Policy Recommendations

- The EU should bring more flexibility to the democratisation process. It needs to become participative and regionally anchored.

- Human rights should be at the centre of regional policy formation, even if the benefits of economic exchange or political-military stability are valued highly by policymakers.

- Smaller and specifically targeted projects that favour civil society which can serve as a driver for change may bear more fruit than large packages of financial support bound to EU conditions.

Abstract

The Arab Spring was a major contemporary revolution that extended across the Middle East and North Africa and attracted international attention. This Policy Brief will examine the reaction of the European Union to the Arab Spring and outline how cooperation between the EU, Tunisia and Egypt can be designed to meet regional as well as international expectations and safeguard viable democracies built up on mutual trust. The EU is well-known for promoting democratic values in potential candidate countries and neighbouring states and offers socio-political support if conditions for democratic reform are fulfilled. Comparing Tunisia, a country that has been compliant in meeting these conditions and is on its way to democratic reform, and Egypt, which has fallen back into military rule, the difference in how cooperation with the EU developed is obvious: in Tunisia, the EU advanced at the socio-political level and actively engaged in promoting democracy and human rights; in Egypt, maintenance of the status quo in terms of stable economic relations was pursued. But did the EU’s strategic behaviour meet the specific needs of Tunisia and Egypt? The author analyses the perception and effectiveness of EU support in the aftermath of the Arab Spring and suggests improvements towards a more inclusive and participative conceptualisation of cooperation and support.

****************************

Democratisation after the Arab Spring:

How can the EU effectively support Tunisia and Egypt?

Introduction

“Arab Spring” was the name given to a series of anti-government protests calling for equitable governance, social justice and socio-economic opportunities. The revolution began in late 2010 in Tunisia and quickly spread to Egypt and other North African and Middle Eastern states. Widely reported by international media and depicted as a spark of hope for democracy, it posed challenges and shaped international ties. The EU reacted to this outcry for change with statements, emergency measures and a revised Neighbourhood Policy centred on supporting democratic reform and regaining stability in relations.

Since the Arab Spring, Tunisia has met EU expectations and undergone a democratic transition. Such has not been the case with Egypt.

In the case of the EU, cooperation on a socio-political level – rather than an exclusive focus on economic benefits – depends on a neighbouring state’s willingness to comply with requirements, the central conditions of which include measures for moving towards democracy. Since the Arab Spring, Tunisia has met EU expectations and undergone a democratic transition. Such has not been the case with Egypt, which has been reluctant to implement the EU model of democracy. Instead, Egypt has put its focus on creating economic benefits and implementing large-scale infrastructure projects, choosing to cooperate with Saudi Arabia and other Gulf states. As a result, the EU became less attractive as a partner, and its leverage on Egypt decreased. The post-revolutionary focus centred on maintaining existing economic relations with Egypt. Any safeguarding of democracy or human rights was cast aside because the country’s geopolitical importance and stabilising role in the Saudi-Iranian conflict were at stake. “What now?” becomes a justified question regarding an institution that has so far put great emphasis on “democracy and human rights first”.

How did the EU react to the Arab Spring?

Although the EU reacted in a timely manner, its lack of preparation was apparent. Initial reactions were reflected in public statements of European politicians. Alain Juppé, Nicolas Sarkozy – and later François Hollande, David Cameron, Štefan Füle, Catherine Ashton, Federica Mogherini, and Johannes Hahn, among others – saw a glimpse of hope for political transition; however, they also expressed precaution with regard to security threats.

A programme-based EU response was reflected in a revised Neighbourhood Policy, referred to as the “EU response to the Arab Spring: new package of support for North Africa and the Middle East”. The policy included four new decisions: The SPRING Programme (Support for partnership, reform and inclusive growth), the Special Measure for poorest areas in Tunisia, the Erasmus Mundus Programme, and the Civil Society Facility. Tunisia benefitted most from these new measures. The SPRING Programme, adopted in September 2011 with a budget of EUR 350 million for the period 2011-2013, provided Tunisia with EUR 155 million in funding[1]. Tunisia’s poorest areas also greatly benefitted from the Special Measure, consisting of three components: job creation and social integration, improvement of living conditions, and access to microfinance services[2]. The third decision, foreseeing the involvement of the region in the Erasmus Mundus Programme, ended with a last call in 2016. A Mobility Partnership was signed with Tunisia in 2014 but was declined twice by Egypt. The fourth decision, entitled Civil Society Facility, was envisaged for 2011-2013 – a period too short for building solid partnerships. The short time span was especially a problem for Egypt, where a significant number of Civil Society Organisations are affiliated with the government or led by Islamist actors.

In case of Tunisia specifically, the EU’s socio-political support was also reflected in additional country-specific programmes: the 2012 Privileged Partnership between Tunisia and the EU led to comprehensive support in democratic consolidation, international commitment, socio-economic recovery, structural reforms, trade, joint security solutions, mobility and migration management[3]. Tunisia became the EU’s primary beneficiary in the Southern Neighbourhood, receiving sustained support: in 2014, the EU allocated an overall amount of EUR 169 million to support Tunisia, increasing to EUR 186.8 million in 2015 and to EUR 213.5 million in 2016[4]. Of the EUR 1 billion allocated to Egypt for the period 2007-2013, only EUR 16 million had been paid by 2013, due to Egypt’s non-compliance with agreed-upon conditions[5]. When faced with the instability in Egypt, the EU decided to “freeze” all support and strategic adaptations made in official documents until the country met all necessary conditions.

Which role does democracy play?

The main condition for receiving post-Arab Spring EU support was commitment to a “deep democracy”. “Deep democracy” (conceived in a meeting concerning Tunisia and Egypt in Brussels on 23 February 2011) consists of political reform, elections, institution building, corruption policing, independent judiciary and the general support of civil society[6]. Human rights and democracy were named as key values. When it became clear that the majority of states would not undergo a democratic transition soon, the focus of cooperation went back to stabilisation.

Political conditionality by a so-called “More-for-More” approach, entailing benefits in terms of the “3 Ms” – money, market access, and mobility – was followed through across all four new decisions. In the SPRING programme, progress in democratic reform and institution building were explicitly named as preconditions for increases in support. Tunisia abided by these conditions and received more funding (around 44%) than the other three countries involved (Egypt, Jordan, and Morocco). For these countries and Egypt in particular, the financial incentives were not large enough to motivate compliance.

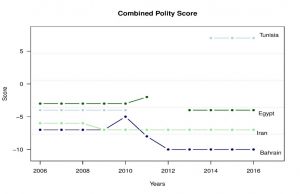

A time series of the Polity IV score measuring regime change shows a backward trajectory in Egyptian democratisation. Based on competitiveness, openness, political participation, and checks on executive authority, Egypt scored higher before the Arab Spring than after, and the country is currently classified as an anocracy.[7]

Figure 1: Combined Polity Score. Source: Center for Systemic Peace (2016)

The EU “supported” democracy instead of actively “promoting” it, and, especially in Egypt, failed.

The EU “supported” democracy instead of actively “promoting” it, and, especially in Egypt, failed. Measures for abolishing human rights violations and corruption should have been implemented across different areas beyond public administration. The concept of a “deep democracy” faded when Tunisia’s transition was considered mostly complete and hope for a transition in Egypt had been abandoned. But, in the face of ongoing protests against increases in prices and cost of living, accepting a transition as either complete or a lost cause means neglecting key democratic values that should be protected and further implemented.

Is EU cooperation effective in meeting country-specific needs?

The EU was perceived as a central actor in Tunisia. Civil society was directly addressed in programmes, which contributed to a positive attitude towards the EU. While new partnerships addressing democratic consolidation, economic growth, job creation and mobility within Tunisia ensure sustained cooperation across different areas, promoting “deep democracy” is no longer at the centre of the post-2015 approach. Unless “deep democracy” is at the core of these programs, corrupt structures might persist within a system that is officially recognized as democratic. Socio-political EU cooperation with Egypt is “on hold”. Egyptian Civil Society Organisations remain deprived of EU support, partly due to their government-affiliations or Islamist leadership. These central actors, including the Muslim Brotherhood and the Hamas, and their concepts of democracy are largely ignored, even though they may also aim at meeting collective needs such as employment and education.[8]

The EU’s decreasing leverage in Egypt

The Egyptian resistance to the EU originates from the following factors: the ineffectiveness of financial incentives, perceived as a drop in the bucket for a large state with high independence and a self-conscious culture; the demand for independent decision-making in thematic fields of cooperation and whether to establish democratic structures in a state shaped by Islamist rule; and an insufficient unity in EU action.[9] On the one hand, EU member states focused on strengthening ties with single countries, putting stronger emphasis on bilateral agreements; on the other hand, the EU itself continued to offer enhanced socio-political support to Tunisia while refraining from political intervention in countries where it was clear that democratic change would not be happening soon. This inconsistency lowered the EU’s normative credibility. It also showed that the EU was not open to new concepts of democracy. In the case of Egypt, at a certain point EU promotion of human rights became secondary. Human rights were used as a condition that needed to be fulfilled to receive enhanced support. Egypt did not satisfactorily fulfil the condition of safeguarding human rights, and the EU did not exert more pressure to ensure that these rights were abided by.

Some European countries like France lauded a “strategic partnership” with Egypt, leaving aside democracy and human rights in favour of economic exchange.

Some European countries like France lauded a “strategic partnership” with Egypt, leaving aside democracy and human rights in favour of economic exchange. However, when it comes to Egypt’s cooperation partners for economic and infrastructure projects, the EU’s role is insignificant compared to other regional players (particularly the Gulf States). On 9 July 2013, after the coup d’état that ousted Morsi, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait and the United Arab Emirates offered Egypt US$12 billion in support (comprised of grants, loans, central bank deposits, and preferential access to oil) with the aim to promote a dissociation from the Muslim Brotherhood. By May 2016, the total volume of pledges by Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and the United Arab Emirates since the coup occurred accounted for US$60 billion, far exceeding the EUR 1 billion of support provided by the EU for 2007-2013. EU funds were further reduced when progress with regard to Egyptian democratisation was not attained. In 2014, funding by the European Neighbourhood Instrument still accounted for EUR 115 million, by 2015 it had decreased to EUR 105 million. While the EU’s regional presence gradually faded, Saudi Arabia’s influence was strengthened through its support of the El-Sisi regime.[10] Due to Egypt’s decreased dependence on the EU combined with the EU’s reluctance to get involved in large-scale projects, the EU lost its leverage. As a consequence, EU efforts to promote democracy were rendered largely ineffective, and will remain so unless more significant action is taken.

Policy Recommendations

The demands of Arab Spring participants – regardless of ideology, education and background – were rooted in social justice and equality based on civil society’s most basic needs. International partners should not impose a model of democratic change derived from their own experience but consider regional needs. The EU, however, does have a certain obligation to safeguard democratic values in terms of human rights, equality and non-discrimination and is expected to express dissent when these values are endangered. It is important to bear in mind that what has been coined the “Arab Spring” is not over, and the core demands are yet to be fulfilled. This is reflected in the ongoing protests in Tunisia as well as Egypt’s reluctance to EU involvement. For the EU to eventually meet the protesters’ ever-present demands and deliver on the promises made in numerous conceptual and programming documents, one approach would be to engage more directly in supporting civil society. It is important that Egypt is not left aside because its definitions and expectations of democracy do not conform to the EU’s concept of democratic reform.

Supporting existing Civil Society Organisations, including those who do not fit the EU ideal (such as organisations led by Muslim Brothers, the Hamas or other significant groupings), as well as establishing local NGOs and engaging in educational, human rights or social health programmes, can be valuable for building a democracy that is social and participative, empowering actors to actively engage in decision-making. Education is key to specify the concept of democracy and training societal actors in building democratic structures. In Tunisia, this would imply developing a certain “democratic self-consciousness” apart from EU requirements. Regarding Egypt, the aim should be to involve actors of different ideologies and provide room for mutual decision-making with a stronger emphasis on human rights.

The EU needs to build trust to gain approval for more socio-political involvement at the local level.

The EU needs to build trust to gain approval for more socio-political involvement at the local level. Trust implies an equal voice in decision-making. This equality cannot be safeguarded when the EU is setting conditions unilaterally. Steps taken towards a clearer conception of a locally desired and participative form of democracy is strongly linked to socio-economic needs, such as tackling present and future unemployment by improving education and mobility. Investing in infrastructure can contribute to both industry creation and boosting economic growth. Economics and politics are not incompatible but rather strongly interrelated, and cooperation between the two is possible. A mutual conception of a social and participative democracy can serve as a basis for a deeper cooperation, resulting in a creation of both socio-political and economic long-term benefits for all.

[1] European Commission (2018). Sustainability Impact Assessments. http://ec.europa.eu/trade/policy/policy-making/analysis/policy-evaluation/sustainability-impactassessments/index_en.htm, retrieved 20/02/2018

[2] European Commission (2011). EU response to the Arab Spring: Special Measure for poorest areas in Tunisia. http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_MEMO-11-642_en.htm?locale=en, retrieved 20/01/2018

[3] European Commission (2017). Relations between the EU and Tunisia. MEMO/17/1263, Factsheet 10/05/17. http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_MEMO-17-1263_en.htm, retrieved 20/02/2018

[4] Bassotti, Giorgio (2017). Did the European Union Light a Beacon of Hope in North Africa? Assessing the Effectiveness of EU Democracy Promotion in Tunisia. EU Diplomacy Paper 6/2017. Bruges: Department of EU International Relations and Diplomacy Studies, p. 26

[5] European Commission (2013). EU-Egypt relations. http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_MEMO-13751_en.htm, retrieved 20/02/2018

[6] Felipe Gómez, Isa (2017). EU Promotion of Deep Democracy in Egypt after the Arab Spring: A missed opportunity? Bilbao: University of Deusto School of Law, p. 6

[7] The Polity IV Score ranges from -10 to +10, with values of -10 to -6 standing for autocracies, -5 to 5 for anocracies – hence, partly autocracies and partly democracies – and 6 to 10 for democracies. The trend graph contains information on special polity conditions such as transition, which is quantified with a Polity Score of -88. These transition values exist for Tunisia and Egypt and were excluded from the visualisation below. According to Polity IV, the transition period for Tunisia had lasted from late 2010 to late 2013, whereas for Egypt it had started in 2011 and lasted until 2013 but was then interrupted. Bahrain and Iran are visualised to draw a comparison to other regimes affected by the revolution to a lesser degree. (Center for Systemic Peace, 2016).

[8] Pace, Michelle (2010). Perceptions from Egypt and Palestine on the EU’s Role and Impact on Democracy Building in the Middle East. Stockholm: International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance 2010. https://www.idea.int/sites/default/files/publications/chapters/the-role-of-the-european-union-in-democracy-building/eu-democracy-building-discussion-paper-19.pdf, retrieved 28/02/2018

[9] These conclusions are based on interviews with experts from the World Bank, the Austrian Institute for International Affairs, the European Parliament, and the Austrian Federal Ministry for Europe, Integration and Foreign Affairs.

[10] Felipe Gómez, Isa (2017). EU Promotion of Deep Democracy in Egypt after the Arab Spring: A missed opportunity? Bilbao: University of Deusto School of Law, p. 20-22

- Czypionka, T., Schnabl, A., Lappöhn, S., Plank, K., Reiss, M., Weyerstraß, K., Wimmer, L., Zenz, H. (2020), Abschätzung der wirtschaftlichen Folgen des Ausbruchs des neuartigen Coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) – 5. Mai 2020, IHS Policy Brief Nr. 13, 24. https://irihs.ihs.ac.at/id/eprint/5314/

- Grossmann, B., Schuster, P. (2017), Langzeitpflege in Österreich: Determinanten der staatlichen Kostenentwicklung, Studie im Auftrag des Fiskalrates, Vienna. https://www.fiskalrat.at/Publikationen/Sonstige.html

- EU hat die Krise unterschätzt, Interview mit Karoline Edtstadtler, Salzburger Nachrichten, 20. Mai 2020, 9.

- Marzi, L.-M., Der juristische Notfallkoffer – neue Wege zur Begrenzung zur Schadensbekämpfung im Krankenhaus, Zak 8/2009, 146-148.

- Marzi, L.-M., 10 Jahre „Juristischer Notfallkoffer“ im Allgemeinen Krankenhaus Wien. Erfahrungen und Veränderungen in der Schadensabwicklung, Zak 17/2017, 327-330.

- Marzi, L.-M., Risk management and healthcare safety: Ten years of experience at the Vienna General Hospital, Journal of Patient Safety and Risk Management, 2018, Vol. 23(6), 265–268.

- Marzi, L.-M., The Legal Emergency Kit, Official Journal of the European Association of Hospital Manager, 2011, Vol. 23, Issue 1, 2011, 12-14.

ISSN 2305-2635

The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Austrian Society of European Politics or the organisation for which the author works.

Citation

Wurm, L. (2018): Democratisation after the Arab Spring: How can the EU effectively support Tunisia and Egypt? Vienna. ÖGfE Policy Brief, 19’2018