Policy Recommendations

- Progress in the democratisation of pre-accession countries has directly benefitted their EU accession path; therefore, stronger EU support for the democratisation of candidate countries should lead to more progress within the EU accession process.

- The EU and its member states need to step up efforts and commit to internal coherence to improve their credibility and external projection as a democratisation actor. This includes increasing efforts to advocate for enlargement internally.

- A concrete accession date combined with a strong conditionality would help reset the EU enlargement process in the Western Balkans.

Abstract

This Policy Brief claims that the EU pre-accession process in the Western Balkans needs stronger political support for democratisation by the European Union (EU) and its member states. Only progress on the democratisation path can lead to a successful and sustainable transformation of the EU candidate countries. Once EU accession negotiations are opened, the EU should keep its monitoring and involvement at a high level, since as long as the accession perspective is not underlined with a realistic accession date, the processes are becoming a bureaucratic window dressing exercise.

****************************

How to support democratisation in the Western Balkans?

Introduction

In March 2023, the 2nd virtual edition of the global “Summit for Democracy” took place, gathering more than 100 countries for reinforcing the ambition to fight authoritarianism, corruption, and advancing the respect for human rights in a global perspective. With the Summit for Democracy, initiated in 2021, the U.S. seeks to “renew democracy at home and abroad” in a period of a global decline of democracy and rising authoritarianism.[1] In his contribution to the March Summit, EU Council President Charles Michel underlined that there needs to be “more engagement, more listening, and more concrete action to support the countries in their journeys towards prosperity and democracy”.[2] It seems that the European Union (EU) follows problem identification and the need for a more assertive approach with regards to support for democratisation. To what extent is this reflected in the support schemes for democratic development in the EU’s near neighbourhood? And what are the perspectives for bottom-up democratisation in the countries of the Western Balkans that are candidates for EU accession and in the focus of a transformative process induced by the enlargement policy? This Policy Brief sheds light on the EU’s current approach towards democratic processes in the region and suggests ways forward on how the EU and its member states can better support these processes. Fostering democratisation from below should be a core interest of the EU and needs facilitating measures from above.

Democratic progress and backsliding in the Western Balkans

Over the last 20 years since the Thessaloniki Summit, during which the European Perspective was granted to the Western Balkans, democratic developments in the six countries have been uneven and characterised by both democratic progress and democratic decline in each of the countries. These developments have been tracked by different democratisation indices that help to quantify and visualise the trends over time and along specific indicators, such as the Global State of Democracy (GSoD) Indices by the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (International IDEA) or the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Report.[3] The GSoD Index classifies countries into five categories: “high performing democracies”, “mid-range performing” and “weak democracies”, “hybrid regimes”, and “authoritarian regimes”. According to the latest edition of the GSoD Report 2022, none of the WB countries are classified as “high performing” nor as clear cut “authoritarian”. Kosovo, Montenegro, and North Macedonia are falling into the category of “mid-range performing democracies” while Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina are considered “weak democracies”, and Serbia is the only “hybrid regime” in the region.[4] In terms of tendencies, two countries stand out in a positive and negative way over a ten-year period. Kosovo made the most significant progress in three out of five indicators, and Serbia experienced the highest share of decline in all five indicators.[5]

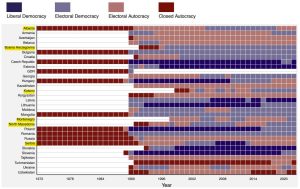

The V-Dem Democracy Report (2023) rates the six countries slightly differently according to four categories: “Liberal Democracy”, “Electoral Democracy”, “Electoral Autocracy” and “Closed Autocracy”. None of the countries is considered in the highest category as a “Liberal Democracy” and neither is considered in the lowest category as a “Closed Autocracy”. Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, Montenegro, and North Macedonia are classified as “Electoral Democracies”, whereas Albania and Serbia are considered in the lower category of “Electoral Autocracies”.[6] The table below shows the democratic development in Eastern Europe (and Central Asia) over the last three to five decades.

Each change in category is a result of concrete political developments and decisions that also had an impact on the pace of the EU approximation path of the respective countries.

Interlinkage between the EU approximation process and democratic reforms

The then-hidden costs of non-acting, however, are becoming visible with an assertive Serbia, that threatens Kosovo and still partners with a war-crime-committing Russia.

Improvements in the democratic performance of the WB6 countries have usually directly benefitted their EU integration path. The fact that Serbia opened EU accession negotiations in 2014 can be considered a result of a phase of “liberal democracy” in the years 2007–2014, preceding a phase of “electoral democracy” from 2001 on with the tenure of Zoran Đinđić who was the first democratic, post-communist prime minister of Serbia, and had been one of the leaders of the democratisation movement. This democratic phase ended with the election of Aleksandar Vučić as Prime Minister in 2014. With a lack of clear accession perspective and the announcement by EU Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker in 2014 to have a break in the enlargement process for at least five years, the EU lost its leverage too.[7] But not only did the enlargement process lose transformative effect, the EU and its member states stood by and watched how the democratic decline took place, without taking serious counteracting measures. Nearly ten years later, Serbia has become a “captured society”, as the most recent Helsinki Committee Report 2022/2023 concludes.[8] The then-hidden costs of non-acting, however, are becoming visible with an assertive Serbia, that threatens Kosovo and still partners with a war-crime-committing Russia. In light of the recent protest against the autocratic regime of Vučić, it is a pity, that the EU is not clearly articulating support for the democratic claims of the population.[9]

North Macedonia and Kosovo were the two countries that made progress on their democratic development paths, despite the less encouraging prospect of EU accession. North Macedonia managed to overcome a period of state capture by former Prime Minister Nikola Gruevski and his VMRO-DPMNE Party (Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization – Democratic Party for Macedonian National Unity) in 2016. It solved the neighbourly dispute with Greece, changed its name, and acceded to the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) in 2020. Still, it sees its EU approximation process blocked by Bulgaria on the grounds of identity questions. This stands in contradiction to the EU values of respect for the cultural identities of its member states. The political blackmailing of acceding countries by its neighbour countries should be avoided by all means in a concerted effort by all other member states, as it is undermining the credibility of the EU as a whole. North Macedonia officially started accession negotiations with the EU in 2022 but still has to amend its constitution in order to introduce the Bulgarian population as an official minority, as per an agreement facilitated by France. Although the EU has been communicating this compromise as a breakthrough, the chances for a constitutional change are currently bleak; hence, this “deal” could lead to another deadlock for North Macedonia.

North Macedonia and Kosovo were the two countries that made progress on their democratic development paths, despite the less encouraging prospect of EU accession.

Kosovo has experienced democratic consolidation since 2014 and has recently made visible progress in the area of rule of law under Prime Minister Albin Kurti. It has the most pro-European population among the EU candidate countries[10] and has attracted a spike in foreign direct investments due to its improved business environment and the stronger stance of the Kurti government against corruption.[11] After years of stagnation in the field of rule of law, the positive developments led to Kosovo officially applying for EU membership in December 2022, and from January 2024, its citizens will profit from visa liberalisations. Its ambition to extend its sovereignty towards the northern part, following the municipal elections, has been sanctioned by the EU, despite the destabilising (re)actions by Serbian proxies. In order to regain control over the situation, the EU missed an opportunity to exert pressure on Serbia to stop its destabilising activities. Clear support for Kosovo that is committed to further democratisation is needed and should be the leading narrative in this situation.

Achieving a milestone in the EU accession process, notably starting the EU accession negotiations, did not have a long-lasting effect on the democratic developments in Montenegro.

After starting accession negotiations in 2012, a democratic decline occurred in Montenegro, which went from “Electoral Democracy” to “Electoral Autocracy”. Achieving a milestone in the EU accession process, notably starting the EU accession negotiations, did not have a long-lasting effect on the democratic developments in Montenegro. Nearly a decade later, Montenegro has seen an end to the long-term ruler Milo Đukanović, whose party, the DPS first lost government power in 2020, followed by his own defeat in the presidential elections in March 2023. The new pro-European party “Europe now” has won the parliamentary elections in June 2023, and with the new president, Jakov Milatović, Montenegro could see further progress on its democratisation and EU integration path. The EU should use the opportunity to revive the accession negotiation process and use the new methodology, including its reversibility, should a new government not deliver on democratic reforms.

On the one hand, Albania has been recognised for its judicial reform process, on the other hand, the democracy index still classifies Albania as an “Electoral Autocracy”.

The same applies to Albania, which started EU accession negotiations formally in 2022 together with North Macedonia. On the one hand, Albania has been recognised for its judicial reform process, on the other hand, the democracy index still classifies Albania as an “Electoral Autocracy”. The EU should not make a similar mistake as in Serbia and instead prioritise a genuine democratisation of the Albanian political system over the alleged stability of a more autocratically governed Albania under Edi Rama. Its clear foreign policy alignment and pragmatic regional policy should not prevent the fact that grassroots democratic actors should be supported by the EU.

In terms of democratisation policy, the EU should implement effective sanctioning policies towards actors that seek to undermine the Dayton agreement and pose a threat to the country’s sovereignty and territorial integrity.

Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH) received EU candidate status in December 2022, which was a political signal of support for the country in light of the Russian aggression against Ukraine and the successive granting of candidate status to Ukraine and Moldova in June 2022. In terms of democratisation policy, the EU should implement effective sanctioning policies towards actors that seek to undermine the Dayton agreement and pose a threat to the country’s sovereignty and territorial integrity. Milorad Dodik’s recent attack on the competence of the Constitutional Court of BiH is a case in point.[12] The EU should flank its support for democratisation with clear political measures and further increase its security presence on the ground. While trying to pursue a civic rights-based democratisation policy, the EU should be led by the logic of supporting the representatives of the victims of the wars in the 1990s.

The EU should flank its support for democratisation with clear political measures and further increase its security presence on the ground.

A new momentum for democratisation?

With the granting of the EU membership perspective to Ukraine, Moldova, and Georgia, the EU seems to have created a new enlargement momentum.[13] Besides the fact that the accession perspective has been linked to a prior EU internal reform by German Chancellor Olaf Scholz, which could raise scepticism regarding the materialisation of enlargement, it is primarily the enthusiasm of the population in Ukraine, Moldova, and Georgia and the governments of Moldova and Ukraine that show the willingness for reform and have revived the process. The reactions from the WB region are understandably less enthusiastic after 20 years of unfulfilled promises, and vary between scepticism, perception of competition with the new candidate countries, and entitlement to be the first in the row to accede. The political elite is reluctant to pursue immediate serious reforms in the sphere of the rule of law when the benefits of EU membership are still not linked to a clear accession date. What should the EU and its member states do to re-energise the process? They should, on the one hand, focus on supporting genuine grassroots pro-European actors and, on the other hand, increase the pressure on governments to enable democratic participation. They should clearly side with the pro-European population to show their support. The negative conditionality of the Instrument for Pre-accession Assistance (IPA) III funds should be used, meaning the possibility of adjustment or even suspension of funds in the case of a significant decline or continued lack of progress in fundamental areas, including the fight against corruption, and organised crime, and media freedom. Furthermore, as a recent report from the Democratization Policy Council (DPP) suggests, EU aid to governments should be transparent and reviewable by citizens, and the support programmes for civil society should not depend on changing donor funding trends but include a bottom-up programming process in which civil society and ordinary citizens are involved in the priority setting.[14] This would increase the coherence of the struggle for democratisation and reduce the perception of civil society organisations as actors that are disconnected from the population. The EU and its member states should always side with the pro-EU majorities in the populations until they are able to “generate sufficient electoral momentum to bring to power reformist leaders”.[15] Finally, the EU and its member states are also responsible for advocating internally for the acceptance of another EU enlargement round. As long as the internal message to EU citizens is not coordinated and convincing, the external projection of a transformative effect will remain weak. A concrete accession date combined with a strong conditionality would help reset the EU enlargement process in the Western Balkans.

****************************

[1] Whitehouse (2023). FACT SHEET: The Biden-Harris Administration’s Abiding Commitment to Democratic Renewal at Home and Abroad. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2023/03/29/fact-sheet-the-biden-harris-administrations-abiding-commitment-to-democratic-renewal-at-home-and-abroad/

[2] European Council (2023). Written contribution by European Council President Charles Michel to the Summit for Democracy 2023, 29 March 2023. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/63455/230329-logo-summit-for-democracy-written-contribution.pdf

[3] V-Dem Institute. Democracy Reports. https://www.v-dem.net/publications/democracy-reports/; The Global State of Democracy Initiative. https://www.idea.int/gsod/

[4] Gentiana Gola (2022). Where do Western Balkan countries really stand on democratic performance? https://www.idea.int/blog/where-do-western-balkan-countries-really-stand-democratic-performance

[6] Evie Papada et al. (2023). Defiance in the Face of Autocratization. Democracy Report 2023. University of Gothenburg: Varieties of Democracy Institute (V-Dem Institute), p. 40. https://v-dem.net/documents/29/V-dem_democracyreport2023_lowres.pdf

[7] Maja Poznatov (2014). Serbia grudgingly accepts Juncker’s enlargement pause.

[8] Sonja Biserko et al. (2023). Helsinki Committee Report 2022/2023, Helsinški Committee for Human Rights in Serbia. https://www.helsinki.org.rs/doc/Report2022.pdf

[9] Snezana Rakic (2023). EU’s latest report on Serbia – No mention of protests, Serbian Monitor, 14.06.2023. https://www.serbianmonitor.com/en/eus-latest-report-on-serbia-no-mention-of-protests/

[10] European Western Balkans (2021). Public Opinion Poll in the Western Balkans on the EU Integration. 8 November 2021. https://europeanwesternbalkans.com/2021/11/08/public-opinion-poll-in-the-western-balkans-on-the-eu-integration/

[11] CEIC Data (2022). Kosovo Foreign Direct Investment 2009-2022. https://www.ceicdata.com/en/indicator/kosovo/foreign-direct-investment

[12] Azem Kurtic (2023). Bosnia’s Serb Entity Passes Law Rejecting Constitutional Court’s Authority, 28 June 2023, Sarajevo. https://balkaninsight.com/2023/06/28/bosnias-serb-entity-passes-law-rejecting-constitutional-courts-authority/

[13] Ian Bancroft (2023). Is There Really New Momentum Behind EU Enlargement? https://balkaninsight.com/2023/03/13/is-there-really-new-momentum-behind-eu-enlargement/

[14] Kurt Bassuener et al. (2023). Gaslighting Democracy in the Western Balkans: Why Jettisoning Democratic Values is Bad for the Region and the Liberal World, DPC Policy Paper, Sarajevo, Brussels, Berlin. http://www.democratizationpolicy.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/DPC-Policy-Paper_Gaslighting-Democracy.pdf

[15] Dimitar Bechev (2022). What Has Stopped EU Enlargement in the Western Balkans? Carnegie Europe, published 20 June 2022. https://carnegieeurope.eu/2022/06/20/what-has-stopped-eu-enlargement-in-western-balkans-pub-87348

About the article

ISSN 2305-2635

The views expressed in this publication are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Austrian Society of European Politics or the organisation for which the author is working.

Keywords

Western Balkans, democratisation, EU accession, progress, backsliding

Citation

Maugeais, D. (2023). How to support democratisation in the Western Balkans? Vienna. ÖGfE Policy Brief, 23’2023