Policy Recommendations

-

- The net position with regard to contributions to and transfers received from the EU budget should be complemented by a comprehensive indicator capturing the benefits of EU membership.

- Reforms in the EU system of own resources through substituting a substantial share of national contributions by innovative own resources may also help to overcome the net position thinking.

- Increasing the EU added value provided by EU expenditures via providing more European public goods would contribute further to alleviate member states’ net position thinking

Abstract

Focusing primarily on the question of net contributions to the EU budget instead of the question of the ideal size and structure of an EU budget in order to master the common grand challenges is a major obstacle to the negotiations for the next Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF) of the EU. Moreover, this pattern is also an impediment to the current negotiations of the EU COVID-19 recovery fund. A quick solution that helps to overcome the net position thinking prevalent in many EU member states is desirable, as the current crisis is evolving rapidly and common action via European public goods could offer relief. Moreover, it is often neglected that particularly the net contributing countries have large gains e.g. from trade and investment in the EU’s single market. Complementing net positions by a comprehensive indicator capturing the benefits from EU membership may help to overcome member states’ net position thinking. Also, reforms within the MFF would be helpful: Increasing the EU added value provided by EU expenditures via providing more European public goods as well as reforms in the EU system of own resources substituting a substantial share of national contributions by innovative own resources.*)

*) This policy brief provides a brief summary of a forthcoming study for the European Parliament (Bachtrögler et al., 2020a).

****************************

Overcoming the net position thinking in EU member states

Problems and limitations associated with net position thinking

When assessing the benefits the member states receive from the EU budget, they primarily focus on their individual net positions (net operating balances), i.e. the net balance between their national contributions and the transfers received from the EU budget, instead of focusing on maximising the benefits the EU budget may generate for the EU as a whole and therefore for its individual members. The net position thinking thus represents an obstacle for a future-oriented EU budget because it diverts the member states’ attention from long-term challenges the EU has been facing, such as climate change, migration, digital change or persistent regional and income distribution inequalities. Focusing on the net positions leads to the design of an EU budget whose neither structure nor volume are adequate to cope with these challenges. In terms of structure, agriculture and cohesion spending have been dominating the Multiannual Financial Frameworks (MFF) and this trend continues in the proposal for the next MFF. In terms of volume related to the EU gross national income (GNI), the budget available to the EU has been shrinking for a long period of time (Schratzenstaller, 2019).

The net position thinking thus represents an obstacle for a future-oriented EU budget because it diverts the member states’ attention from long-term challenges the EU has been facing, such as climate change, migration, digital change or persistent regional and income distribution inequalities.

Moreover, net position thinking fuels demands for rebates by net contributing countries to limit their negative net positions. The rebates make the EU’s financing system complex and non-transparent and violate the ability-to-pay-principle. In addition, they are not systematically linked to the size of member states’ net positions and are not awarded to all net contributing member states. Last but not least, the net position thinking exacerbates negotiations on the MFF, making an agreement more and more difficult to reach. This in turn leads to delays in establishing the MFF for the next seven-year period, which might impede implementation of various EU programmes.

There are a number of benefits accruing to the member states from EU membership beyond the pure financial streams, which are completely neglected by the net positions. EU policies coordinated and financed by the EU are replacing or complementing individual member states actions, creating additional European added value that is not captured in the net positions.

In addition, net positions do not tell anything about the structure of transfers received by individual member states from the EU budget and about their effectiveness and outcomes. For instance, Bachtrögler et al. (2020b) point out that employment and productivity effects of funding for industrial firms from the cohesion funds vary between regions and member states, which is, however, not captured in net positions.

The focus of net positions also excludes indirect benefits from the EU budget that might accrue to member states. According to our own analysis, parent companies based in the more developed member states may indeed indirectly profit considerably (e.g. through internal settlements within the corporate group) from European Regional Development Fund co-funding provided for investments of their subsidiary firms in cohesion countries. There are also a number of positive externalities accruing to EU15 member states. These externalities result from the support of entrepreneurship and innovation, transport infrastructure, universities, and environmental protection through cohesion policy in the V4 countries (Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia).

Finally, net positions do not capture benefits from expenditures going to third countries outside the EU such as development aid or accession support, which might yield indirect benefits for member states.

Benefits of membership to the European Union

The EU is more than the sum of the member states, and the economic impacts of EU policies go far beyond the rather limited narrative of the net financial contributions. More specifically, the EU allows for the provision of a large number of public goods, including the European Single Market which ensures the free movement of goods, services, capital and labour, which member states cannot ‘produce’ by themselves. Several benefits accrue to the member states through EU membership, including particularly benefits of intra-EU direct investments and intra-EU trade.

The EU is more than the sum of the member states, and the economic impacts of EU policies go far beyond the rather limited narrative of the net financial contributions.

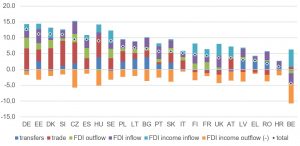

We therefore suggest an alternative indicator for the benefits of (EU) integration, which should replace or at least complement the indicator of the net contributions to the EU budget with all its limitations. The net transfer figures as measured in % of GDP should be amended with the following additional sub-indicators: i) the trade balance of goods and services in % of GDP; ii) the FDI inflows (officially termed as liabilities) in % of GDP; iii) the FDI outflows (officially termed as assets) in % of GDP; and iv) the repatriated FDI income inflows in % of GDP. From this sum we subtract v) the repatriated FDI income outflows in % of GDP.

Generally, the EU supports the free flow of FDI within and across the EU borders.

Achieving a positive balance of goods and services trade allows economies suffering from unemployment to expand their productive capacities in the process of global division of labour. The EU is a strong advocate and supporter of the creation of trade surplus with the help of its trade (and indirectly also with its take on macroeconomic) policy. Both the inflow as well as the outflow of FDI can generate important advantages for the home and host countries: via the incoming flow of capital and technological knowledge for host countries and as the basis of specialisation in higher value-added segments of production and future streams of profit inflows for home countries. Consequently, the inflow of repatriated FDI income is a welcome profit revenue, while the outflow of repatriated FDI income can be seen as an undesirable but necessary repayment of earlier capital influx and is therefore subtracted from the above sub-indicators sum[1], thus entering the equation with a negative sign. Generally, the EU supports the free flow of FDI within and across the EU borders.

We construct the indicator for seven-year averages, following the period of the EU’s Multiannual Financial Framework and in order to smooth out the data (most recent period depicted in Figure 1). Due to extreme (mostly positive) values we exclude a group of countries that are widely seen as tax havens, where capital flows are not necessarily related to the domestic real economy, but predominantly to financial transactions, often stemming originally from other countries. These include Cyprus, the Netherlands, Ireland, Luxembourg and Malta (Belgium might be a candidate as well).

The gains from integration are rather small, particularly in some of the peripheral EU member states in Southeast Europe. There, EU transfers and FDI inflows are the most important sources of benefits from integration, while net trade and FDI income outflows weigh negatively. This is very different from some of the more centrally located EU economies, where it is particularly the surplus in goods and services trade that has the biggest impact, which are at around 10% of GDP annually. For economies in the upper segment of the overall indicator, FDI outflows and FDI income inflows also contribute significantly.

Contrary to the net contributions to the EU budget, integration is not a zero-sum game for EU economies, but additional value is created by the international division of labour with a bigger market for all member states.

Figure 1: Benefits of integration for selected EU member states, 2013-2019, in % of Gross Domestic Product

Source: EC, Eurostat, own calculations.

Overall, and neglecting the tax haven countries, average annual gains from integration in EU economies are at about 6% of GDP in recent years. This is particularly due to strong average trade surpluses (2.4%) as well as FDI inflows (2.1%), reduced quite significantly by FDI income outflows (2.6%). Average EU net transfers (1.3%) as well as FDI outflows (1.3%) and FDI income inflows (1.7%) are of smaller importance. Overall, the above exercise shows that contrary to the net contributions to the EU budget, integration is not a zero-sum game for EU economies, but additional value is created by the international division of labour with a bigger market for all member states.

Approaches to overcome the net position view

There are several reform options within the EU budget addressing its various structural features that could help to overcome the net position thinking. Increasing the EU added value provided by EU expenditures would contribute to alleviate the member states’ net position thinking. The higher the share of expenditures dedicated to European public goods characterised by cross-border benefits and/or providing efficiency gains compared to national provision, the less meaningful the concept of net positions would be, as benefits from these public goods accrue to the EU as a whole and thus to all member states together.

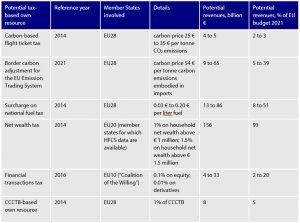

Reforms in the EU system of own resources is another option. Substituting a substantial share of national contributions to the EU budget by innovative (tax-based) own resources may loosen the link between payments into the EU budget on the one hand and transfers received out of it on the other. Table 1 presents several options for innovative own resources. They could be introduced within a coordinated move by member states based on the current treaties without granting tax sovereignty to the EU. The less their revenues are attributable to individual member states due to cross-border aspects and the larger the share of national contributions they would replace, the less meaningful net operating balances would be.

Moreover, all these options could contribute to fair and more sustainable taxation in the EU. Several of them may particularly support the implementation of the European Green Deal as “green own resources”: a carbon-based flight ticket tax (or aviation taxes in general), a border carbon adjustment mechanism for the EU Emission Trading System, or a surcharge on national fuel taxes. Within a supra-national tax shift innovative own resources could replace national contributions; which could create additional fiscal space for member states urgently needed in the aftermath of the current COVID-19 crisis. They could also serve to finance common EU-wide recovery measures (see e.g. Creel et al., 2020) after having overcome the acute crisis or to fund a larger EU budget.

Table 1: Options for tax-based own resources and potential tax revenues

Source: Schratzenstaller and Krenek (2019), table 2 (slightly modified).

The focus on net positions fuels demands for rebates by net contributing member states to limit negative net positions. Keeping some kind of a (reformed) rebate system for the time being may therefore help to mitigate the net position thinking and reach a compromise.

Overall, the operating budgetary balance has a number of failures and limitations, and belonging to the EU, notwithstanding the status of the member states’ operating budgetary balance, brings about many positive outcomes ranging beyond the pure financial streams. Therefore, net positions should rationally be considered as accounting indicators only, instead of indicators to capture the direct and indirect benefits from the EU budget.

- Bachtrögler, J., R. Blomeyer, D. Hanzl-Weiss, M. Holzner, G. Hunya, V. Kubeková, O. Reiter, M. Schratzenstaller, R. Stehrer, R. Stöllinger (2020a), ’How EU funds tackle economic divide in the European Union‘, study requested by the BUDG Committee of the European Parliament.

- Bachtrögler, J., Fratesi U. and Perucca, G. (2020b), The influence of the local context on the implementation and impact of EU Cohesion Policy, Regional Studies, 54(1), pp. 21-34.

- Creel, J., M. Holzner, F. Saraceno, A. Watt, J. Wittwer (2020), ‘How to Spend it: A Proposal for a European Covid-19 Recovery Programme’, wiiw Policy Note, No. 38.

- Schratzenstaller M. (2019), Strengthening added value and sustainability orientation in the EU budget, in Nowotny E., Ritzberger-Grünwald D., Schuberth H. (eds.), How to finance cohesion in Europe?, Cheltenham: Edgar Elgar, pp. 92-105.

- Schratzenstaller M., Krenek A. (2019), Tax-based own resources to finance the EU budget, Intereconomics, 54(3), pp. 171-177.

ISSN 2305-2635

The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Austrian Society of European Politics or the organisation for which the authors are working.

Keywords

EU budget, Multiannual Financial Framework, own resources, EU membership, Cost of Non-Europe, EU added value, FDI, trade

Citation

Bachtrögler-Unger, J., Holzner, M., Kubeková, V., Schratzenstaller, M. (2020). Overcoming the net position thinking in EU member states. Vienna. ÖGfE Policy Brief, 19’2020