Policy Recommendations

- EU Member States should seize the unique opportunity offered by the Brexit for a fundamental reform of EU expenditures to create more European value added with a focus on sustainability.

- EU expenditures should only target policy areas in which Member States’ un-coordinated actions will be insufficient or policy areas in which common European interests are at stake.

- Sustainability-oriented tax-based own resources could act as a catalyst to secure the agreement of net contributor countries to uphold the current expenditure level in exchange for far-reaching reforms of the expenditure structure.

Abstract

The current discussion about the EU budget after the Brexit strongly focuses on its future volume and the effects on national contributions. At the same time, however, the Brexit offers a unique opportunity for fundamental sustainability-oriented structural reforms of the EU budget. To create more European value added with a focus on sustainability, overall agricultural expenditures should be reduced and greened; cohesion funds should be shifted more effectively from „richer“ to „poorer“ Member States and coupled more strongly to climate and employment goals as well as a pro-active migration and integration policy; and expenditures for sustainability-oriented research and infrastructure should be increased. By replacing national EU contributions with sustainability-oriented tax-based own resources like an EU-wide carbon-based flight ticket tax, a net wealth tax, a financial transactions tax and a Common (Consolidated) Corporate Tax Base, the EU system of own resources can support central EU goals. Whether the Brexit is really able to support future-oriented reforms of the EU budget will eventually depend on how Member States will adapt to the expected revenue shortfall of € 10 billion annually: by increasing national contributions or introducing additional revenue sources; by expenditure cuts; or by a combination of these two options. Substituting a substantial share of national contributions by sustainability-oriented tax-based own resources may act as a catalyst to secure the agreement of net contributor countries to uphold the current expenditure level in exchange for far-reaching reforms of the expenditure structure.

****************************

The Brexit as opportunity for a sustainability-oriented reform of the EU budget[1]

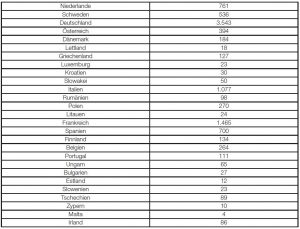

The current debate about the implications of the imminent Brexit for the EU budget, which is led in the run-up to the upcoming negotiations about the next Multi-annual Financial Framework (MFF) of the EU for the period 2021 to 2027, almost exclusively focuses on a few figures: in particular on the future volume of the EU budget and on the national contributions EU Member States will have to expect after the United Kingdom, as the second largest contributor to the EU budget, will have left the EU. Particularly the ten net contributing Member States are gearing themselves up for a defensive battle against increasing contributions to the EU budget. Indeed, according to current estimations of Haas/Rubio (2017), the expected increases would not be insignificant. Germany, for instance, would have to pay further net contributions of up to 3,543 million euros, France of up to 1,465 million euros and Austria of up to 394 million euros.

Graph 1: Implications of the Brexit on the net contributions of the EU-countries, in million euros, annually

Source: Haas/Rubio (2017); “Der Standard“, 25/26 March 2017.

However, this debate exactly follows the argumentation pattern well-known from past negotiations about the MFF: when determining the benefits from the EU budget (which currently amounts to one percent of the EU’s gross national income), Member States primarily consider their respective net positions, i.e. the difference between payments into the EU budget and transfers received out of it, while indirect benefits from membership in the Single Market are almost completely neglected.

This “juste-retour”-logic prevents Member States from seeing the Brexit shock as an opportunity to fundamentally reform the structure of the EU’s expenditures and revenues.

This “juste-retour”-logic prevents Member States from seeing the Brexit shock as an opportunity to fundamentally reform the structure of the EU’s expenditures and revenues: an opportunity most prominently stressed recently by the Monti-Report on the future of EU funding released in the beginning of 2017 (High Level Group on Own Resources, 2016).

The EU is facing a number of important long-term challenges, which range from the recent and imminent rounds of enlargement over structural problems of the southern countries, unprecedented unemployment and youth unemployment, climate change and energy transition, demographic change, increasing inequality of income and wealth and risk of poverty to refugee migration. The current structure of the EU budget – expenditures as well as the revenue system – is in no way adequate to cope with these challenges.

As a general principle, EU expenditures should only target policy areas in which Member States’ un-coordinated actions will be insufficient due to free riding, coordination problems and cross-border issues; or policy areas in which common European interests are at stake. In particular, the EU needs to provide those public goods that cannot be secured at Member State level alone as their benefits transgress national borders. The EU budget in its current structure provides too little “true” European public goods, and thus too little European added value. This is one of the reasons why net contributor countries despite increasing European challenges are more and more reluctant to top up or even to only uphold the current volume of the EU budget, and why a growing proportion of EU citizens do not perceive a direct benefit of the EU budget in their own lives.

The EU budget in its current structure provides too little “true” European public goods, and thus too little European added value.

The current MFF dedicates 13 percent of its overall volume to competitiveness and infrastructure (including research expenditures), 34 percent to cohesion policy, and another 39 percent to agricultural policy. To be able to support a more dynamic, socially inclusive and environmentally sustainable growth and development path for the EU, as anchored in the Europe 2020 strategy or in the UN 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (European Commission, 2016), EU expenditures need to be restructured considerably (Schratzenstaller, 2013). At least four gaps should be addressed to strengthen sustainability-orientation of EU expenditures:

Firstly, expenditures for agricultural policy today are mainly preserving existing, conventional production structures within the “first pillar”. A large share of agricultural subsidies is granted to large agricultural units, prioritising conventional agriculture. For the smaller farms, instead of actively supporting a transition on their part to environmentally sustainable production, a large part of income support is granted unconditionally. The more sustainability-oriented “second pillar” of agricultural expenditures, which could actively support organic farming and rural employment in smaller units, currently amounts to less than one quarter of overall agricultural spending only.

Secondly, structural and cohesion policy focuses too strongly on a traditional infrastructure policy favouring material (large-scale) infrastructure. As “richer” Member States are benefiting from subsidies within agricultural and cohesion policy to a substantial extent, funds are not redistributed to the “poorer” member states in a focused and targeted way.

Thirdly, expenditures for research and infrastructure still account for a comparatively small fraction of overall expenditures. A very small fraction of R&D expenditures actively supports a socio-ecological transition in the EU: for example, only 5% of overall research expenditures are dedicated to green R&D.

Fourthly, too little funding is made available to make a substantial EU contribution to the goals of an internationally coordinated approach to the mitigation of the world-wide refugee crisis as defined at the Summit for Refugees and Migrants hosted by the last annual UN General Assembly in September 2016 in New York[2]: to allocate more funds to humanitarian assistance; to set up functioning resettlement programs or alternative legal structures to get countries to admit more refugees; and to implement integration policies enabling refugees’ to education and legal work.

European value added with a focus on sustainability can be created by:

- Reducing overall expenditures for agricultural policy; reinforcing the “greening” of direct payments to farmers within the “first pillar” of agricultural policy and the shift of agricultural expenditures to the “second pillar” supporting environmental and employment goals;

- Shifting cohesion funds from “richer” towards “poorer” Member States and coupling them more strongly with climate goals and employment goals as well as a pro-active migration and integration policy;

- Increasing expenditures for research and innovation, with a specific focus on environmentally and socially relevant aspects (mission-oriented research) and increasing expenditures for sustainability-oriented infrastructure, with a specific focus on Trans-European Networks (particularly railway networks).

Along with substantial reforms in EU expenditures, the EU system of own resources needs to be overhauled fundamentally.

Along with substantial reforms in EU expenditures, the EU system of own resources needs to be overhauled fundamentally. It is true that the current EU system of own resources has certain merits: It provides steady, predictable and reliable revenues; it guarantees a balanced budget; it results in a “fair” distribution of the financial burden across Member States; and it is based on the subsidiarity principle as Member States can decide freely about the distribution of the financial burden among individual taxpayers (Schratzenstaller/Nerudová, 2017). Nonetheless, the current financing system has been attracting various criticisms over the last decades (Schratzenstaller/Krenek/Nerudová/Dobranschi, 2016[3]). From a sustainability perspective, the most important point of criticism refers to the fact that the own resources system does not support at all the aforementioned Europe 2020 Strategy and the Sustainable Development Goals (Schratzenstaller/Krenek/Nerudová/Dobranschi, 2017). Against this background, sustainability-oriented tax-based own resources partially substituting Member States’ national contributions can strengthen the contribution of the EU system of own resources to central EU policies (Schratzenstaller, 2017). Candidates for tax-based own resources which are currently analysed in the Horizon 2020 EU project “FairTax”[4] are an EU-wide carbon-based flight ticket tax (Krenek/Schratzenstaller, 2016), a net wealth tax (Krenek/Schratzenstaller, 2017), a financial transactions tax (Solilová/Nerudová/Dobranschi, 2016) or a common (consolidated) corporate tax base (C(C)CTB) (Nerudová/Solilová/Dobranschi, 2016). Most of these options for tax-based own resources are also addressed in the Monti Report (High Level Group on Own Resources, 2016).

The Brexit can be expected to promote future-oriented reforms of the EU budget directly via several channels.

How realistic is the implementation of such reform proposals in the current political-economic context of the European Union? On the one hand, the Brexit can be expected to promote future-oriented reforms of the EU budget directly via several channels: First of all, because the United Kingdom is one of the most vehement opponents of tax coordination on the EU level. Therefore its exit from the EU should make the introduction of tax-based own resources (for example the financial transactions tax strictly rejected by the United Kingdom), but also other reforms in the area of taxation less controversial among the remaining EU Member States. Secondly, because the United Kingdom is one of the fiercest proponents of the net contributor position, focusing mainly on the difference between payments into the EU budget and transfers received out of it instead of the European value added of EU expenditures. Thirdly, and this is related to the preceding point, the rebate for the United Kingdom will be no longer necessary, so that there is a good chance that the accompanying correction mechanisms (the rebate from the rebate for several net contributing countries) can be abolished at last (High Level Group on Own Resources, 2016). Indirect support may be provided by growing awareness at Member State level that the EU budget needs to deliver more value added for European citizens to prevent further acceleration of exit movements in other EU Member States. This might enhance openness and willingness of Member States to agree to expenditure reforms towards European value added. And to accept reforms on the revenue side, in particular to consider certain tax-based own resources, and especially those that have some integrative power because they are appealing for many EU citizens (e.g. a financial transactions tax).

On the other hand, the Brexit bears the danger of exacerbating the net contributor debate at least in the short run, which may lead to demands for cuts in the overall volume of the EU budget and/or new rebates for net contributors (Haas/Rubio, 2017). And the Brexit might delay discussions and decisions on reforms within the EU budget, depending on the progress in the ongoing negotiations about the “divorce bill” and the future relationships between the United Kingdom and the EU.

Ultimately it will depend on how EU Member States decide to adjust to the expected shortfall of about € 10 billion annually caused by the Brexit: by increasing national contributions or introducing other additional revenue sources; by cutting expenditures; or by some combination of these two options (Haas/Rubio, 2017). Substituting a substantial share of national contributions by sustainability-oriented tax-based own resources may act as a catalyst to secure net contributors’ agreement to maintain the current spending level in exchange for a far-reaching reform of EU expenditures.

[1] The author thanks Michael Landesmann, Sandor Richter and Tamás Szemlér for an interesting discussion at a WIIW panel discussion on the Post-2020 Multi-annual Financial Framework of the EU on March 27, 2017, on which this contribution is based.

[2] https://refugeesmigrants.un.org/summit

[3] http://umu.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:934128/FULLTEXT01.pdf

[4] www.fair-tax.eu

- European Commission. 2016. Next Steps for a Sustainable European Future. COM(2016) 739 final. Strasbourg: European Commission.

- Haas, Jörg, Rubio, Eulalia. 2017. Brexit and the EU Budget: Threat or Opportunity? Jacques Delors Institute/Bertelsmann-Stiftung Policy Paper 183.

- High Level Group on Own Resources. 2016. Future Financing of the EU. Brussels: High Level Group on Own Resources.

- Krenek, Alexander and Schratzenstaller, Margit. 2017. Sustainability-oriented EU Taxes: A European Net Wealth Tax. In Caracciolo, Barbara, Cheuvart, Charline, Dragomirescu-Gaina, Catalin, Gonzales Del Pino, Silvia, Mufafchieva, Radostina, and Ntousas, Vassilis (eds.). Progressive Lab for Sustainable Development: From Vision to Action. Brussels: FEPS, SOLIDAR, Group of the Progressive Alliance of the Socialist and Democrats in the European Parliament. Forthcoming.

- Krenek, Alexander, and Schratzenstaller, Margit. 2016. Sustainability-oriented EU Taxes: The Example of a European Carbon-based Flight Ticket Tax. FairTax Working Paper 1.

- Nerudová, Danuše, Solilová, Veronika, and Dobranschi, Marian. 2016. Sustainability-oriented Future EU Funding: A C(C)CTB. FairTax Working Paper 4.

- Schratzenstaller, Margit. 2017. Defizite im EU-Eigenmittelsystem. Ifo Schnelldienst 70(6): 15-17.

- Schratzenstaller, Margit. 2013. The EU Own Resources System – Reform Needs and Options. Intereconomics 48(5): 303-313.

- Schratzenstaller, Margit, Krenek, Alexander, Nerudová, Danuse, Dobranschi, Marian. 2017. EU Taxes for the EU Budget in the Light of Sustainability Orientation – a Survey, Journal of Economics and Statistics (i.E.)

- Schratzenstaller, Margit, Krenek, Alexander, Nerudová, Danuše, and Dobranschi, Marian. 2016. EU Taxes as Genuine Own Resource to Finance the EU Budget: Pros, Cons and Sustainability-oriented Criteria to Evaluate Potential Tax Candidates. FairTax Working Paper 3.

- Schratzenstaller, Margit, Nerudová, Danuse, Tax-based Own Resources for the EU. Euractiv Guest Blog, January 24, 2017.

- Solilová, Veronika, Nerudová, Danuše, and Dobranschi, Marian. 2016. Sustainability-oriented Future EU Funding: A Financial Transaction Tax. FairTax Working Paper 5.

ISSN 2305-2635

The views expressed in this publication are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Austrian Society of European Politics or the organisation for which the author works.

Keywords

EU budget, tax-based own resources, EU system of own resources, sustainability, Europe 2020 strategy, Brexit

Citation

Schratzenstaller, M. (2017). The Brexit as opportunity for a sustainability-oriented reform of the EU budget. Vienna. ÖGfE Policy Brief, 09a’2017