What might be the implications for the EU?

Policy Recommendations

- The Paris Agreement is broadly seen as a strong impulse for global climate policy. The challenge is to transfer it into “best effort” policy and economy.

- The outcome of the Paris Climate Conference will be another Litmus test for the EU if its Member States are still committed to a cooperative and constructive commitment for solving global policy challenges.

- The EU should aim at regaining its credibility in the brief history of global climate change policy, for example by a fundamental reform of the Emissions Trading System or the introduction of effective carbon taxes.

Abstract

In retrospect the most relevant outcome of the Paris Climate Conference might be that there is an agreement at all. The subtleties of the Paris Agreement text concern not only the overall design of voluntary national commitments, the implications of temperature limits of 2.0°C and 1.5°C, and the credibility of the financial mechanisms, but above all the vulnerability with respect to the Nationally Determined Contributions and the consequential national policy changes because of the weak or missing internationally legal binding. Nevertheless the Paris Climate Conference is broadly assessed as a breakthrough in international climate policy, mainly because of the participation of the biggest greenhouse gas emitters as China and the United States, or countries, which are building their wealth on fossil energy as the oil producing states. The Paris Agreement can be seen as alarm signal to avoid lock-in investment in long-lived fossil infrastructure and therefore will require major policy changes also for the EU. The Nationally Determined Contribution of the EU for 2030 is at the border between moderate and poor and reflects major policy failures: the flaws in the design of the EU Emissions Trading System that led to its current breakdown; the vain endeavor to achieve minimal tax standards targeted to energy efficiency and CO2; the missed opportunities, e.g. in cohesion policy or the Juncker plan, to provide incentives for restructuring to a low-carbon economy; finally the EU Energy Union strategy, which reflects an outdated mindset for dealing with energy. Thus the outcome of the Paris Climate Conference will be another Litmus test for the EU if its Member States are still committed to a cooperative and constructive commitment for solving global policy challenges.

****************************

Deciphering the Paris Agreement on Climate Policy: What might be the implications for the EU?

The outcome of the Paris Climate Conference in a nutshell

In retrospect the most relevant outcome of the Paris Climate Conference might be that there is an agreement at all. The fragility of the negotiations is reflected in the sensibility to wording in the run-up to the final plenary session in Paris, which could not start because the United States insisted that a “shall” in the text had to be replaced by a “should”.

For persons not familiar with the negotiating procedures the agreement text is rather difficult to decipher. The subtleties concern not only the overall design of voluntary national commitments, the implications of temperature limits of 2.0°C and 1.5°C, and the credibility of the financial mechanisms, but above all the vulnerability with respect to the Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) and the consequential national policy changes because of the weak or missing internationally legal binding. Ultimately the ambition and effectiveness of these NDCs will become visible in the five year review cycles and the accompanying emissions data.

It is the transfer into national policy that needs to be framed in a changed mindset by understanding that the temperature target of Paris needs a deep transformation process.

Nevertheless the Paris Climate Conference is broadly assessed as a breakthrough in international climate policy, mainly because of the participation of the biggest greenhouse gas emitters as China and the Unites States, or countries which are building their wealth on fossil energy as the oil producing states. The common global understanding that climate change is a real threat to human societies, which calls for action to keep temperature increase well below 2°C compared to pre-industrial levels, can be interpreted as progress in climate negotiations although the hard work still lies ahead. The Paris Agreement can be seen as alarm signal for investors to avoid lock-in investment in long-lived fossil infrastructure. If the Paris Agreement will create more than temporary media hype will be tested soon in the ratification process that ends in April 2016 and the echoes of national actions, not only after 2020 when the agreement will come into force, but already in the years up to 2020. It is the transfer into national policy that needs to be framed in a changed mindset by understanding that the temperature target of Paris needs a deep transformation process[1].

The Paris Agreement and the accompanying COP Decisions

The key outcomes of what is known as COP 21 is a document called COP Decisions and as an annex the Paris Agreement. Both the Decisions and the Agreement extend the new architecture for global climate policy which had become first visible at the failed Copenhagen Climate Conference in 2009. The main pillars of the new architecture are:

- There is an explicit goal to keep global warming below 2° C and even a reference to a 1.5° C limit.

- All countries have to contribute to achieve this goal although there is recognition on the special needs of developing countries “including the principle of equity and common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities, in the light of different national circumstances”.

- All commitments are voluntary and therefore non-binding, relying on transparency rather than legal enforcement.

- This holds in particular for the system of national pledges for emissions reductions which are referred to as Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs).

- Transparency and clarity of the NDCs is stressed as well as a stock-take on actions every five years. This should allow periodic assessment of the NDCs as well as monitoring progress on the implementation of the Paris Agreement.

- A pledge to mobilise annually 100 billion US$ climate financing from public and private sources by 2020.

- Net zero emissions are to be achieved in the second half of the century.

To what extent these main elements are legally binding requires some careful deciphering of the Decisions and the Agreement. In particular the United States insisted that the Agreement contains less binding language, thus enabling the U.S. President to accept the Agreement without Senate or Congressional approval. Remarkably neither the actual NDCs nor the envisaged volume for climate financing is part of the binding Agreement.

The challenges of the Paris Agreement for the EU

The NDC of the EU is laid out in the climate and energy framework of the EU for the period 2020 to 2030 which basically follows the structure of the 20-20-20 climate and energy package. It builds on three pillars, namely a greenhouse gas (GHG) target that is split up between the sectors regulated by the EU Emission Trading System (ETS) and an emission reduction target for the non-ETS sectors, a target for the share of renewables in energy consumption and an improvement of energy efficiency compared to a baseline development. For 2030 the GHG emissions reduction target is 40 percent compared to 1990. Both the renewables and the energy efficiency target are set at 27 percent.

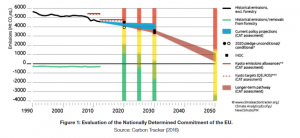

Carbon Tracker evaluated the ambition of the submitted NDCs. The results for the EU in Figure 1 indicate the pronounced decline of EU emissions. This decline, however, reflects mainly the ongoing economic crisis and energy efficiency improvements in the new Member States. The vertical bars for 2020, 2025, 2030 and 2050 indicate by the colors red, yellow and green the ambition levels poor, moderate and high. Thus the NDC of the EU for 2030 is at the border between moderate and poor. Obviously the EU would need a much more ambitious reduction path in order to achieve the desired decarbonisation by 2050.

Figure 1: Evaluation of the Nationally Determined Commitment of the EU.

Source: Carbon Tracker (2016)

The message in Figure 1 is obvious: The EU has lost a lot of credibility in the brief history of global climate change policy, which started with signing the UNFCCC[2] document in 1992 and as a first milestone in 1997 the adoption and later ratification of the Kyoto Protocol. We exemplify this erosion of credibility by referring to a few currently debated policy issues.

EU policy failures: The breakdown of the EU Emissions Trading System (EU ETS)

Directive 2003/87/EC of 13 October 2003 establishing a scheme for greenhouse gas emission allowance trading within the EU was at that time an outstanding and courageous policy decision that currently involves emissions from more than 14,000 installations.

The reasons for the breakdown of the EU ETS are obvious design flaws, which reflect basic controversies over EU policy governance.

The EU ETS started in 2005. Soon together with the price for emissions allowances also the built-up high expectations collapsed. Currently the price for emissions allowances would add not more than one Eurocent to a liter of fuel. The reasons for this breakdown of the EU ETS are obvious design flaws which reflect basic controversies over EU policy governance. One design flaw was up to 2012 the strong influence of Member States on issuing free allowances. This should safeguard domestic industry from relocation of production and investments under the heading of carbon leakage. A new governance scheme started in 2013 without being able to cope with the huge surpluses on the carbon market which amount now to way beyond one year’s emissions. The Commission has put forward reform proposals of the EU ETS in July 2015. There is a strong consensus, however, that these envisaged reform steps will not suffice to provide a credible price signal that gives guidelines for the transition to a low-carbon economy.

EU policy failures: Missing an EU wide CO2 price signal for non-EU ETS

Directive 2003/96/EC of 27 October 2003 restructuring the Community framework for the taxation of energy products and electricity sets minimum tax rates for energy products, leaving it to the competence of Member States to set higher tax rates according to national preferences. The energy directive was adopted before Member States agreed on the climate and energy package and thus does not reflect the climate and energy policy targets. In response to that the Commission proposed in 2011 an amendment which had shown some features that could have been supportive to the Paris agreement:

- Minimum tax rates in Directive 2003/96 differ strongly between energy sources and energy products and do not account for CO2 intensity of energy products. The proposed amendment distinguished between a CO2-component and the energy content of an energy source.

- The CO2 tax component was proposed to be levied on sectors not regulated by the EU ETS in order to extend the carbon price signal to the Non-ETS sectors.

- Amending Directive 2003/96 thus should ensure that energy taxation avoids overlap with and would be in line with other EU legislation relating to GHG emissions and energy use.

A unanimous decision by all Member States could not be reached and the proposal was finally withdrawn in early 2015, leaving a patchwork of national approaches when it comes to pricing CO2, where the majority of Member States refrain from taxing CO2 (exemptions are e.g. Ireland or Sweden).

Up to now, Member States also failed to agree, in addition or alternatively to minimum tax rates, on own EU taxes which on the EU level could be enforced much more effectively compared to unilateral implementation – e.g. an EU-wide kerosene tax or flight ticket tax.[3] The revenues of own EU taxes could replace a part of EU own resources to finance EU expenditures, which currently do not contribute at all to decarbonisation.

EU policy failures: An outdated mindset for dealing with energy

Another indicator that the EU needs a better understanding of the links between energy and climate and the opportunities of a radical transformation is the EU Energy Union strategy. With its five dimensions (supply security, fully-integrated energy market, energy efficiency, emission reduction, research and innovation) only seemingly the big challenges of our energy systems are addressed. It follows a view of the energy system that is focused on energy flows but not at the ultimately relevant purpose of providing energy services, as thermal services of a building, mechanical services for production and mobility, or specific electric services of lighting and electronics[4].

EU policy failures: Unsustainable structures of the EU budget

The EU budget hardly contributes to a decarbonisation strategy. Common agricultural policy predominantly supports environmentally unsustainable production structures and is only slowly reoriented towards sustainable agricultural production and rural development. Cohesion policy is hardly coupled with climate targets. The share of research expenditures is rising only slowly: It has reached over ten per cent of overall EU expenditures; however, less than one tenth of the funds reserved for the current research framework programme Horizon 2020 is dedicated to research on climate change.

EU policy failures: The Juncker plan (EFSI) as a missed opportunity

According to EFSI guidelines it should support primarily (public as well as private) investment projects in the fields of transport and communication infrastructure, research and development, education and SME. Thus EFSI does not have a special focus on projects supporting a socio-ecological transition, as investment in „green“ research, renewables, or energy efficiency. Moreover the Fiscal Pact leaves too little room for sustainability-promoting public investment, as the so-called flexibility clause is formulated rather restrictively. This limits the options to enforce public investment through EFSI, which has been reduced markedly since the onset of the current crisis.

Will the Paris Agreement survive the political storms ahead?

“Everything is done but nothing is done” warns Laurence Tubiana, the French ambassador for international climate negotiations with the Paris Climate Change Conference who deserves high praise for forging the Paris outcome.

[zitat inhalt=”Despite the political momentum that was built-up to Paris and despite the presence of 150 heads of state, the political attention span of the Paris experience is short.”]

Let’s face it: Despite the political momentum that was built up to Paris and despite the presence of 150 heads of state, the political attention span of the Paris experience is short. Upcoming political priorities are the ongoing global economic slow-down, the threat of another financial crisis, and unpredictable developments spreading from China to the rest of the world. The dramatic fall of prices for fossil energy, in particular crude oil, adds new barriers to shifting to a low-carbon economy. A first test of the validity of the Paris Agreement will be the official signing by world leaders to be expected in April. The next test will be ratification, where President Obama is expected to take the lead through his executive authority, thus bypassing Congress. His political opponents have made it very clear that they will do everything to reverse Obama’s courageous climate policy.

And then there is the EU. Recent episodes in the context of climate policy are not encouraging. Two weeks after the Paris Climate Conference Poland went to the European Court of Justice, fighting a tightening of the market for emissions allowances. The new Polish government even announced that they will for the time being block the remaining legal procedures needed for the hardly known second commitment period of the still existing Kyoto Protocol.

The outcome of the Paris Climate Conference will be another Litmus test for the EU if its Member States are still committed to a cooperative and constructive commitment for solving global policy challenges.

To put it bluntly: The outcome of the Paris Climate Conference will be another Litmus test for the EU if its Member States are still committed to a cooperative and constructive commitment for solving global policy challenges. Climate policy definitely belongs to this agenda.

[1] This especially requires a fundamentally new understanding of our energy systems that focuses on adequate and affordable energy services and not the availability of cheap energy.

[2] United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change.

[3] Such options are currently elaborated in the H2020 project „FairTax“ (www.fair-tax.eu).

[4] Recent research projects in Austria as EnergyTransition, ClimTrans, or WWWforEurope strongly emphasise this inversion of the policy mindset that requires also a retooling of the policy instruments. The most recent lesson is obtained from the decline of energy prices: consumers are much better off from a highly energy-efficient infrastructure – as buildings, integrated zoning regulation and related low-transport needs – than from cheap fuel prices.

- Climate Action Tracker (2016), Tracking INDCs, http://climateactiontracker.org/indcs.html.

- European Commission, Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council and the European Economic and Social Committee. A policy framework for climate and energy in the period from 2020 to 2030, COM(2014)015. Brussels, 2014.

- European Commission, Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council and the European Economic and Social Committee on Smarter energy taxation for the EU: proposal for a revision of the Energy Taxation Directive 2003 Brussels, 2011.

- European Commission, Directive 2009/29/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 April 2009 amending Directive 2003/87/EC so as to improve and extend the greenhouse gas emission allowance trading scheme of the Community, Brussels, 2009a.

- European Commission, Decision No 406/2009/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 April 2009 on the effort of Member States to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions to meet the Community’s greenhouse gas emission reduction commitments up to 2020 (“Effort Sharing Decision”). Brussels, 2009b.

- European Commission, Directive 2009/28/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 April 2009 on the promotion of the use of energy from renewable sources and amending and subsequently repealing Directives 2001/77/EC and 2003/30/EC (“Renewable energy Directive”), Brussels, 2009c.

- European Commission, Directive 2009/31/EC – Directive on the geological storage of carbon dioxide, Brussels, 2009d.

- European Commission, Directive 2003/96/EC on restructuring the Community framework for the taxation of energy products and electricity; Brussels, 2003.

- Schleicher S., Köppl, A., Policy Brief: Die Klimakonferenz 2015 in Paris. Neue Markierungen für die Klimapolitik?, Wien, 2015.

- Schleicher, S., Marcu, A., Köppl, A., Schneider, J., Elkerbout, M., Türk, A., Zeitlberger, A., Scanning the Options for a Structural Reform of the EU Emissions Trading System. CEPS Special Report, Brussels 2015. http://www.ceps.eu/publications/scanning-options-structural-reform-euemissions-trading-system.

- UNFCCC, Conference of the Parties Adoption of the Paris Agreement, Paris, 2015.

ISSN 2305-2635

The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Austrian Society of European Politics or the organisation for which the authors work.

Keywords

climate policy, climate change, emissions trading system, decarbonisation

Citation

Schleicher, S., Köppl, A., Schratzenstaller, M. (2016). Deciphering the Paris Agreement on Climate Policy: What might be the implications for the EU? Vienna. ÖGfE Policy Brief, 09’2016

Note

In combination with this Policy Brief an op-ed has been published in German in the newspaper “Der Standard” and on EurActiv.de.