Policy Recommendations

- Adjust the public debt reduction criterion: reinstating the “old” debt rule would imply an overly large upfront reduction in debt ratios entailing high social and economic costs. Reflecting the new realities of higher debt levels, combined with very low or even negative interest rates, a strong case can be made for raising the target value for public debt ratios and /or reducing the required pace of debt reduction.

- Move towards simpler fiscal rules based on observable indicators for measuring compliance, perhaps in the form of a medium-term expenditure rule. However, refrain from introducing some sort of a “green golden rule” by exempting certain categories of public expenditure as this would probably raise endless discussions given the fuzzy distinction between investment expenditures and other growth-enhancing expenditures.

- Consider incentivising the double transition towards green and digital by remodelling the Recovery and Resilience Facility once it expires as a permanent fiscal capacity to support and stabilise broad categories of public investment in EU member states.

Abstract

In marked contrast to the muddled European Union (EU) reaction to the financial crisis and its aftermath, the EU response to the COVID-19 pandemic has been impressively swift and comprehensive. Creating the Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF) and establishing a coherent framework for its implementation has involved constructive and intense policy dialogues between the European Commission and EU member states, leading to improved mutual understanding of challenges, while building trust and ownership. This bodes well for the debate about the reform of the EU`s fiscal rules. Four new characteristics of the current economic environment call for a reconsideration of the Maastricht rules: significantly higher values of public debt ratios, very low or even negative interest rates, limited effectiveness of monetary policy in the vicinity of the effective lower bound, and common debt issuance with the adoption of the RRF. Against this background, the reform needs to address the key challenges of simultaneously reducing high public debt and ensuring major investments in green transition and digital transformation, while simplifying the fiscal rulebook.

****************************

Returning to a “new normal”: revising the EU fiscal rulebook

1. Boosting recovery and resilience: NextGenerationEU and the Recovery and Resilience Facility

In marked contrast to the muddled European Union (EU) reaction to the financial crisis and its aftermath, the EU response to the COVID-19 pandemic has been impressively quick and comprehensive. The swift activation at the EU level of the ‘general escape clause’ of the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP) in March 2020 allowed EU member states to undertake measures to deal adequately with the crisis, while departing from the budgetary requirements that would normally apply under the European fiscal framework[1]. Additionally, backed by the EU SURE[2] instrument, member states provided strong support to business and workers, notably through large scale short time working schemes and substantial liquidity support to firms. Together with the working of normal automatic stabilisers in times of recession led to a strong increase in headline deficit and debt ratios, with the EU aggregate general government deficit rising from a historically low of around 0.5% of gross domestic product (GDP) in 2019 to around 7% in 2020.[3]

The European Central Bank (ECB) complemented the fiscal response with a broad set of monetary policy measures, in particular the establishment of the Pandemic Emergency Purchasing Programme (PEPP) initiated in March 2020. The PEPP is a temporary asset purchase programme of private and public sector securities, with net purchases running until March 2022. The ECB´s Governing Council decided to increase the initial €750 billion envelope for the PEPP by €600 billion on 4 June 2020 and by €500 billion on 10 December, for a new total of €1,850 billion.

In the third quarter of 2021, output and unemployment in the EU were virtually back to their pre-crisis levels, although the pace of recovery is uneven across countries.

Thus, the strategic interaction between fiscal and monetary policy to counter the economic fallout from the pandemic played out much smoother than in the wake of the financial crisis 12 years ago. Indeed, this joint and coordinated policy response was successful: the economic impact of the crisis on workers and firms has been far less severe than originally anticipated. In the third quarter of 2021, output and unemployment in the EU were virtually back to their pre-crisis levels, although the pace of recovery is uneven across countries.

The EU’s long-term budget, coupled with NextGenerationEU (NGEU), the temporary instrument designed to boost the recovery, will be the largest stimulus package ever financed in Europe. A total of more than €2 trillion in current prices (€2018 billion, to be precise) will help rebuild a post-COVID-19 Europe. It will be a greener, more digital and more resilient Europe. Looking forward, the newly created EU Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF) will promote an investment-rich recovery and growth-enhancing reforms by providing €338 billion in non-repayable support and up to €386 billion in loans (in current prices) throughout the period to 2026.

The EU’s long-term budget, coupled with NextGenerationEU (NGEU), the temporary instrument designed to boost the recovery, will be the largest stimulus package ever financed in Europe.

Creating the RRF and establishing a coherent framework for its implementation has involved constructive and intense policy dialogues between the European Commission and EU member states, leading to improved mutual understanding of challenges, while building trust and ownership. However, it should be acknowledged that this impressive cooperative effort has only been possible due to the absence of the deeply rooted moral hazard considerations that overshadowed the EU response to the financial crisis. In a sense, the pandemic unfolded behind Rawls´s veil of ignorance and, thus could not be framed as anyone´s fault. But obviously, insights gained from the functioning of the RRF framework – put bluntly, making it a success – will be extremely relevant for the broader economic governance of the Union. In particular, the implementation experience with the RRF will be highly pertinent for the debate on reforming the EU fiscal rulebook.

2. Returning to a new normal: revising the EU fiscal rulebook

The Maastricht fiscal architecture relies on limits for debt and the general government deficit. The reference values used are 3% for the deficit and 60% for the debt, both in terms of GDP. These reference values are not specified in the body of the Treaty. Instead, they are defined in an annexed protocol. These “reference values” are considered as pertinent in monitoring developments of public finances by the European Commission, with a view to identifying “gross errors” in the conduct of fiscal policy. However, these two reference values have no solid ground in either theory or empirical evidence. No such a claim was made at the time (or ever). If anything, one could point out that with a deficit of 3% and nominal GDP growth of 5% (not unrealistic some 30 years ago) public debt would stabilise at 60% (approximately the average value of debt of the Maastricht-12 in 1992).

The rulebook has grown increasingly complex with a multitude of indicators – often based on unobservable variables – hard to understand even for the informed insider.

Since the Maastricht Treaty and the adoption of the secondary legislation in 1997, the European fiscal rules have been constantly revised (without Treaty changes), notably through changes in the secondary legislation in 2005, 2008 and 2011, as well as various interpretative changes, such as those announced in the “Communication on the review of the flexibility under the Stability and Growth Pact” in 2015[4]. The rulebook has grown increasingly complex with a multitude of indicators – often based on unobservable variables – hard to understand even for the informed insider. In particular, the debt criterion has gained more prominence by introducing an explicit reference value for the pace of debt reduction towards the target value. But overall, the underlying framework has remained the same, and the 3% and 60% criteria are still the most salient feature of the SGP.

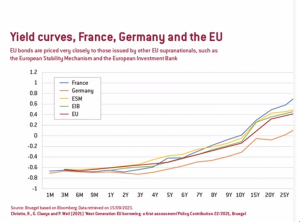

However, we no longer live in a Maastricht world and already in February 2020 the European Commission started fresh discussions on the contours of a revised EU fiscal framework. The debate had been on hold since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, but in autumn 2021 the reform discussion was relaunched, including a broad-based public consultation. The post-COVID-19 macroeconomic environment is marked by four new characteristics calling for a reconsideration of the Maastricht rules: significantly higher current values of public debts, very low or even negative interest rates, limited effectiveness of monetary policy in the vicinity of the effective lower bound, and common debt issuance with the adoption of the European recovery plan in 2020. In fact, the EU has swiftly moved to establish a full benchmark yield curve with maturities ranging from three months to thirty years.

However, we no longer live in a Maastricht world and already in February 2020 the European Commission started fresh discussions on the contours of a revised EU fiscal framework.

The French EU presidency and the newly formed German coalition government could now provide additional momentum to the debate. Basically, the reform needs to address the key challenges of simultaneously reducing high public debt and ensuring major investments in green transition and digital transformation, while simplifying the fiscal rulebook.

The French EU presidency and the newly formed German coalition government could now provide additional momentum to the debate.

Reducing high and divergent public debt ratios in a sustainable, growth-friendly manner[5] will be a key requirement of returning to new normal. In 2020, the aggregate debt-to-GDP ratio of the EU rose by over 13 percentage points, reaching around 92% (100% in the euro area). More than half of the EU member states recorded a debt above 60% of GDP, with Greece standing out with a debt above 200%. At the end of 2023, the debt ratio is expected to remain above 100% of GDP in six EU member states (Belgium, Greece, Spain, France, Italy, and Portugal), up from three member states at the end of 2019.

When economic conditions allow, resuming a path of reducing public debt-to-GDP ratios will be essential for maintaining sound public finances and avoiding persistent fiscal divergences between EU member states. At the same time, an overly large upfront reduction in debt ratios would entail high social and economic costs and be counterproductive. In particular, the request for annual debt reduction of 1/20th of the gap between the current debt level and a target of 60% cannot reasonably be upheld. A simple reinstatement of the SGP in 2023 would imply excessive and economically completely unwarranted fiscal retrenchment in highly indebted countries. Thus, either the required pace of debt reduction is considerably slowed down or, alternatively, the target level of public debt is adjusted to better reflect current circumstances, say to 100%. Obviously, a combination of the two is also possible, perhaps even with some country-specific variation.

Rather, a permanent EU facility to promote the green transition and digital transformation could be established when the RRF expires.

A growth-friendly composition of public finances should promote investment and support sustained, sustainable and inclusive growth. Reflection is needed on the appropriate role of the economic governance framework to incentivise national investment and reforms. Promoting green, digital, and resilience-enhancing public investment deserves special attention, given the long-term challenges facing our economy. However, introducing some sort of a “green golden rule” by exempting certain categories of public expenditure would probably raise endless discussions given the fuzzy distinction between investment expenditures and other growth-enhancing expenditures. Rather, a permanent EU facility to promote the green transition and digital transformation could be established when the RRF expires.

A simpler framework would contribute to increased ownership, better communication, and lower political costs for enforcement and compliance.

Achieving the overarching goals of simplification, stronger national ownership and better enforcement remains highly relevant. This calls for simpler fiscal rules using observable and more stable indicators for measuring compliance, perhaps in the form of a medium-term expenditure rule. Such a rule could require the government expenditure to grow in line with medium-term potential growth, which, while still unobservable, would be subject to less frequent revisions compared to annual estimates of the output gap. It also includes considering whether a clear focus on ‘gross policy errors’, as set out in the Treaty, could contribute to a more effective implementation. A simpler framework would contribute to increased ownership, better communication, and lower political costs for enforcement and compliance.

At this point in time, it is difficult to map out a “landing zone” of the discussion.

The future of the EU`s fiscal rulebook will not be an easy debate. Learning from the two crises of the more recent past and avoiding a renewed framing in terms of moral hazard could support a cooperative outcome. Future stability is in everyone’s interest and, moreover, positive country spill overs resulting from green investments will benefit all EU member states. However, some positioning along the old battlelines between the “frugals” and the “others” has already taken place. At this point in time, it is difficult to map out a “landing zone” of the discussion. But before going to battle, it may be useful for the parties to recall the central provisions of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) of Article 126 (“Member States shall avoid excessive government deficits”) and Article 121 (“Member States shall regard their economic policies as a matter of common concern and shall coordinate them within the Council”). While sticking to the spirit of the treaty, seeking a cooperative positive-sum solution is warranted, rather than again slipping away into dead-end discussions between the two extreme poles of “no debt union” and “de facto abolishing the SGP”.

3. Summary and policy recommendations

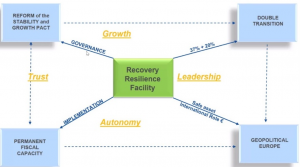

The creation of the RRF testifies to an improved mutual understanding of economic challenges in the EU, including between EU member states and the European Commission. The nature of the COVID-19 crisis as an exogenous shock to all has helped to come to a cooperative agreement and to avoid the nasty moral hazard considerations of the past. A successful deployment of the RRF will have an impact well beyond its basic twin objectives of stimulating reforms and investments, informing the debate about the reform of the SGP, supporting the green and digital transition, possibly serving as a blueprint for the hotly contested instrument of a permanent fiscal capacity, and hopefully strengthening the international economic weight of the EU by establishing a common safe asset.

Building on a successful deployment of the RRF

Source: Buti (2021)

The post-COVID-19 macroeconomic environment is characterised by four new characteristics calling for a reconsideration of the Maastricht rules: significantly higher current values of public debts, very low or even negative interest rates, limited effectiveness of monetary policy in the vicinity of the effective lower bound, and common debt issuance with the adoption of the European recovery plan in 2020. Against this background, the reform needs to address the key challenges of simultaneously reducing high public debt and ensuring major investments in green transition and digital transformation, while simplifying the fiscal rulebook. More specifically,

- adjust the public debt reduction criterion: reinstating the “old” debt rule would imply an overly large upfront reduction in debt ratios entailing high social and economic costs. Reflecting the new realities of higher debt levels, combined with very low or even negative interest rates, a strong case can be made for raising the target value for public debt ratios and/or reducing the required pace of debt reduction.

- move towards simpler fiscal rules based on observable indicators for measuring compliance, perhaps in the form of a medium-term expenditure rule. However, refrain from introducing some sort of a “green golden rule” by exempting certain categories of public expenditure as this would probably raise endless discussions given the fuzzy distinction between investment expenditures and other growth-enhancing expenditures.

- consider incentivising the double transition towards green and digital by remodelling the RFF once it expires as a permanent fiscal capacity to support and stabilise broad categories of public investment in EU member states.

Photo: The banner “Recovery Plan for Europe” on the front of the Berlaymont building: Next Generation

Photographer: Aurore Martignoni

Architect: André Polak, Berlaymont 2000, Lucien De Vestel, Jean Polak

© European Union, 2020

Source: EC – Audiovisual Service

Baldwin, R and B Weder di Mauro (2020), Economics in the time of COVID-19, CEPR Press.

Blanchard O J, Á Leandro and J Zettelmeyer (2021): “Redesigning EU Fiscal Rules: From Rules to Standards”, PIIE Working Paper No. 21/1.

Buti, M (2020), “Economic Policy in the Rough: A European Journey”, CEPR Policy Insight No. 98.

Buti, M and G Papacostantinou (2021), “Reshaping economic policy in the EU in the post-Covid world”, CEPR Policy Insight No. 109.

Buti, M and V Gaspar (2021), “Maastricht values”, VoxEU.org 8 July.

Christie, R., G. Claeys and P. Weil (2021) ‘Next Generation EU borrowing: a first assessment’. Policy Contribution 22/2021, Bruegel.

European Commission (2021), “Communication on one year since the outbreak of COVID-19: fiscal policy response”.

European Commission (2021), “Communication on the EU economy after COVID-19: implications for economic governance”.

Martin, P, J Pisani-Ferri, X Ragot (2021), “A new template for the European fiscal framework” VoxEU.org 26 May.

SURE (2020), The European instrument for temporary Support to mitigate Unemployment Risks in an Emergency. https://ec.europa.eu/info/business-economy-euro/economic-and-fiscal-policy-coordination/financial-assistance-eu/funding-mechanisms-and-facilities/sure_en

Verwey, M and A Monks (2021), “The EU economy after COVID-19: Implications for economic governance”, VoxEU.org 1 October.

[1] https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?qid=1591119459569&uri=CELEX%3A52020DC0123

[2] Support to mitigate Unemployment Risks in an Emergency (SURE).

[3] The European Commission has also helped to counter the socio-economic impact of the pandemic by putting in place the most flexible state aid rules ever in the EU to save jobs and companies. Moreover, at the Community level, the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) and the European Investment Bank (EIB) moved to make additional support facilities available.

[4] https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/economy-finance/com_2018_335_en.pdf

[5] „Growth-friendly“ is an often used notion albeit lacking a precise definition. Broadly speaking, it refers to a preference of investment (including in human and social capital) over consumption on the expenditure side, and taxation of consumption and (immovable) wealth rather than of factors of production such as labour and capital on the revenue side.

About the article

ISSN 2305-2635

The views expressed in this publication are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Austrian Society of European Politics or the organisation for which the author is working.

Keywords

EU, fiscal rules, Recovery and Resilience Facility, Stability and Growth Pact, NextGenerationEU, COVID-19

Citation

Pichelmann, K. (2022). Returning to a “new normal”: revising the EU fiscal rulebook. Vienna. ÖGfE Policy Brief, 02’2022