Policy Recommendations

- The EU needs a self-confident and loud European Parliament – especially in times of crisis. It should actively shape the European discourse and further promote European integration with creative ideas.

- The European Parliament should exert public pressure even more explicitly, if democratic values as well as the EU as a legal community are called into question.

- It should use its right of legislative initiative and demand empathically what the President of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen, promised in her first speech in front of the plenary of the European Parliament, namely a reform of the EU electoral law with an improved “SpitzenkandidatInnen process” as well as the introduction of transnational electoral lists for the next European elections.

Abstract

The ninth elections to the European Parliament took place from 23-26 May 2019. Given the increased turnout, the European Parliament emerged democratically strengthened from the European elections 2019. Nevertheless, the stronger fragmentation of the present EU Parliament – and thereby even more difficult majority finding – impairs its capacity to act and weakens the role of the Parliament in the interinstitutional structure of the EU. Although the European elections were framed as “choice of destiny” in advance, the predicted political earthquake did not occur. The eurosceptic and right-wing political forces could record a clear vote increase but the EU integration friendly forces were able to keep the majority in the new EU Parliament. Nevertheless, there were changes in the political structure of the EU. The grand coalition between the European People`s Party (EPP) and the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats (S&D) was deselected. Trend-setting decisions cannot be taken single-handedly by the two parliamentary groups any longer. They require the cooperation of the Liberals and the Greens. In addition, nearly 60 percent of all Members of the European Parliament are new and there was a considerable shift of forces within the European political groups. The bypassing of the “SpitzenkandidatInnen process” has been a first backlash from the point of view of democratic politics.

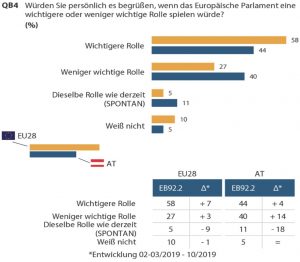

The Austrians` opinion about the European Parliament used to be more positive in the past. In comparison to the EU average (58%), significantly less people (44%) are of the opinion that the European Parliament should play a more important role in the future. Anyway, the negotiations for the next Multiannual Financial Framework (2021-2027) will be the next possibility to show how capable of acting and assertive the new European Parliament actually is.

****************************

The European Parliament – One year after the European elections

Introduction

The ninth elections to the European Parliament took place from 23-26 May 2019. In the first year of the ninth legislative period, the new EU Parliament is confronted with two decisive incidents: Brexit and the coronavirus pandemic.

After a long time of negotiations and political tug-of-war, the United Kingdom left the EU on 31 January 2020. Since mid-March, the European Union has been in crisis mode due to the outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic. Against this background, the current Policy Brief examines the political composition of the new EU Parliament one year after the European elections, the impact the new balance of power has on the interinstitutional relations of the EU and the role the still young Parliament can actually play. In addition, the analysis takes account of the attitude of Austrians` towards the European Parliament.

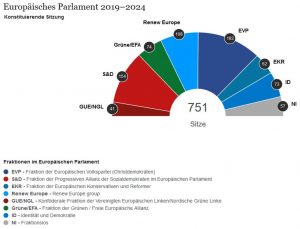

The elections to the European Parliament 2019

Regarding voter turnout, the European elections brought pleasant results: In Austria, the turnout with 59,8 percent (plus 14,4 percentage points compared with 2014) was the highest since 20 years. For the first time since 1999, turnout climbed to 50,6 percent EU-wide (plus 8 percentage points).[1] The political composition of the European Parliament of the ninth legislative period (2019-2024) has changed significantly compared to the legislative period 2014-2019.[2] A grand coalition does not exist any longer. Although the Christian Democrats (EPP) and the Social Democrats (S&D) still rank the first (2019: 182 mandates/2014: 216 mandates) and the second place (2019: 154 mandates/2014: 187 mandates), they both have lost votes and do not constitute an absolute majority in the European Parliament any longer.[3] The Liberals (Renew Europe)[4], the Greens (Greens/EFA) and the right-wing nationalist parliamentary group (ID) are among the winners of the election. The newly founded parliamentary group “Renew Europe” becomes the third strongest force in the European Parliament with 108 mandates (ALDE 2014: 69 mandates). The Greens take fourth place with 74 mandates (2014: 52 mandates), closely followed by the new right-wing nationalist parliamentary group “Identity and Democracy” (ID) with 73 mandates[5] (ENF 2014: 36 mandates). The parliamentary group “European Conservatives and Reformists” (ECR) are in sixth place after losing 62 mandates (2014: 77 mandates). The Confederal Group of the European United Left/Nordic Green Left (GUE/NGL) lost votes too and takes seventh place with 41 mandates (2014: 52 mandates). 57 Members of the European Parliament do not join any parliamentary group at all.[6]

EU-wide turnout rose up to 50,6 percent for the first time since 1999 – an increase of about 8 percentage points.

Chart 1

Source: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/election-results-2019/en

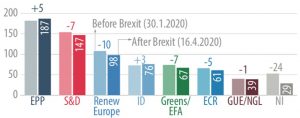

The composition of the European Parliament after Brexit

After the United Kingdom left the EU on 31 January 2020, the number of seats in the European Parliament was reduced from 751 to 705. A part of the British mandates (27 out of 73) was distributed among 14 member states, which had an impact on the majority and power relationships in the European Parliament. Especially the EPP is among the winners of Brexit, gaining five mandates and further extending its lead to the second strongest political force, the S&D. ID also gained three additional mandates, replacing the Greens/EFA (minus seven mandates) as fourth strongest force. Among the losers of Brexit are, apart from the Greens, the parliamentary group “Renew Europe” (minus ten mandates), S&D (minus seven mandates) but also ECR (minus five mandates) (see chart 2). The non-attached Members of Parliament lose altogether 24 mandates.

Chart 2

Source: European Parliamentary Research Service (April 2020): Members of the European Parliament from February 2020

On trend, Brexit weakened the centre-left groups (S&D, Greens/EFA, Renew Europe, GUE/NGL) and strengthened the center-right groups (EPP, ID).

With 39,5 percent, the proportion of women in the European Parliament is as high as never before.[7] The new Parliament is also younger than before: The average age of the MEPs is 50 years.[8] The proportion of new members is relatively high as well, with approximately 59 percent.[9]

Austria in the new European Parliament

Of the originally 18 Austrian MEPs[10], 12 entered Parliament for the first time. After Brexit, Austria received in addition a further MEP – who was already MEP in the legislative period 2014-2019.[11] With one Vice-President (Othmar Karas/EVP), one committee chair (Evelyn Regner/S&D, Committee of Women`s Rights and Gender Equality), as well as two deputy chairs in the subcommittee of Human Rights (Karoline Edtstadler/EPP[12]) and in the subcommittee of Security and Defence (Lukas Mandl/EPP), Austria could gain leading positions in the European Parliament. However, no one of the Austrian MEPs is a member of an executive committee of the parliamentary groups, the inner circle of policy making in the European Parliament.[13]

The preliminary end of the “SpitzenkandidatInnen process”

According to the Treaty on European Union, the European Parliament is significantly involved in the appointment of the President of the European Commission.[14] In the European elections 2014, the European political parties agreed for the first time to appoint only lead candidates for the position of the President of the European Commission, who were lead candidates of their political parties during the European election campaign. The aim was to limit the scope of the European Council regarding its right to propose a candidate for the President of the European Commission, to increase the importance of the European elections as well as the Parliament`s own influence.[15] After the European elections 2014, the lead candidate of the party with the most votes, Jean-Claude Juncker (EPP), was nominated by the European Council and afterwards elected by the European Parliament. The “SpitzenkandidatInnen procedure” had successfully passed the test.

As a result, most European parties appointed lead candidates before the European elections 2019. Also this time, the parties agreed that only a candidate, who had run in the European election campaign as lead candidate of one of the parties, would be accepted as candidate for the presidency of the Commission. Though most EU member states were sceptical with regard to the “SpitzenkandidatInnen procedure” and refused its institutionalisation.[16] Contrary to the European elections 2014, the MEPs were not able to agree on a candidate: The EPP with its lead candidate Manfred Weber took first place, the S&D ranked the second with its lead candidate Frans Timmermans. In the European Council, no multi-party consensus was on the horizon. The missing ability to find a compromise in the European Parliament finally allowed the EU Heads of States and Governments to unanimously nominate the former German minister of defense, Ursula von der Leyen, as candidate for the presidency of the European Commission. Von der Leyen had never been lead candidate during the European election campaign.

To convince the European Parliament, von der Leyen made a multitude of promises in her application speech in front of the plenum. She promised to strengthen European democracy, to reform the EU electoral law and to improve the “SpitzenkandidatInnen process” and enhance its visibility for voters in the future. Furthermore, she considered the introduction of transnational electoral lists for the next European elections. Apart from that, von der Leyen also argued for a de facto right of initiative[17] of the European Parliament and obliged the Commission to react with a correspondent legislative proposal, if the majority of the Parliament asks for it.[18] All these proposals should be further developed in the context of a conference about Europe`s future, where also citizens are supposed to participate.

Despite the renunciation of the “SpitzenkandidatInnen process”, the Members of the European Parliament elected Ursula von der Leyen into office on 16 July 2019.[19] The new Commission started work on 1 December 2019.

A fragmented European Parliament

The present European Parliament is more fragmented than the European Parliament of the past legislative period. Obtaining a majority is more difficult since the two dominant parliamentary groups, EPP and S&D, both lost votes and do not constitute an absolute majority for the first time since the first direct elections to the European Parliament in 1979. In the past legislative period, EPP and S&D still voted together in 73,4 percent of the votes.[20] In the present legislative period, the filling of EU leading positions, the adoption of the EU budget as well as other directional decisions regarding European legislation cannot be taken single-handedly by the two formerly dominant parliamentary groups any longer. At least three parliamentary groups need to find a common denominator.[21]

In total, the integration-friendly forces retain the majority in the new European Parliament, although this majority is more fragmented.

The groups to the right of the political spectrum (ID) have gotten stronger compared to the last legislative period. Nevertheless, the forecasted landslide victory of the eurosceptic and right-wing political forces never happened. In total, the integration-friendly forces retain the majority in the new European Parliament, although this majority is more fragmented. In addition, the right-wing populists in the ID have little influence, since they are isolated by the political center.[22] The ID did not get the position of one of the 14 Vice-Presidents, one of the 5 quaestors or one of the altogether 20 committee chairs respectively the 2 subcommittee chairs.[23]

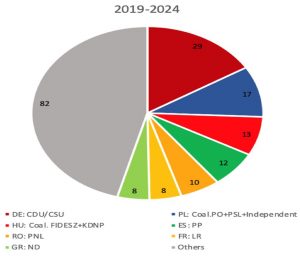

Strengthening versus weakening of national parties using the example of EPP and S&D

Although the EPP remained the strongest parliamentary group in the European Parliament, the number of its members has decreased. Primarily, this is attributed to the losses of votes of its member parties in France, Italy, Poland and Spain. In other EU member states, the member parties of the EPP grew stronger, for instance in Greece, Austria and Hungary.[24] The German MEP Manfred Weber (CSU) was reelected as chair of the EPP. Despite of loss of votes, the German CDU/CSU and the Polish PO/PSL/Independent are currently the strongest national parties in the EPP. The Hungarian FIDESZ/KDNP takes third place (see chart 3).

Chart 3

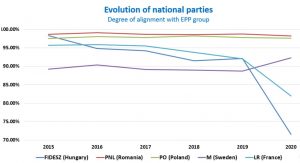

With regard to the voting behavior during the first six months after the European elections, the CDU/CSU, the Romanian PNL and the Polish PO were predominant and determined the party line of the EPP. In contrast, the Hungarian FIDESZ and the French Les Républicains (LR) voted more often against the party line (see chart 4). The decreasing influence of the French LR-delegation is remarkable because its predecessor UMP was one of the biggest national delegations in the EPP during the former legislative period.[25] The poor performance of the LR in the European elections 2019 has diminished its influence in the EPP. Therefore, there is currently no real counter-weight to the CDU/CSU.[26]

Due to the suspension[27] of membership rights in March 2019, further affiliation of FIDESZ to the EPP was unsure. The suspension is still valid but so far no decision has been taken regarding an exclusion of FIDESZ from the EPP. In the first months of the recent legislative period, the MEPs of FIDESZ voted noticeably against the EPP party line. Their positions were more often congruent with the positions of ECR than their own parliamentary group. In the areas of migration, gender and education, FIDESZ even voted more often alongside the right-wing nationalist ID than the EPP.[28]

Chart 4

Source: Vote Watch (January, 2020): European Parliament: current and future dynamics

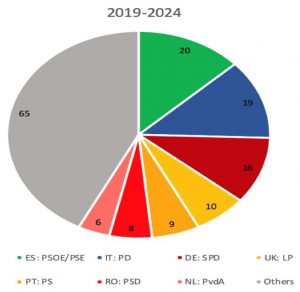

Despite heavy losses in votes, the S&D remained the second strongest force in the current European Parliament. Similar to the EPP, the loss of votes is primarily attributable to the poor performance of member parties in several big EU member states, for instance Germany, Italy, France and Romania. At the same time, in other EU member states member parties of the S&D could record significant increases in votes, especially in Spain and to a lesser degree also in Portugal and the Netherlands. Nevertheless, these increases could not compensate the overall losses of the S&D.[29] They lead to shifts within the parliamentary group, since the Spanish PSOE replaced the German SPD as strongest national party due to its election success.[30] Accordingly, the Spanish MEP Iratxe Garcia Perez (PSOE) was elected as chair of the S&D. Despite losses of votes, the second and third strongest national party in the S&D are the Italians (PD) and the Germans (SPD) (see chart 5).

Chart 5

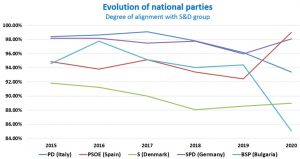

With regard to the voting behavior, one can notice an increase in accordance of the PSOE MEPs with the S&D party line (see chart 6). On the other hand, especially the Bulgarian BSP deviates from the S&D party line more and more often. This trend is probably attributable to domestic tensions as well as increasing differences between the national and the S&D leaders. Especially when it comes to questions of foreign policy as well as regarding environmental protection and climate change, the BSP deviates from the S&D party line, tending towards more USA critical positions in the first case respectively towards centre-right positions in the latter case.[31] But also the congruence of the Italian PD with the S&D party line is noticeably decreasing. The PD has shifted to the left, especially in the areas of budget and foreign policy, where the PD MEPs more often agree with the Greens than with Renew Europe.[32] In contrast to the EPP, there is no national party in the S&D, which has significantly more members than the other national parties.[33]

Chart 6

Source: Vote Watch (January, 2020): European Parliament: current and future dynamics

The Austrians` opinion of the European Parliament in comparison

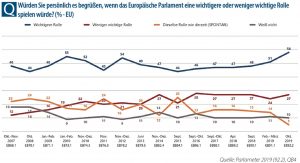

A few months after the European elections 2019, a majority of EU citizens stated that they advocate a stronger European Parliament. Since this question was posed in 2007 for the first time, this is the strongest support for a more influential European Parliament. 58 percent of Europeans demand a more important role for the European Parliament, an increase of 7 percentage points since spring 2019 and 14 percentage points since September 2015 (see chart 7).[34]

Chart 7

Compared to the EU average, significantly less Austrians ask for a more important role for the European Parliament in the future (only 44 percent). 40 percent were of the opinion, that the European Parliament should play a less important role (see chart 8).[35]

Chart 8

Source: Eurobarometer 92.2/Parlameter 2019 (October 2019): Austrian factsheet

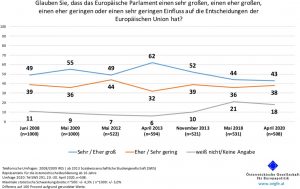

In November 2019, 41 percent of Austrians considered it to be realistic, that the European Parliament should have more influence regarding European laws in the future. On the other hand, 33 percent did not agree, 26 percent could not provide an assessment.[36] Also in November 2019, 55 percent of Austrians considered a reform of the European elections as well as the election of the President of the European Commission in the upcoming years as realistic. Only 22 percent regarded this as unrealistic. The number of Austrians who could not answer this question was quite large.[37] According to a recent survey[38] by the Austrian Society for European Politics (Österreichische Gesellschaft für Europapolitik / ÖGfE), Austrians are more sceptical with regard to the influence of the European Parliament on the European Union. In April 2020, only 43 percent were of the opinion that the European Parliament has a very/rather strong influence on the EU (38 percent respectively rather/very weak influence). This is the lowest number since the first collection of data in June 2008 (see chart 9).

Chart 9

Source: Surveys by telephone, SWS on behalf of ÖGfE, survey 2020: Tel SWS 291, 20-30 April 2020

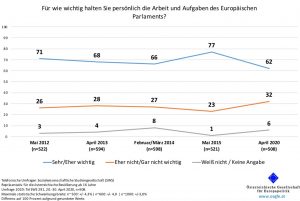

The work of the European Parliament is regarded by more than half of the Austrians (62 percent) as very/ rather important (32 percent rather unimportant/not important at all).[39] Nevertheless, this is also the lowest value since May 2012 (see chart 10).

Chart 10

Source: Surveys by telephone, SWS on behalf of ÖGfE, survey 2020: Tel SWS 291, 20-30 April 2020

Conclusions and outlook

Given the increased turnout, the European Parliament has emerged democratically strengthened from the European elections 2019. However, the non-compliance with the “SpitzenkandidatInnen procedure” presented a first democratic setback. The “SpitzenkandidatInnen procedure”, which was introduced for the first time at the European elections 2014, was supposed to strengthen the democratic representation of the EU citizens vis-à-vis the European Council. Finally, the opposite was the case. The EU Heads of States and Governments benefitted from the strong fragmentation of the recent European Parliament. The failure to reach a compromise as well as the fact that more than half of the MEPs are new in the Parliament, limits its capacity to act and weakens its role in the interinstitutional power structure of the EU.

The non-compliance with the ‘SpitzenkandidatInnen procedure’ presented a first democratic setback.

As a result of the European elections 2019, one can observe shifts within the parliamentary groups: Despite of loss of votes in the big EU member states, the German CDU/CSU and the Polish PO/PSL/Independent are currently the strongest national parties in the EPP. The Hungarian FIDESZ/KDNP takes third place. In the S&D, the Spanish PSOE replaced the German SPD as strongest national party due to its election success. Despite losses in votes, the second and third strongest national party in the S&D are the Italians (PD) and the Germans (SPD).

Brexit reduced the number of seats in the European Parliament and strengthened primarily the centre right parliamentary groups: EPP and ID. Among the losers of Brexit are the Greens, the Renew Europe group, the S&D group but also the ECR group and especially the non-attached MEPs.

Compared to the EU average, significantly less persons in Austria ask for a more important role for the European Parliament in the future.

The public opinion in Austria towards the European Parliament has been more positive in the past. Compared to the EU average (58 percent), significantly less Austrians (44 percent) demand a more important role for the European Parliament in the future. With regard to the influence of the European Parliament on the EU, Austrians are currently quite sceptical too. The same is valid for the work of the European Parliament. It is regarded by more than half of the Austrians (62 percent) as very/rather important. Nevertheless, this is the lowest number since May 2012.

Against this background it remains to be seen, if the promises of the President of the European Commission Ursula von der Leyen are actually implemented. A strengthening of democracy in Europe via a reform of the EU electoral law with an improved “SpitzenkandidatInnen process” as well as the introduction of transnational electoral lists for the next European elections would definitely benefit the European Parliament.

The new role of the European Parliament will also become apparent in the course of the negotiations for the next Multiannual Financial Framework (2021-2027).

The new role of the European Parliament will also become apparent in the course of the negotiations for the next Multiannual Financial Framework (2021-2027). These are the next tests for the Parliament, which traditionally enters negotiations with higher demands than the EU Heads of States and Governments respectively the European Commission. The Members of the European Parliament at the end of 2019 demanded an increase of the member states´ contribution to the EU budget to 1.3 percent of the EU-wide gross national income.[40] Against the background of the corona crisis, the original EU budget proposal of the Commission is currently being revised. With regard to the economic reconstruction of Europe, the MEPs demand more financial support and seem to be ready to use their right of veto, if they should not be met. Apart from a €2 trillion reconstruction and rescue package, they request a stockpiling of the EU`s Multiannual Financial Framework, in order to be able to overcome the corona induced economic recession.[41]

Whereas currently national interests dominate the European integration debate, the EU Parliament has so far lost negotiating power. Yet, the final balance can only be drawn at the end of the legislative period.

[1] https://www.europarl.europa.eu/election-results-2019/de (24.04.2020)

[2] After the European elections 2014, seven parliamentary groups were established. In the course of the legislative period, an eight parliamentary group (ENF) was formed.

[3] EP 2014: EPP and S&D = 412 seats, EP 2019: EPP and S&D = 336 seats (absolute majority = 376 votes)

[4] The parliamentary group „Renew Europe“ is a political alliance between the liberal political group ALDE of the EU Parliament of the 8th legislative period and Emmanuel Macrons alliance “Renaissance”.

[5] The new right-wing nationalist parliamentary group “Identity and Democracy” (ID) has emerged from the parliamentary group “Europe of Nations and Freedom” (ENF).

[6] Hrbek, Rudolf (2019): Europawahl 2019: neue politische Konstellationen für die Wahlperiode 2019-2014. In: integration 3/2019, p. 177.

[7] After Brexit https://epthinktank.eu/2020/04/29/members-of-the-european-parliament-from-february-2020/ (04.05.2020)

[8] The average age of MEPs is 50 years after Brexit. https://epthinktank.eu/2020/04/29/members-of-the-european-parliament-from-february-2020/ (04.05.2020) The average age in the European Parliament of the eight legislative period was 56 years.

[9] After Brexit https://epthinktank.eu/2020/04/29/members-of-the-european-parliament-from-february-2020/ (04.05.2020)

[10] https://www.europarl.europa.eu/meps/de/search/advanced (04.05.2020)

[11] Thomas Waitz is MEP of the Greens/EFA. He was Member of the European Parliament from November 2017 until May 2019.

[12] Karoline Edtstadler resigned from the EU Parliament on 6 January 2020. She assumed the office of federal minister for EU and constitutional affairs in the Austrian government. Her successor, Christian Sagartz, is only a normal member in the subcommittee of Human Rights.

3] Zotti, Stefan (Juli 2019): Policy Brief: Europäisches Parlament 2019-2024. Präsidium-Ausschüsse-Fraktionen. Politische Analyse. JURKA P.S.A. GmbH Political Strategic Advisors, p. 6.

[14] According to Article 17 paragraph 7 Treaty on European Union, the European Council, acting by a qualified majority, shall propose to the European Parliament a candidate for President of the Commission – taking into account the elections to the European Parliament and after having held the appropriate consultations. This candidate shall be elected by the European Parliament by a majority of its component members. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/en/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A12008M017

[15] Hrbek, Rudolf (2019): Europawahl 2019: neue politische Konstellationen für die Wahlperiode 2019-2014. In: integration 3/2019, p. 182.

[16] Hrbek, Rudolf (2019): Europawahl 2019: neue politische Konstellationen für die Wahlperiode 2019-2014. In: integration 3/2019, p. 183.

[17] Currently, the right of initiative for laws is reserved to the European Commission. Accordingly, legislative processes are initiated always by the Commission. The European Parliament and the Council of the EU have the right of political initiative, which allows both institutions to request the Commission to table new legislative proposals.

The Maastricht Treaty gave Parliament the right of legislative initiative, but it was limited to asking the Commission to put forward a proposal. This right was maintained in the Lisbon Treaty (Article 225 TFEU), and it is spelled out in more detail in an interinstitutional agreement between Parliament and the Commission.

Source: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/factsheets/en/sheet/19/das-europaische-parlament-befugnisse

[18] Speech of Ursula von der Leyen, 16th July 2019, Strasbourg https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/de/SPEECH_19_4230 (02.04.2020) & article Süddeutsche Zeitung https://www.sueddeutsche.de/politik/von-der-leyen-eu-parla-ment-regierungsprogramm-1.4525684 (02.04.2020)

[19] 383 Yes (9 votes more than the necessary majority of 374 votes), 327 no, 22 abstentions https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/de/press-room/20190711IPR56824/parla-ment-wahlt-ursula-von-der-leyen-zur-prasidentin-der-eu-kom-mission (02.04.2020) election of Ursula von der Leyen, 16 July 2019: 383 Yes/327 no/22 abstentions; election of Jean-Claude Juncker, 15 July 2014: 422 yes/250 no/47 abstentions

[20] Von Ondarza, Nicolai (2019): Europawahl 2019: Umbrüche, aber kein Beben im Politischen System der EU. In: Wirtschaftsdienst 2019/6, p. 384.

[21] Hrbek, Rudolf (2019): Europawahl 2019: neue politische Konstellationen für die Wahlperiode 2019-2014. In: integration 3/2019, p. 181.

[22] Vote Watch (January, 2020): European Parliament: cur- rent and future dynamics, S. 19 & Zotti, Stefan (July 2019): Policy Brief: Europäisches Parlament 2019-2024. Präsidium-Aus- schüsse-Fraktionen. Politische Analyse. JURKA P.S.A. GmbH Political Strategic Advisors, p. 7.

[23] Zotti, Stefan (Juli 2019): Policy Brief: Europäisches Parlament 2019-2024. Präsidium-Ausschüsse-Fraktionen. Politische Analyse. JURKA P.S.A. GmbH Political Strategic Advisors

[24] Hrbek, Rudolf (2019): Europawahl 2019: neue politische Konstellationen für die Wahlperiode 2019-2014. In: integration 3/2019, p. 178.

[25] Vote Watch (January, 2020): European Parliament: current and future dynamics, p. 10-11.

[26] Vote Watch (January, 2020): European Parliament: current and future dynamics, p. 10-11.

[27] The EPP membership of the FIDESZ was suspended in March 2019, among other things because of alleged violations of EU fundamental rights as well as several attacks against the then President of the European Commission Jean-Claude Juncker.

[28] Vote Watch (January, 2020): European Parliament: current and future dynamics

[29] Hrbek, Rudolf (2019): Europawahl 2019: neue politische Konstellationen für die Wahlperiode 2019-2014. In: integration 3/2019, p. 178.

[30] Vote Watch (January, 2020): European Parliament: current and future dynamics

[31] The BSP rejected to make the granting of financial assistance from the EU`s Multiannual Financial Framework conditional upon the climate and environmental friendliness of projects.

[32] Vote Watch (January, 2020): European Parliament: current and future dynamics, p. 12-13.

[33] Vote Watch (January, 2020): European Parliament: current and future dynamics, p. 12-13.

[34] Eurobarometer-Umfrage 92.2 des Europäischen Parlaments/Parlameter 2019 (Oktober 2019): Dem Ruf über den Wahltag hinaus folgen. Ein stärkeres Parlament, um die Stimme der Bürger zu hören

[35] Eurobarometer-Umfrage 92.2 des Europäischen Parlaments/Parlameter 2019 (Oktober 2019): Informationsblatt Österreich

[36] ÖGfE-Umfrage (November 2019): ÖsterreicherInnen beurteilen Programm der nächsten EU-Kommission ambivalent https://www.ots.at/presseaussendung/OTS_20191107OTS0044/oegfe-schmidt-oesterreicherinnen-beurteilen-programm-der-naechsten-eu-kommission-ambivalent (08.04.2020)

[37] ÖGfE-Umfrage (November 2019): ÖsterreicherInnen beurteilen Programm der nächsten EU-Kommission ambivalent https://www.ots.at/presseaussendung/OTS_20191107OTS0044/oegfe-schmidt-oesterreicherinnen-beurteilen-programm-der-naechsten-eu-kommission-ambivalent (08.04.2020)

[38] Surveys by telephone, SWS conducted on behalf of ÖGfE, survey 2020: Tel SWS 291, 20-30 April 2020

[39] Surveys by telephone SWS conducted on behalf of ÖGfE, survey 2020: Tel SWS 291, 20-30 April 2020

[40] In May 2018, the European Commission proposed that the EU`s member states´ contribution to the EU budget should be 1,1 percent of the EU-wide gross national income. (https://www.euractiv.de/section/eu-innenpolitik/news/mehrjaehriger-haushalt-meps-ruesten-sich-fuer-kampf-mit-den-eu-staaten/) In February 2020, the President of the European Council, Charles Michel, presented a mediation proposal. According to this proposal, EU member states should pay 1,074 percent of the EU-wide gross national income to the EU budget. (https://www.derstandard.at/story/2000114577642/neuer-kommissionsvorschlag-fuer-eu-budget-bei-1-074-prozent) Nevertheless, the Council of the EU was not able to obtain an agreement until now, since some member states are not ready to pay more than 1 percent of the gross national income to the EU budget.

[41] https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/de/press-room/20200512IPR78912/corona-eu27-braucht-2-billionen-eu-ro-rettungspaket (18.05.2020)

ISSN 2305-2635

The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Austrian Society of European Politics or the organisation for which the authors are working.

Keywords

European Parliament, European elections, Brexit, Austria, opinion, SpitzenkandidatInnen-process

Citation

Edthofer, J., Schmidt, P. (2020). The European Parliament – One year after the European elections. Vienna. ÖGfE Policy Brief, 12a’2020