. Today’s main right-wing populists are not exploiting economic populism, it rather targets identity-based fears and nationalist sentiments. Tribalism mobilizes, unites and divides using the concept of the nation and not of class. Tribalism is about identity, and not about money.

Where tribalism triumphs, it has an impact on the whole political landscape.

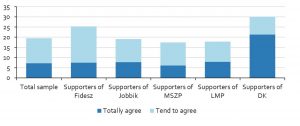

But also, we found that some facets of tribalism are all around the political spectrum and cannot be localized only in these countries: not only the supporters of populist parties are open to populist narratives. We have found left-wing and liberal parties with strong black and white views on politics similar to the electorate of the two governing parties. In Hungary, the voters of the social democratic party Democratic Coalition (belonging to the Socialists & Democrats group / S&D) and in

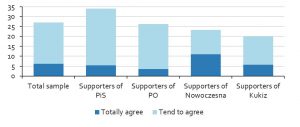

Poland, voters of the liberal party Nowoczesna (belonging to The Alliance for Liberals and Democrats for Europe Party / ALDE) were found to share the fight against the good and the evil the same way as voters of Fidesz and Law and Justice. Where tribalism triumphs, it has an impact on the whole political landscape.

Figure 2: Manichaean way of thinking among the supporters of Hungarian political parties (%, level of agreement with the statement: “You can tell if a person is good or bad if you know their politics”.)[6]

Figure 3: Manichaean way of thinking among the supporters of Polish political parties (%, level of agreement with the statement: “You can tell if a person is good or bad if you know their politics”.)[7]

What to do with tribalism?

Our suggestion would be, based on the analysis above, that the term “populism” should be ignored in order to explain the phenomena that we are facing today, and the term “tribalism” describes this phenomenon in a more accurate form.

Poland and Hungary are good showcases. In these countries, leaders of the tribes want to benefit from fuelling tribal views instead of reducing them, as they have a lot to gain from increasing polarisation.

Tribalism, fuelled from above, is a Zeitgeist, and the new norm. Still, it can be especially dangerous in Central and Eastern Europe, where democratic institutions are young, fragile and democratic norms are weaker – therefore, “tribalist establishments” can transform and rewrite the whole socio-political setting. Transgressions of democratic norms such as occupation of the institutions and corruption are becoming acceptable tools or sources of “tribal good” instead of public good in a tribal war. Poland and Hungary are good showcases. In these countries, leaders of the tribes want to benefit from fuelling tribal views instead of reducing them, as they have a lot to gain from increasing polarisation.

What to do against tribalism? The short, cynical response could be: accept it as the new normal. But if we want to do something, we can build on some of our experiences. With our partners we organized 14 discussions in small and middle-sized towns in Poland and Hungary. Our aim was to talk about controversial issues and understand how to address tribalism on the local and regional level. The methods we found that can potentially mitigate tribalism are the following:

- More debates. Debate culture is traditionally weak in both Hungary and Poland, and it has been weakened further in the recent years. This provides a fertile ground for tribalism and polarisation.

- Stepping out of bubbles. Good debates can be organized only if the participants are willing to step out of their comfort zone and get out of their bubbles. Debates outside the capital are especially important. The events we organized were very important for these groups as well to get recognized by their local authorities and gain more visibility among the inhabitants.

- Bridging the ‘populist gap’. The most successful events are the ones where the speaker-audience divide can be diminished, creating an environment where status differences does not determine the discussion.

- Going offline. As Timothy Snyder puts it:[8] “Within the two-dimensional internet world, new collectivities have arisen, invisible by the light of day—tribes with distinct worldviews, beholden to manipulations.” To counter this tendency, there is a need for more debates in the offline space. More discussions outside the online platforms help reducing the echo chamber effect: the driver of tribalism.

[1] The project consisted of two parts: extensive analysis and targeted outreach. The comprehensive research incorporated desktop research, a representative survey and qualitative interviews with the aim of identifying socio-demographic factors and other possible contexts and correlations concerning the support of populism. Simultaneously, the activity-focused component involved the work of grassroots community partners, we worked with 15 organisations altogether.

[2] Disregarding the first term of Viktor Orbán.

[3] Zsolt, Enyedi: understanding the rise of populist establishments. http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/europpblog/2018/07/04/understanding-the-rise-of-the-populist-establishment/

[4] https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2018/sep/06/populists-silent-majority-loud-minority

[5] According to European Social Survey data.

[6] Fidesz: governmental party (populist right, EPP), Jobbik: opposition party, far-right (NA), MSZP: opposition, center-left (S&D), LMP: opposition, green (Greens), DK: opposition, center-left (S&D), the party of ex-PM Ferenc Gyurcsány

[7] PiS: governmental party, populist right (ECR), PO: opposition party, center-right (EPP). Nowoczesna: opposition party, liberal (ALDE). Kukiz 15: opposition, far-right

[8] Snyder, Timothy. On tyranny: Twenty lessons from the twentieth century. Tim Duggan Books, 2017.

The full report of the study: http://www.politicalcapital.hu/pc-admin/source/documents/pc_beyond_populism_study_20180731.pdf

ISSN 2305-2635

The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Austrian Society of European Politics or the organisation for which the author works.

Keywords

tribalism, populism, Poland, Hungary

Citation

Krekó, P., Juhász, A., Molnár, C. (2019). How to challenge the Tribalist Zeitgeist? Vienna. ÖGfE Policy Brief, 01’2019