Policy Recommendations

- The European support for an African Continental Free Trade Area must be targeted to the partner’s needs and focused on facilitating the start of trade in goods.

- The EU still needs to overcome historical mistrust and be aware that African integration may take on a different trajectory than the one the EU has historically followed. The goal should not be to replicate the EU model, but rather to provide an alternative path of African-led regional economic integration.

- Programmes regarding infrastructure development and industrialisation will be particularly relevant for the start of trade and COVID-19 mitigation.

Abstract

The African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) is an exceptionally ambitious project of Pan-African integration. Eliminating tariffs on intra-African imports is, however, not enough. Key issues such as non-tariff barriers, infrastructure and industrialisation need to be addressed for the agreement to deliver on its promises. The risk is that the political momentum will wane, as African Union Member States attempt to mitigate the impact of COVID-19. As countries progressively liberalise trade by 2030, implementation of the agreement remains the biggest challenge of the AfCFTA. Currently, the conclusion of negotiations has been hindered by COVID-19, and the start of trade under the AfCFTA trade regime has been delayed for January 2021. To help meet this target, the EU, historically one of the first supporters of the AfCFTA, needs to intensify and coordinate support targeted at finalising Phase I negotiations and focus on implementation of the agreement.

****************************

The African Continental Free Trade Area: The Role of EU Support for Africa’s Historic Trade Agreement

AfCFTA: State of Play

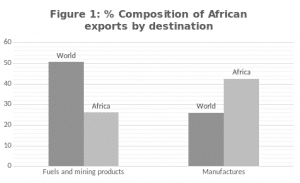

Exports within Africa make up only 17% of the continent’s total exports: the lowest proportion for any region in the world. However, intra-African trade has more value-added: when African countries trade among themselves, their trade has a higher proportion of manufactured products. This reason, as well as the decades-long ambition towards pan-African integration, led to the creation of the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA). It is considered an unprecedented display of African unity and one of the flagship projects of the African Union’s (AU) Agenda 2063: The Africa We Want[1]. If implemented, the agreement would significantly boost intra-African trade, but also strengthen Africa’s negotiating position as a unified trade bloc vis-à-vis other trade partners. Nevertheless, the road to finalising and implementing the AfCFTA is long, and at times rocky.

Source: WTO data (2017), own calculations

Member States have agreed to liberalise 90% of tariff lines. The agreed timeframe for achieving this is 10 years for Least Developed Countries (LDCs) and 5 years for non-LDCs. Developing economies must liberalise sensitive products over 10 years, while LDCs have 13 years over which to liberalise.

Currently, 36 countries out of the African Union’s 55 Member States have ratified the agreement.

Where does the AfCFTA stand? Currently, 36 countries out of the AU’s 55 Member States have ratified the agreement[2]. If all 55 Member States join the AfCFTA, it will be the world’s largest free trade agreement in terms of number of signatories since the creation of the WTO. It will also encompass a market with a population of 1.3 billion people and combined GDP of 2.3 trillion USD. Phase I negotiations on trade in goods and trade in services are not yet finalised. Thirteen countries submitted tariff liberalisation offers for 90% of tariff lines, whilst regional customs unions[3] such as the Communauté Économique et Monétaire de l’Afrique Centrale (CEMAC), Southern African Customs Union (SACU), East African Community (EAC) and Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) have indicated their readiness to submit their offers soon.

The COVID-19 pandemic led to significant delays in the negotiating process, as well as a delay in the start of trade, under the AfCFTA regime, originally planned for July 2020.

Besides trade in goods, the AfCFTA will also liberalise trade in services in 5 priority sectors: transport, communication, tourism, financial and business services. Nevertheless, there has been little progress in negotiations and it is unlikely that these will be finalised by the end of 2020. Phase II negotiations of AfCFTA comprise intellectual property rights, competition and investment policy. Although set to be completed by June 2021, negotiations have not started yet[4]. Phase III negotiations on e-commerce are set to commence in 2021. The COVID-19 pandemic led to significant delays in the negotiating process, as well as a delay in the start of trade, under the AfCFTA regime, originally planned for July 2020. Despite technical difficulties, the 12th Meeting of AfCFTA Senior Trade Officials (STO), as well as the African Ministers of Trade (AMOT) meeting took place virtually at the end of September. The AU Extraordinary Summit is scheduled for December 5th, marking a deadline to finalise work on core issues of rules of origin, tariff offers and services offers.

The start of trade in goods is planned for January 2021. In the event that all outstanding rules of origin are not agreed by the time of the Extraordinary Summit, preferential trade commences on those products where there are agreed rules of origin and tariff offers. At the same time, implementing the agreement remains a daunting task. The newly founded AfCFTA Secretariat in Accra, Ghana, operating under the leadership of Wamkele Mene, will supervise implementation. Nevertheless, the decisive arena will shift from the continental to the national level, where several other steps need to be completed. These are the establishment of national committees to facilitate implementation as well as technical steps such as the alignment of domestic laws to the AfCFTA instruments, putting in place necessary documentation (e.g. customs declarations, certificates of origin, transit documents), adapting customs, standards and trade facilitation documents in national authorities, as well as comprehensively informing all relevant stakeholders.

Truly free intra-African trade can be expected from 2035 onwards (UNECA, 2018).

Such implementation work notwithstanding, will take at least 10 years to fully implement the agreement according to the liberalisation schedule it envisages. Therefore, truly free intra-African trade can be expected from 2035 onwards (UNECA, 2018).

The role of the European Union

The European Union has been supporting the AfCFTA since its launch in 2018 through its Pan-African Programme (PANAF), with EUR 72.5 million allocated for the time period 2014-2020. Of these, EUR 36.1 million were already attributed up until 2019. The amount is shared between support to AfCFTA negotiations, so far totalling around EUR 21 million, and support to implementation (EUR 16 million)[5]. In addition to facilitating negotiation fora or providing technical studies upon AU demand, the EU has also been supporting AfCFTA advocacy via financing the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA). The EU, via a cooperation with the International Trade Center (ITC) also contributed to establishing the African Trade Observatory, which aims to provide an evidence-based basis for conducting trade in Africa.

The European Union has been supporting the AfCFTA since its launch in 2018 through its Pan-African Programme (PANAF), with EUR 72.5 million allocated for the time period 2014-2020.

Implementation support has so far focused on supporting national customs administrations in AU Member States and Regional Economic Communities in the harmonisation of tariff nomenclature and adoption of the Harmonized System (HS), in partnership with the World Customs Organization (WCO). The EU is also supporting the development of national AfCFTA implementation strategies in pilot countries (with UNECA) as well as the development of national capacities in the field of intellectual property rights (with the EU Intellectual Property Office – EUIPO).[6]

Several EU Member States, most notably Germany, France, Sweden and Denmark, are also involved in supporting the AfCFTA via their own development cooperation agencies and initiatives. There are increased joint communication and coordination efforts, e.g. informal donor meetings and scoping discussions before new project phases, in order to avoid duplication of work.

The road ahead

The economic impacts of the AfCFTA are generally difficult to foresee, and distributional effects hard to estimate. Existing studies predict an increase of intra-African trade between 16% (IMF, 2019) and 84% (Abrego et al, 2019) as a result of tariff liberalisation, although most estimations hover around 14% (AfDB, 2019) to 25% in the year 2040 (UNECA, 2018). The large variance in the results is due to differences in the methodology applied and specifications of the models used[7]. A key takeaway is that tariff liberalisation by itself will not be enough: neither for trade, where non-tariff barriers, such as customs bottlenecks, poor trade logistics and infrastructure play a considerable role (IMF, 2019), nor for economic growth. Cutting tariffs can increase regional GDP by 0.7%-1%, but “the[ir] elimination is not crucial to boost growth in the region” (Chauvin et al, 2016, 16).

Despite the forecasted benefits of the AfCFTA, plenty of challenges remain. Production and transport of goods are currently impaired by a lack of infrastructure (electricity, roads, storage services, etc.) as well as a lack of access to capital and foreign currency and insufficient skilled human capital. The current pandemic furthermore showed the limitations of a fragmented African market. COVID-19 has hampered GDP growth rates in Africa, with economies dependent on commodities trade or tourism particularly hard hit (World Bank, 2020). Tariffs for medical inputs are high (UNECA, 2020), and transport of goods is often difficult.

Despite the forecasted benefits of the AfCFTA, plenty of challenges remain.

Liberalised trade in medical services, medical equipment such as masks or protective gear, or strong pharmaceutical value chains, capable of exporting within the continent, would be helpful steps in mitigating the impact of the pandemic. If accompanied by a developed infrastructure (cargo services, road and air transport infrastructure, storage services for medicine, a developed financial infrastructure enabling cashless payments), these measures could substantially improve the quality of delivery for medical systems, as well as contribute to mitigating economic impacts. The AU has recognised these needs and aims to create an e-commerce platform, as well as a Pan-African Payment Systems and Settlements (PAPSS) in time for the start of trade under the AfCFTA.

It therefore makes sense to reconsider the support strategy in light not only of EU interests and AfCFTA developments, but also recent economic incidents such as COVID-19.

Industrialisation has also re-emerged as a key area of focus for the AU. Studies find a historical tendency towards deindustrialisation in Sub-Saharan Africa (Jalilian & Weiss, 2000) and a constantly declining share of manufacturing and industry value added, a trend that has continued in recent years (Aryeetey & Moyo, 2011). Industrialisation is instrumental to fulfill the AfCFTA’s promise to boost trade in manufactures and job creation. It has also been flagged as a key strategy in the fight against the COVID-19 pandemic.[8]

The new phase of EU support starting in 2020 is coinciding with the proposed start of the trade under the AfCFTA. It therefore makes sense to reconsider the support strategy in light not only of EU interests and AfCFTA developments, but also recent economic incidents such as COVID-19. Continuing support in areas like Sanitary and Phytosanitary standards (SPS), rules of origin or the African Trade Observatory will remain relevant to facilitate the start of trade. The EU has furthermore acknowledged the importance of infrastructure and committed to further support the Programme for Infrastructure in Africa (PIDA)[9]. Aligning EU support with AfCFTA priorities, also in other programme areas not necessarily related to trade, such as the G20 Compact with Africa and the European External Investment Plan (ETTG, 2020) would be a welcome boost to AfCFTA implementation.

Phase II negotiations are currently attracting much attention from donors, with the EU displaying interest in topics such as competition policy or intellectual property rights[10]. Other EU partners such as ITC have also commenced project work on Phase II topics with funding from EU Member States. However, there is a risk of grabbing innovative topics for the sake of political signalling, although work on intellectual property rights and competition policy negotiations has not started yet. Donor-led activities in these areas risk channelling funds away from projects that are more relevant to the African Union and its Member States. In a status quo where less than half of the AfCFTA’s State Parties have concluded their tariff liberalisation offers, and AU Member States are tasked with containing COVID-19 while finalising negotiations and beginning AfCFTA implementation at the same time, there will be limited absorption capacity. Close coordination with the AU and Member States is needed to ensure sustainability of results.

The EU should coordinate its support with African actors as well, and where possible, complement their interventions.

Another dimension to consider is the political significance of the AfCFTA. The agreement is an unprecedented display of African unity, sending a clear political signal regarding Africa’s agenda of self-determination. It will likely improve the continent’s negotiating position with the EU, who has expressed the intention to move towards an -EU-AU free trade deal[11]. Since AfCFTA tariff offers are partly submitted at Regional Economic Communities (REC) level (see above for CEMAC, ECOWAS, SACU and EAC), we can also expect a possible strengthening of the role of RECs, within Africa but also vis-a-vis the EU. The strong pan-African aspect of the AfCFTA also includes cooperations with key non-state African actors, such as the AfroChampions, organisation[12], which aims to provide logistical and technological support, and the African Export-Import Bank (Afreximbank,) who launched an AfCFTA Adjustment Facility for Member States worth USD 1billion[13]. The EU should coordinate its support with African actors as well, and where possible, complement their interventions.

The agreement is an unprecedented display of African unity, sending a clear political signal regarding Africa’s agenda of self-determination.

Aligning existing EU-AU trade regimes with the AfCFTA is a topic that requires more exploration and a potential area of support from the EU. Historically, the EU has not always been perceived as conducive to African regional economic integration. The EU’s European Partnership Agreements (EPA) have been negotiated with country clusters but not always with RECs, due to competing interests within RECs and differing incentives between the “Everything but Arms (EBA)” and EPA regimes (Krapohl & Van Huut, 2019). The EU therefore needs to overcome historical mistrust, which is, at times, still present, and be aware that African integration may take on a different trajectory than the one the EU has historically followed. At the end of the day, the AfCFTA’s goal is not to replicate the EU model, but rather to provide an alternative path of African-led regional economic integration.

- Abrego, M. L., Amado, M. A., Gursoy, T., Nicholls, G. P., & Perez-Saiz, H. (2019). The African Continental Free Trade Agreement: Welfare Gains Estimates from a General Equilibrium Model. International Monetary Fund.

- African Development Bank, 2019. “Integration for Africa’s Economic Prosperity”. Chapter 3 in African Economic Outlook 2019. African Development Bank Group, Abidjan. Accessed 20.11.2020 at https://www.afdb.org/fileadmin/uploads/afdb/Documents/Publications/2019AEO/AEO_2019-EN-CHAP3.pdf

- Aryeetey, E., & Moyo, N. (2011). Industrialisation for Structural Transformation in Africa: Appropriate Roles for the State. Journal of African Economies, 21(suppl 2)

- Chauvin, D., N. Ramos and G. Porto, 2016. “Trade, Growth, and Welfare Impacts of the CFTA in Africa.” Accessed 20.11.2020 at https://hesso.tind.io/record/2006/files/Depetris-Chauvin_2017_trade_growth_welfare.pdf

- Douglas Zhihua Zeng (June 2020). How will COVID-19 impact Africa’s trade and market opportunities? World Bank. Accessed 20.11.2020 at https://blogs.worldbank.org/africacan/how-will-covid-19-impact-africas-trade-and-market-opportunities

- European Think Tanks Group (ETTG). Advancing EU-Africa cooperation in light of the African

- Continental Free Trade Area. September 2020. Accessed 20.11.2020 at https://acetforafrica.org/acet/wp-content/uploads/publications/2020/09/ETTG-EU-Africa-Cooperation.pdf

- International Monetary Fund (2019) “Is the African Continental Free Trade Area a Game Changer for the Continent?”. Chapter 3 in Regional economic outlook. Sub-Saharan Africa: recovery amid elevated uncertainty. International Monetary Fund, Washington D.C.

- Jalilian, H., & Weiss, J. (2000). De-industrialisation in sub-Saharan Africa: myth or crisis?. Journal of African Economies, 9(1), 24-43.

- Krapohl, S., & Van Huut, S. (2019). A missed opportunity for regionalism: the disparate behaviour of African countries in the EPA-negotiations with the EU. Journal of European Integration, 1-18.

- Tregenna, F. (2015). Deindustrialisation, structural change and sustainable economic growth. (UNUMERIT Working Papers; No. 032). Maastricht: UNU-MERIT.

- United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (2018). An empirical assessment of the African Continental Free Trade Area modalities on goods. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Accessed 20.11.2020 at https://www.uneca.org/sites/default/files/PublicationFiles/brief_assessment_of_afcfta_modalities_eng_nov18.pdf

- United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (2020) Trade Policies for Africa to Tackle Covid-19, African Trade Policy Centre. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Accessed 20.11.2020 at https://www.uneca.org/publications/trade-policies-africa-tackle-covid-19

[1] An overview of Agenda 2063’s framework and policy priorities can be found here: https://au.int/en/agenda2063/overview

[2] The status of AfCFTA ratification can be found here: https://www.tralac.org

[3] Regional Economic Communities (RECs) are groupings of African states with varying degrees of economic integration, ranging from simple preferential trade areas to monetary or customs unions, and frequently overlapping memberships. An overview of the RECs can be found here: https://au.int/en/organs/recs

[5] Source: EU-AU Partnership Factsheet, retrieved 20.11.2020 at: https://africa-eu-partnership.org/en/afcfta

[6] Source: EU-AU Partnership Factsheet, retrieved 20.11.2020at: https://africa-eu-partnership.org/en/afcfta

[7] Since there are various ways to model such simulations, results change depending on model specification and are often not comparable. The assumptions of these models also often do not match the reality of African countries, whose markets are often insufficiently developed and characterised by information asymmetries, a large informal sector and negative externalities. Data availability also plays a significant role: as data is frequently not available, most ex ante studies analysing the AfCFTA only investigate 16-27 countries. Results are thus to be taken with a grain of salt.

[8] Opening remarks of AUC Commissioner for Trade and Industry Albert Muchanga at the 3rd AU Symposium on Special Economic Zones and Green Industrialisation, 7 May 2020.

[9] 10th African Union Commission – European Commission Meeting – Joint Communique, 27 February 2020, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Retrieved 20.11.2020 at https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/statement_20_365

[11] Jean-Claude Juncker State of the Union address to European Parliament, 12 September 2018, Strasbourg, France.

[12] AfroChampions is a public-private partnership driven by key African business leaders under the umbrella of the AfroChampions organisation. More information on the initiative can be accessed here: https://au.int/fr/node/34022

[13] Further information on the Adjustment Facility and Afreximbank’s AfCFTA support can be accessed here: https://www.afreximbank.com/afreximbank-announces-1-billion-adjustment-facility-other-afcfta-support-measures-as-african-leaders-meet/

About the article

ISSN 2305-2635

The views expressed in this publication are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Austrian Society of European Politics or the organisation for which the author is working.

Keywords

AfCFTA, intra-African trade, international trade, regional economic integration

Citation

Lungu, I. (2020). The African Continental Free Trade Area: The Role of EU Support for Africa’s Historic Trade Agreement. Vienna. ÖGfE Policy Brief, 25’2020