Policy Recommendations

- The fight against corruption in Bulgaria should result in a solid track-record of final convictions in high-level corruption cases, meeting the expectations of active citizenship and increasing trust in institutions, which is critically low at present.

- National legislation, court case-law and political practice should envisage mechanisms for responding to international reports of large-scale corruption such as those under the Magnitsky Act.

- Raising the awareness of citizens and the business community about the effects of (the lack of) reforms in the judiciary.

Abstract

The Policy Brief argues that Bulgaria is experiencing a negative transformation, a transition from post-communism to post-democracy expressed in the transition from corruption to endemic corruption and state capture. The Policy Brief is structured in three parts. The first part introduces the theoretical model of the post-communist post-democracy (Krasteva 2019) based on the concept of “symbolic-ideological hegemony” (Schmitter 1994). It articulates three different transformations in Bulgaria’s post-communist development, each one of them defining in a different way the rule of law and justice as well as the Europeanisation of the country and region as a political project. The second part examines civic mobilisations for rule of law and justice as an expression of and catalyst for the formation of active and contestatory citizenship. The third part analyses the three-pole model of state capture. The article examines also the alliance for change and rule of law.

****************************

State Capture versus Contestatory Citizenship in Bulgaria

Introduction

By a symptomatic coincidence of the academic and political calendars, I am writing this Policy Brief amidst a major corruption scandal sparked by the largest single action to date targeting corruption in a particular country under the Magnitsky Act.[1] The objective of this Policy Brief is twofold: on the one hand, to analyse the current heated political debate on rule of law and justice in Bulgaria, and on the other, to conceptualise, in an innovative and original way, the political transformations that make giant corruption scandals – such as the present scandal, many past and, most probably, future ones, too – foreseeable and inevitable. The Policy Brief is structured in three parts. The first part introduces the concept of the transition from post-communism to post-democracy (Krasteva 2019; Krasteva and Todorov 2020), which articulates three different transformations in Bulgaria’s post-communist development, each one of them defining in a different way the rule of law and justice as well as the Europeanisation of the country and the region as a political project. The second part examines civic mobilisations for rule of law and justice as an expression of and catalyst for the formation of active and contestatory citizenship. The third part analyses the corruption model of state capture.

From post-communism to post-democracy: an unfinished battle between democracy and state capture

This part seeks an answer to the question of why rule of law is more problematic in Bulgaria today than at the earlier stages of the country’s democratisation. The answer is sought in the perspective of the post-communist transformation of the transformation (Mickenberg 2015; Krasteva 2019). The theoretical model of the post-communist post-democracy (Krasteva 2019; Krasteva and Todorov 2020) is based on the concept of “symbolic-ideological hegemony” (Schmitter 1994) as a key criterion for distinguishing the transformations: the transformation of a particular transformation project into a hegemonic project that dominates political discourses, strategies and policies, on the one hand, and values and attitudes on the other.

The first democratic transformation started as “the end of history” (Fukuyama 1992), as the end of rivals of liberal democracy and the rise of the latter as the grand narrative of the post-communist transformation. Rule of law and justice were key elements of this grand narrative together with the geopolitical reorientation of Bulgaria through Euro-Atlantic and European integration. The democratic transformation in Bulgaria was designed as a strategic and long-term horizon. The country’s political development, similar to the one in Central and Eastern Europe (Levitsky and Way 2010; Zankina 2016) however, significantly modified the linear teleological vision and only a decade and a half after the beginning of the transition set out to “transform the transformation” (Mickenberg 2015).

The national-populist transformation in Bulgaria has still not crystallised into an illiberal democratic project.

The national-populist transformation is the second after the beginning of the post-communist transition and the first that has reversed the direction of the democratic transformation. National populism erodes democracy by both creating democratic and institutional deficits (Zankina 2016) and by eroding the foundation of democracy. Whereas the democratic transformation began from the centre – not in the partisan but in the political sense, as a critical majority of politicians and citizens in favour of consolidating Bulgaria’s democratisation – the second began from the national-populist far right (Krasteva 2016a). The national-populist transformation in Bulgaria has still not crystallised into an illiberal democratic project. Two negative changes of the transformation are key to the present analysis. The first is the shift of priority from rule of law and justice to identity politics. It is no accident that the key party actors of identity politics, the VMRO (Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organisation) and the DPS (Movement for Rights and Freedoms), are among the most corrupt parties in Bulgaria. The VMRO, which is using Bulgarian national identity for political purposes, ‘sells’ one of its most respected forms – Bulgarian citizenship. The State Agency for Bulgarians Abroad, which is headed by VMRO representatives, has been at the centre of many scandals and investigations about corruption in granting Bulgarian citizenship. The DPS is an example of an oligarchic and clientelistic party. Representatives of both parties are among the targets of the sanctions under the Magnitsky Act. The second change is the mainstreaming of far-right populism which has gradually encompassed key political actors like the BSP (Bulgarian Socialist Party), President Rumen Radev, and the fluid GERB (Citizens for European Development of Bulgaria). Identity politics has begun to shape not only Bulgaria’s domestic policy but also its foreign policy. Most indicative in this respect is GERB’s radical reorientation. During the Bulgarian Presidency of the Council of the European Union (EU) in the first half of 2018, Bulgaria’s strategic priority was Europeanisation of the Western Balkans. After it ended, the ruling coalition of GERB and the United Patriots blocked North Macedonia’s EU accession.

A popular saying summarises this specificity: other states have the mafia; in Bulgaria, the mafia has the state.

Post-democracy is the latest wave of post-communist transformations. Post-democracy is understood in the vein of Colin Crouch (2004) as a regime in which there are democratic institutions but they are empty shells – stripped of the function to serve the public interest, they have been subordinated to private interests. At the centre of this transformation is state capture. State capture conceptually synthesises the transition from corruption as a deviation from the system to a fundamental transformation of the political system itself which is increasingly dominated by “policy for cash” (Power and Taylor 2011: 7). Whereas in some countries in Eastern Europe “private actors buy influence over legislation and regulation in order to produce favorable laws for their businesses” (Hulsey 2018: 16), in countries like Bulgaria and Hungary political parties are at the centre of state capture “as core initiating actors who are at least as interested in political control as illicit economic gain” (Hulsey 2018: 16–17). A popular saying summarises this specificity: other states have the mafia; in Bulgaria, the mafia has the state. The post-democratic transformation is invisible: it is not a publicly declared project of the elites, let alone of citizens. It does not propose a new political project but deprives democracy of attractiveness, content, a horizon, a “metaphysic of hope” (Ganev 2007: 197), transforming politics and governments into a “web of political relations” (Tilly 1975: 25).

The degradation of the rule of law is one of the most conspicuous manifestations of the post-democratic transformation: “the rule of law in Bulgaria during the last decade has been backsliding. The Rule of Law Index (2017-18) gives evidence that Bulgaria, together with Hungary, have the lowest and declining overall rule of law scores among the EU member states (Todorova 2020: 235). Velina Todorova (2020) demonstrates that the impartiality and the independence of the judicial system are in constant decline, identifies the political capture of the judiciary, and concludes that “all three powers use the law in such a way as to generate channels of corruption, which undermine the law’s fundament” (Todorova 2020: 251).

The deterioration of the democratic transformation into a nationalist-populist and a post-democratic one explains the dethroning of the rule of law and justice from their priority position of key pillars of the democratic project. The next part will examine the antidote to this trend – namely, the formation of a contestatory civic ethos.

Anti-corruption civic mobilisations and the formation of contestatory citizenship

If the key actors of the first democratic revolution were the elites, in the second it was the citizens who took the democratic project into their own hands, striving to refound democracy.

On 14 June 2013, controversial media mogul Delyan Peevski was elected by Parliament as head of the State Agency for National Security. This triggered the largest and longest protests in contemporary Bulgarian history, which lasted about 400 days. They were against state capture – against the behind-the-scene networks, shady backroom politics, the oligarchic interests pulling the strings of the political game. These protests did not achieve their goals – neither the resignation of the coalition government of the Bulgarian Socialist Party and The Movement for Rights and Freedoms nor the dismantling of the model of shady backroom politics. But they achieved another two significant results that are key to this Policy Brief. The first is the formation of contestatory citizenship through mass protests. The protests become social movements when they leave the virtual world and flood the public square, when the “space of flows” merges with the “space of places”, when virtual networks are extended to the occupied buildings and blocked streets (Castells 2012). The protests that started in June 2013 were a watershed: if until then young people were passive or mobilised in relatively small-scale green actions or online, the year of protest catalysed contestatory citizenship formed around four axes: – “augmented citizen”, “indignation”, “voice”, and “networked individual”. The second change was so significant that it has been defined as a “second democratic revolution” (Krasteva 2016b). If the key actors of the first democratic revolution were the elites, in the second it was the citizens who took the democratic project into their own hands, striving to refound democracy.

Civic mobilisations are the immune system of democracy.

Protesting citizens are the antidote to state capture and post-democracy. Civic mobilisations are the immune system of democracy. This is precisely what we can argue for Bulgaria too. In the summer of 2020, Bulgarian citizens once again took to the streets, aspiring to reconquer the state captured by the post-democratic elites (Krasteva 2020). The main demands were the resignations of Prime Minister and GERB leader Boyko Borisov, carrier and upholder of endemic corruption, and Prosecutor General Ivan Geshev, who has turned the prosecution service into a weapon against the government’s political opponents and a shield for the GERB-affiliated oligarchs. Two characteristics of the 2020 protests are important for this analysis – their faces were young, they were educated and active people; rule of law and reform of justice were the key slogans:

- No accountability without justice and rule of law. The protests went beyond the mere resignation of the Prosecutor General and demanded a fundamental reform – the convocation of a Grand National Assembly to amend the Constitution regarding the judiciary. The reform of the judiciary should even precede the political transformation. As a protestor[2] pointed out: “It doesn’t matter who rules if there is no independent prosecutor’s office to work for the rights of the people, not the oligarchs and the mafia” (Krasteva 2020).

- Transformation, not only resignation. “Systemic change, not replacement”, demanded another protestor. A student in philosophy summarised the ‘total’ protest for radical transformation: “against the violation of law, against the authoritarian, pseudo-democratic power linked to the mafia, against the politicisation of all spheres of life, against the status quo and against conformity with the status quo, which cries ‘everyone is a bad guy, what to do?’” (Krasteva 2020).

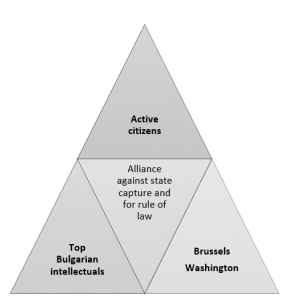

Alliance against state capture and for rule of law

Source: Author’s elaboration

The summer 2020 protests outlined the alliance for change, against state capture, and for rule of law. At its top are active citizens. They appear in two roles – contestatory and supporting. Protesters brought a future into the political temporality blocked by anti-reformist post-democratic elites in three fundamental ways:

- Formation of a new generation of contestatory citizens: “These protests are the beginning of a new generation of Bulgarian citizens, more responsible, more vigilant, more critical” (Kamen, 21); “We are the alternative – voting, protesting, fighting in all democratic ways” (Dafina, 22, law student);

- Building a political culture of activism for making the elites accountable: “Civic engagement and social activity, no matter who is in power! Today’s protests should not be the end of a struggle, but the beginning of a more awake society” (Ani);

- Defining the political temporality not as a continuation of the post-democratic status quo, but as a future and change: “I want a future in Bulgaria” (Ani); “It’s time for change!” (Bojidar) (Krasteva 2020).

The majority of Bulgarian citizens supported the protests and shared their critical position. This support had two faces as well – ad hoc support for the protests’ demands and agreement as to their main cause – approximately 80% of Bulgarian citizens thought that there is widespread corruption in Bulgaria (Eurobarometer 502, 2019).

The second pillar of the alliance for change is the elite of Bulgarian culture – 123 intellectuals, internationally acclaimed artists such as Theodore Ushev and writer Georgi Gospodinov, who signed an Open Letter in support of the protests.

The contestatory ethos (Krasteva, Saarinen and Siim 2019: 275) and active citizenship with two types of agency – protesting youths, and the intellectual and cultural elite – are an outstanding expression of the broad public support for the demands for accountability of elites, reform of the judiciary, and restoration of the rule of law in Bulgaria.

The third pillar of the alliance for change are Brussels and Washington. During the protests, a report by two US senators on endemic corruption in Bulgaria was released, and so was the European Commission’s successive critical report on the rule of law situation in the country: ‘Lack of results in the fight against corruption is one of the key aspects raised throughout the summer 2020 protests. A solid track-record of final convictions in high-level corruption cases remains to be established” (EC 2020). It is not the Bulgarian authorities, it is the Bulgarian citizens in the public square who speak in the language of EU institutions and the US administration.

The Magnitsky Act – paradoxically, disclosures of abuses known to all come like a bolt from the blue

The Magnitsky disclosures came like a bolt from the blue to Bulgaria’s political landscape. Two groups of reasons explain this shattering impact.

The first are external reasons and find expression in the sanctions imposed against six Bulgarian individuals and more than 60 entities in Bulgaria. They are sanctioned under two different laws[3] which provide for a variety of restrictions ranging from ineligibility for entry into the US to cutting off access to the US financial system. These sanctions are unprecedented in Europe – before them, Magnitsky sanctions had been imposed on only one oligarch from Slovakia with six companies, and one in Latvia with four companies. These sanctions are unprecedented in scope and weight in the entire history of the Magnitsky Act. They are an expression of President Biden’s doctrine that corruption is an international problem, a risk and threat to international security. They are also unique in that, unlike the European Commission’s criticisms, they have named the oligarchs and senior public officials involved in corruption.

The second group of reasons are domestic. The impact of the sanctions has been intensified as it coincides with the caretaker cabinet’s efforts to conduct a sweeping audit of GERB’s rule and bring to light large-scale corruption schemes and practices in numerous spheres.

The disclosures under the Magnitsky Act clearly outlined the three-dimensional structure of corruption in Bulgaria.

The paradox of the disclosures made under the Magnitsky Act is not in that they said hitherto unknown things and names; it is in that they said, with the power of the American voice, things which theory had conceptualised and analysed, and names which the protesters had shouted in the public square. The disclosures under the Magnitsky Act clearly outlined the three-dimensional structure of corruption in Bulgaria.

The three-dimensional structure of the corruption model in Bulgaria

Source: Author’s elaboration

At the top of the pyramid is GERB which, having been in power for a decade, bears the brunt for the rise of endemic corruption – the term sums up the US diagnosis. Its other pole is Delyan Peevski with the support of the DPS. He is ample proof of the political bias of the prosecution service which never pressed charges against him in all those years when it was crystal clear to Bulgarian public opinion, the European Commission, and the US administration which side of the law he was on. The same political bias of the prosecution service can be seen in the third pillar – Vasil Bozhkov, a gambling tycoon nicknamed The Skull, who is under 19 charges, which, however, were pressed against him only after he was disowned by the ruling GERB party. Bozhkov is one of the channels of Russian influence and hybrid risks in Bulgaria.

The final remarks can be summarised in four groups.

The transition from post-communism to national-populism to post-democracy is an expression of negative transformations, of transition from corruption to endemic corruption and state capture.

The agency of the post-democratic transformation is the politico-oligarchic elite. It does not have a definite political colour, but the primary responsibility rests with GERB, which was in power for a whole decade, the VMRO, GERB’s coalition partner, and the DPS, its unofficial partner. The prosecution service is more often part of the problem than of the solution – it has kept its eyes wide shut when it comes to the oligarch Delyan Peevski, and pressed charges against the oligarch Vasil Bozhkov only after the end of his close relationship with GERB.

The electoral expression of the civic mobilisations is the restructuring of the party scene.

The electoral expression of the civic mobilisations is the restructuring of the party scene. Three parliamentary elections in just one year (2021) were needed for the fundamental transformation of the party system – three new parties and coalitions, named ‘parties of the protest’ or ‘parties of the change’, entered the Parliament: ‘We Continue the Change’ ‘There Is Such a People’, ‘Democratic Bulgaria’.

‘Citizenship remains a significant site through which to develop a critique of pessimism about political possibilities’ (Isin and Nyers 2014: 9). The last few years have seen the formation and consolidation of an active civic ethos and contestatory citizenship which demand accountability of elites, reform of the judiciary, and rule of law in Bulgaria. Did they find an adequate political representation in the parties of the protest and will the latter would engage in reforming Bulgaria from post-democratic state capture to revitalised democracy – is the major challenge for the months and years to come…

*******************************

Photographer: Etienne Ansotte

© European Union, 2017

Source: EC – Audiovisual Service

*******************************

The Policy Brief is published in the framework of the WB2EU project. The project aims at the establishment of a network of renowned think-tanks, do-tanks, universities, higher education institutes and policy centres from the Western Balkans, neighbouring countries and EU member states that will be most decisive for the enlargement process and Europeanisation of the region in the upcoming years. The WB2EU project is co-funded by the European Commission under its Erasmus+ Jean Monnet programme. The European Commission support for the production of this publication does not constitute an endorsement of the contents which reflects the views only of the authors, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein.

[1] On 2 June the United States (US) announced it was sanctioning six Bulgarian individuals and more than 60 entities associated with them over their involvement in significant corruption. The Global Magnitsky Human Rights Accountability Act (2016) allows the U.S. government to sanction foreign government officials implicated in human rights abuses and corruption anywhere in the world. ‘The man behind the global Magnitsky push, US financier Bill Browder, says the beauty of the penalties is that they target individual wrongdoers rather than putting whole nations under punishing economic sanctions’ (Croch and Galloway 2020).

[2] All quotes are from the “Voices of protest” platform of the Policy and Citizens’ Observatory, analysed on OpenDemocracy (Krasteva 2020).

[3] ZThe Global Magnitsky Human Rights Accountability Act and Section 7031(c) of the Department of State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs Appropriations Act.

Castells, M. (2012) Networks of Outrage and Hope: Social Movements in the Internet Age. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Crouch, C. (2004) Post-Democracy. Cambridge: Polity Press.

EC (2020) 2020 Rule of Law Report. Country Chapter on the rule of law situation in Bulgaria. 30 September. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?qid=1602582109481&uri=CELEX%3A52020SC0301

Eurobarometer 502 (December 2019) Bulgaria – corruption. https://www.infobusiness.bcci.bg/content/file/ebs_502_fact_bg_bg_(1).pdf

Fukuyama, F. (1992) The End of History and the Last Man. New York: The Free Press.

Ganev, V. I. (2007) Preying on the State: The Transformation of Bulgaria after 1989. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Grouch, S. and A. Galloway (2020) What are the Magnitsky sanctions and why does Russia oppose them? In: The Sydney Morning Herald, 7.12.20. https://www.smh.com.au/national/what-are-magnitsky-sanctions-and-why-does-russia-oppose-them-20200909-p55tqm.html

Hulsey, J. (2018) Institutions and the Reversal of State Capture: Bosnia and Herzegovina in Comparative Perspective. Southeastern Europe 42 (1): 15–32.

Isin E. and Nielsen G. eds (2014).’Introduction: globalizing citizenship studies’ in Routledge Handbook of Global Citizenship Studies, edited by Engin Isin and Peter Nyers. London&New York: Routledge, 2014, 1-11

Krasteva A. (2020) Voice, not exit. Portraits of protesters. OpenDemocracy, 17 August. https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/can-europe-make-it/voice-not-exit-portraits-protesters/

Krasteva, A. (2019) Post-democracy: there’s plenty familiar about what is happening in Bulgaria. OpenDemocracy, 20 November. https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/can-europe-make-it/bulgaria-post-communism-post-democracy/

Krasteva, A. (2016a) The Post-Communist Rise of National Populism: Bulgarian Paradoxes. In: G. Lazaridis, G. Campani and A. Benveniste (eds.), The Rise of the Far Right in Europe: Populist Shifts and ‘Othering’. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 161–200.

Krasteva A. (2016b) Occupy Bulgaria: Or, the Emergence of the Post-Communist Contestatory Citizenship. Southeastern Europe 40 (2): 158–187.

Krasteva, A., A. Saarinen and B. Siim (2019) Citizens’ Activism for Reimagining and Reinventing Citizenship Countering Far-Right Populism. In: B. Siim, A. Krasteva and A. Saarinen (eds.), Citizens’ Activism and Solidarity Movements: Contending with Populism. Palgrave Studies in European Political Sociology. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 265–292.

Krasteva A. and Todorov A. (2020) From Post-Communism to Post-Democracy: The Visible and Invisible Transformations. Southeastern Europe 44 (2): 177–207.

Levitsky A. and L. A. Way (2010) Competitive Authoritarianism: Hybrid Regimes After the Cold War. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Minkenberg, M. (ed.) (2015) Transforming the Transformation? The East European Radical Right in the Political Process. New York: Routledge.

Power, T. J. and M. M. Taylor. (2011) Introduction: Accountability Institutions and Political Corruption in Brazil. In: T. J. Power and M. M. Taylor (eds.), Corruption and Democracy in Brazil: The Struggle for Accountability. Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, pp. 1–28.

Schmitter, P. C. (1994) Dangers and Dilemmas of Democracy. Journal of Democracy 5 (2): 57–74.

Tilly, C. (1975) Reflections on the History of European State-Making. In: C. Tilly (ed.), The Formation of National States in Western Europe. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, pp. 3–83.

Todorova V. (2020) The Rule of Law in Bulgaria: State of Play and Trends (after 2010). Southeastern Europe 44 (2): 233–259.

Zankina, E. (2016) Theorizing the New Populism in Eastern Europe: A Look at Bulgaria. Czech Journal of Political Science 2: 182–199.

About the article

ISSN 2305-2635

The views expressed in this publication are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Austrian Society of European Politics or the organisation for which the author is working.

Keywords

Bulgaria, rule of law, justice, post-democracy, state capture, citizenship

Citation

Krasteva, A. (2021). State Capture versus Contestatory Citizenship in Bulgaria. Vienna. ÖGfE Policy Brief, 22’2021