Policy Recommendations

- The EU is committing large amounts of money to combat the COVID-19 crisis, also at international level. Yet, one lesson it has to learn is to effectively improve coordination in the field of health related issues and professionalize its public relations.

- European leaders must continue to take strong actions in favour of our neighbouring partners. In today’s situation, in which COVID-19 wreaks havoc in the Union’s fragile eastern and southern surroundings, and in which multilateralism is at a serious risk to further deteriorate exactly when it is most needed, hibernation is not an option for Europe’s external engagement efforts. The forthcoming EU Eastern Partnership summit in June and the EU-African Union summit in October 2020 should be used by EU leaders to publicly confirm these aspirations.

- The EU has reacted quickly at the science front, but now it needs to secure its financial contribution to the European and Developing Countries Clinical Trials Partnership under Horizon Europe, the next European Framework Programme for Research and Innovation.

Abstract

With the worldwide outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, we are experiencing intense competition between global players as to who can best contain the crisis and who is a reliable international partner in the global fight against the coronavirus and the economic and social consequences it causes. The EU appears to have been disqualified in that game of rivalry right from the start due to its lack of internal coordination and solidarity. After a moment of shock, however, the EU now seems to have gathered steam in terms of globally engaging against the coronavirus crisis and could outpace its main competitors such as China and Russia. Now, more than two months after the crisis started to severely hit also the EU with Italy as the first member state in its epicentre, there is accumulating evidence to prove this fact: Increasing investments in research and development, an active science diplomacy and fast, but also sustainable reactions in the field of development cooperation. However, existing resources in development cooperation do not suffice to overcome the full scale of this global crisis, which demands more than health supply and economic aid. More farsighted approaches, that forward the long-term goals for social, ecological and ecomic recovery after the crisis, and an improved information policy with stronger public relations will be necessary for the EU so that it can reliably maintain its position as the most important and partnership-oriented partner for Africa and its Eastern neighbourhood.

****************************

The EU’s global response to the COVID-19 crisis with a focus on the Eastern Neighbourhood and Africa

1. A global competition for a global crisis narrative

One of the effects of the COVID-19 crisis is a seemingly bizarre competition between the major global players around the narrative of who handles the crisis best and who is a reliable global partner. One might think that the EU disqualified itself from this competition right from the start due to the lack of coordination and solidarity within Europe. But there are glimmers of hope, which include scientific-technical cooperation, science diplomacy and international cooperation. China has long looked like the winner of the competition of who is a reliable global partner in supporting the containment of the crisis, but is increasingly criticised for its perceived lack of transparency (at least as regards the immediate outbreak) and its overly emphatic narrative as the saver of the world. The United States is practicing the role as a global asperser. After initially positive reports of rapid foreign aid delivered, Russia has now primarily to deal with itself.

In the end, three main factors will determine the outcome of the competition:

- Who best provided emergency aid?

- Who will best assist with recovery measures?

- Who will be the first to bring the required medicines and the longed-for vaccine onto the market – and under what conditions?

The EU’s first response to the COVID-19 crisis was lacking a joint approach creating a devastating public image of the Union.

The EU, which initially had very bad cards because it wasted the emergency aid narrative, operates currently much more successfully with regard to the other two factors of “recovery aid” and “health research”. In particular, the narrative of making a vaccine against COVID-19 available to everyone globally at low cost and not just considering it a huge product market was helpful.

The EU’s first response to the COVID-19 crisis was lacking a joint approach, which created a devastating public image of a Union lacking solidarity[1]. Health is primarily a matter for the EU member states and they failed to coordinate. Freezes in delivery of medical supplies within the EU were imposed, Italy’s cry for help was ignored for too long, and the borders were closed without sufficient consultation processes. The situation even aggravated by the fact that the European Commission’s competence in relation to public health is marginal and the little that is available has acted unfortunate.[2]

2. Global cooperation in research to tackle the virus –

where science and foreign policy meet

However, the situation is different with regard to research policy. The European Commission (EC) reacted very quickly and much faster than the EU member states. Already on 30 January 2020, the EC launched a request for expressions of interest for clinical and public health response to the COVID-19 epidemic with a budget of €48.2 million. Deadline for this ‘EU Coronavirus emergency funding’ was already on 12 February 2020. Open data procedures were compulsory. 18 projects were then funded as of March 2020. These projects involve 151 research teams from across the EU and beyond, including Albania, China, Ivory Coast, Nepal, North Macedonia, and Switzerland.

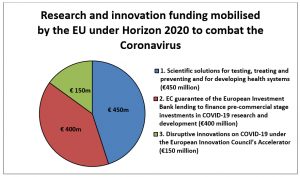

Meanwhile, the EU has already committed more than €380 million to research and innovation efforts to develop vaccines, new treatments, diagnostic tests and medical systems to prevent the virus from spreading.[3] This sum was accumulated through the above mentioned ‘EU Coronavirus emergency funding’, funding provided by the European Innovation Council, and funding coming from initiatives such as the ERAvsCORONA Action Plan[4], the ‘Innovative Medicines Initiative’[5], the EU-COVID-19 Data Platform[6], the EUvsVIRUS Hackathon[7] and others.

As regards Africa, the European and Developing Countries Clinical Trials Partnership (EDCTP) invested more than €600 million since 2003. It was established to support the development of new or improved drugs and to develop capacities in Africa. At global level, EDCTP is often perceived as a lighthouse project. It intends to finance projects with a budget of up to €28 million from Horizon 2020 plus additional finances from its member states to enhance coronavirus pandemic preparedness and point-of-care diagnostics in sub-Saharan Africa. This Horizon 2020 investment is in line with the EU’s commitment to step up scientific cooperation with the African Union as set out in the Commission’s comprehensive Africa Strategy adopted on 9 March 2020.

On 4 May 2020, the EU finally joined forces with global partners to kick-start a pledging effort – the “Coronavirus Global Response Initiative”. This event was certainly a trigger that allowed the EU to position itself again as a global player in regaining the narrative in the struggle against COVID-19. On the first day, €7.4 billion were raised to set global research cooperation in motion with a focus on diagnosis, treatment and vaccine development. The EU pledged to mobilise €1 billion under its current framework programme for research and innovation and €400 million in guarantees on loans [8]. Norway promised $1 billion. Japan pledged more than $800 million, Germany, France and Italy each promised around €500 million, while the UK pledged just over €440 million[9]. Austria’s pledge, however, was comparatively humble (€31 million). The USA and Russia did not even participate. While the actual materialisation of such commitments into tangible actions is fraught with uncertainty, the event was a strong signal for multilateralism pushed by a strong EU claiming its worldwide top position in the field of research and innovation. Most of the pledges by countries, however, are not earmarked for international R&D cooperation but benefit national R&D activities.

Figure 1: Research and innovation funding mobilised by the EU under Horizon 2020 to tackle the coronavirus as of May 2020 (Source: European Commission, own visualisation)

Science diplomacy as a means of supporting geopolitical and foreign policy goals is nothing new to the EU.

Science diplomacy as a means of supporting geopolitical and foreign policy goals is nothing new to the EU. The EU’s external Research and Development (R&D) policy was carried out as a ‘soft power’ policy long before the term ‘science diplomacy’ became fancy. International research cooperation with developing and neighbouring countries was first included in the 3rd European Framework Programme for Research, Technology and Development (FP3) (1991-1994). R&D cooperation with (post-)industrialised countries was more contingent but received more importance during the last ten years, after the EU enlargement policy focusing on the Central European countries was successfully attained.

The EU’s foreign R&D policy is characterised by an asymmetric order, an open and variable spatial structure and the integration through regulations, consensus and voluntary cooperation. Through its research framework programmes the EU produces “club goods”, which are made accessible to non-EU countries under specific conditions. The EU’s enlargement towards Central European countries in 2004 for instance was based on a process of gradual commitments and integration with asymmetric membership formats and membership rights.

The current EU external periphery in the field of R&D can be further differentiated in

- non-EU countries associated to Horizon 2020 with an integration perspective (e.g. Western Balkan countries and Turkey),

- non-EU countries associated to Horizon 2020 (e.g. Tunisia, Israel, Ukraine, Georgia, or Armenia),

- European Neighbourhood Countries without association to Horizon 2020,

- other countries automatically funded by Horizon 2020,

- and countries that can participate in Horizon 2020 projects on their own expense.

3. The EU’s engagement to counter the Coronavirus crisis in the Eastern Neighbourhood and Africa

On 8 April, the European Commission and the High Representative announced that the EU will contribute more than €15.6 billion from existing external action resources to strengthen partner countries’ health, water and sanitation systems and their research and preparedness capacities to deal with the pandemic, as well as to mitigate the socioeconomic impact caused by the current crisis. This European response reshuffles resources from the EU, its member states and financial institutions, in particular the European Investment Bank (EIB) and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) (so called ‘Team Europe’ approach) to fight the COVID-19 crisis in the partner countries. Most of this budget is earmarked for Africa and the neighbouring countries in the East and the South including the Western Balkans.

On 27 May, a press release confirmed the EU’s commitment in leading international multi-lateral efforts towards a truly global recovery, notably though joint coordination with the United Nations, the G20 and G7, the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank or the International Labour Organisation. The EU stressed that it will continue to work particularly closely with its immediate neighbourhood in the East and South and its partners in Africa.[10]

3.1 The Eastern Neighbourhood – seeking for long-term stability

Through the Eastern Partnership (EaP), which marked its 10th anniversary last year, the EU is strengthening its ties with Belarus, Ukraine, Moldova, Georgia, Armenia and Azerbaijan. Since 2017, the EaP was guided by four main policy areas for cooperation, which, at the same time, provided a common ground for defining 20 specific objectives to be reached by the year 2020. These so called “20 Deliverables for 2020” targeted the policy areas of economy, governance, connectivity and society. In 2019, the European Commission carried out a broad and inclusive consultation to define the future policy objectives under the EaP. The results of this consultation were published on March 18 and although the corona crisis had started to impact both on EU and EaP countries already, nobody at that time knew that the new catchphrase ‘reinforcing resilience’ for the EU EaP policy framework beyond 2020 would become so topical.

The assumption that the EU’s partner countries in the southern and eastern neighbourhood must continue pursuing peace and stability in order to guarantee the EU’s security in the long term holds true in EU foreign action until today.

Due to poorly equipped health systems and weak social programmes, our six eastern neighbours are in a particular vulnerable position for corona crisis related effects. Strained financial households won’t be able to set into place a full portfolio of financial support mechanisms to cushion the economic downturn caused by the lockdowns. As rich neighbour the worst the EU could do is leaving the countries now alone with the crisis. Miriam Kosmehl, Senior Expert Eastern Europe and European Neighbourhood at the Bertelsmann-Stiftung, adds that “showing solidarity here is not only essential for good neighborliness and cohesion, it is also farsighted – since only healthy nations can create a stable ‘ring of friends’ around the EU”[11]. The term ‘ring of friends’ goes back to former EC president Romano Prodi, who introduced it in 2002 as part of a new geo-political strategy for the EU’s role in its immediate neighbourhood and in the world[12]. The key term within that strategy was ‘proximity’, and it accounted for the EU’s shift towards a more deepened and inclusive neighbourhood policy. It was believed that only if the EU’s immediate neighbours in the South and the East (spanning from North Africa to the Middle East and Eastern Europe) will be transforming to democratic countries with political systems that are rule of law-based, and that promote peace and stability, also the EU’s security can be guaranteed on the long term. This assumption holds true until today and continuous to play a critical role in the EU’s deliberations on the neighbourhood (albeit now rather in the background as a widely agreed common sense between the key actors).

It was March 30 when Brussels officially announced the first large support package of almost €1 billion to the EaP countries to combat the virus and to cope with short- and long-term socio-economic effects of the crisis. Nevertheless and despite the substantial finances released, the EU also has to win back the mentioned lost narrative on being the most reliable partner for the region, which has been primarily shaped by Chinese and Russian influence during the first weeks of European feverish passivity.

3.2 Africa – building international coalitions to maximise help

Regarding the economic situation caused by the COVID-19 crisis in Africa, some first observations could already been made.

Firstly, the spread of the virus in Africa is for the time being lower than elsewhere, but scientists fear that this is caused by a low number of tests and/or will come temporarily delayed but probably with a huge impact aggravated by the poor healthcare situation. This assessment is still quite speculative.

Secondly, the paralysis of world trade and international communication and transport due to the crisis affects also Africa through collapsing international trade and global supply chains, falling remittances, sharp reversals of capital flows, currency depreciation and severe problems in meeting foreign currency payment obligations[13].

Thirdly, Africa’s economy is coined by a high share of informal economic activity. This informal sector is directly affected by any lockdown. Millions of people who live from a day-to-day business are the first ones suffering. They are deprived of incomes, causing huge declines in consumption.

Fourthly, Africa, traditionally, does not have a lot of instruments needed for an economic stimulus package in times of an economic crisis. There is no safety net for African banks as we saw it emerging on the European continent after the 2008 financial crisis. African banks are only at the very beginning to organise themselves in order to practice what others do in terms of monetary policies in times of crisis, says Professor Carlos Lopes in an online conversation with Chatham House on April 9[14].

The deadly combination of collapses in both demand and supply is why this time is truly different and has to be dealt with differently. (Jayati Gosh)

On April 11, the EU launched the ‘Team Europe’ to support countries around the world in their fight against the coronavirus crisis with an overall financial support of more than €20 billion[15]. From this overall amount, and what is secured until today’s date, at least €3.25 billion are channelled to Africa, €3.07 billion are promised to the whole neighbourhood (including the southern and eastern partners as well as the Western Balkan Countries and Turkey) and more than €2 billion are earmarked for other world regions such as Latin America, the Pacific region and the Caribbean. Another €1.42 billion in guarantees from the European Fund for Sustainable Development also benefits African countries and the whole neighbourhood.[16] More so, latest discussions indicate that the EU is willing to do even more. A far ranging debt relief mechanism for African countries that currently grapple most with the coronavirus crisis is currently discussed[17].

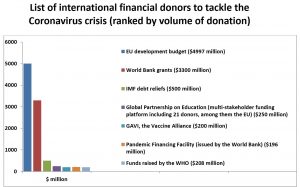

Comparing the financial support provided to single countries so far, the EU is, in fact, the biggest international financial donor.

According to reports from ‘The New Humanitarian’, an independent non-profit news organisation founded by the United Nations in 1995, the EU’s international financial donations as a response to the shock of COVID-19 (classified as development donations and excluding direct humanitarian aid) sum up to around $4.1 billion as of April 28[18]. This makes the EU the world’s largest financial contributor in the current crisis, spearheading a list of other big funders such as the World Bank (WB) and the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

Figure 2: Ranking of international donors on the basis of financial donations provided as of April 28, 2020 (excluding direct humanitarian aid) (Source: FTS – Financial Tracking Service provided by OCHA, own visualisation)

4. Harsh future fiscal dependencies – a looming scenario

Both regions, the Eastern Neighbourhood and Africa, are forced into massive future dependencies from International Financial Institutions (IFIs) as a result of the current crisis. The International Monetary Fund, the World Bank and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development are prospecting large amounts of loans to the regions answering to the current economic urgency (EBRD is mainly involved in relieving the EaP countries, the contributions to Africa are more significant from IMF and World Bank). The IMF is particularly active in channelling billions of Euros to Africa[19]. By early April, eighty-five countries worldwide had approached the IMF for emergency assistance because of severe problems in meeting foreign currency payment obligations, and that number is likely to rise.

A Keynesian response to the crisis with increased government expenditures to stimulate the suffering economy can only be afforded by the richer countries.

The large financial aid distributed now will lead into major negotiations for macro-financial loans in the direct aftermath of the crisis, as governments try to manage a return to economic normality. The case of Greece, which has experienced the worst economic downfall in its national history as a consequence of the 2008 financial crisis, is still very present. As a condition for receiving financial aid, a series of sharp austerity measures had to be implemented by the Greek government resulting in a significant downscaling of public services. This future scenario of a far-reaching macro-financial dependency for the years to come is definitely also looming in the case of the Eastern Neighbourhood countries and Africa. A Keynesian response to the crisis with increased government expenditures to stimulate the suffering economy can only be afforded by the richer countries. The developing countries in Europe’s east and in Africa will hardly be able to do this. Thus, international donors, including the EU, must continue providing even more conditionality-free loans and the industrial capacity in developing countries needs to boot up. This also implies that developing countries are allowed to manufacture vaccines and medicines to combat the COVID-19 pandemic, which is likely to contradict the patent rights of Western companies, and which brings us back to the question of international research cooperation.

5. Thinking ahead – cooperation after COVID-19

As many scholars rightfully point out, the COVID-19 crisis is not only a destructive, but also very inventive force. Our current way of living is under complete upheaval, and global cooperation is put under a severe stress test with dimensions unknown before. Productive, far-sighted and balanced decisions as well as visions are needed more than ever. It is an environment favourable to multilateralism and the power of international cooperation, also if there are opposing views, which have always and will always exist. Withdrawing from international agreements or quitting with practices established in international organisations as a proof for real leadership in crisis times will cause harm and may backfire. In this line, the US President is well advised to revoke his decision to cut US funding to the World Health Organisation (WHO) in the midst of this unprecedented global health crisis[20].

The EU, on the other hand, can tap into this emerging potential for global leadership. Concerning the further provision of medical and financial assistance to Africa and the Eastern Partnership countries, it should intensify its cooperation with the WHO (for medical aid and surveillance), the World Bank, IMF, EBRD, and the EIB (for financial support). Consequently, strengthened multi-lateral global cooperation also requires the EU to contribute more financial support towards the WHO and the Global Coalition of Epidemic Preparedness Innovation[21] ) (to which the EU provided €20 million so far), and to possibly take a lead in the coordination of international initiatives under the Global Research Collaboration for Infectious Diseases Preparedness (GloPID-R)[22].

Conclusions and recommendations

- The relatively slowly coordinated response of the EU and glaringly unprofessional public relations have contributed to the picture of a weak Europe during the first phase of the COVID-19 crisis. The resulting damage can be hardly compensated by the large amount of money, which the EU is committing to combat the crisis, also at international level. It is cheaper and, in the short term, also more effective to have a positive impact on public discourses quickly. This requires faster coordination in the field of health related issues and better public relations to improve the appearance of the EU.

- Since the crisis drastically affects economic structures and social conditions, amplifies old and forms new lines of inequality, the quick reshuffling of existing budgets for international cooperation is laudable, but will not suffice. Fresh money needs to be provided in time including new loans for international partner countries without too restrictive conditionalities.

- In order to avoid that the COVID-19 crisis turns also into a veritable EaP crisis European leaders must continue to take strong actions in favour of our neighbouring partners. In today’s situation, in which COVID-19 wreaks havoc in the Union’s fragile eastern and southern surroundings, and in which multilateralism is at a serious risk to further deteriorate exactly when it is most needed, hibernation is not an option for Europe’s external engagement efforts.

- The EU should engage with Africa and the neighbouring partner countries in developing sustainable action plans for economic recovery with a longer-term perspective. The forthcoming (online) EU EaP summit in June 2020 is a first opportunity for EU leaders to publicly confirm such aspirations. The high-level EU-African Union summit is scheduled for October this year with a chance for repetition.

- The EU has reacted quickly at the science front, but now it needs to secure its financial contribution to the European and Developing Countries Clinical Trials Partnership also under Horizon Europe, the successor programme to Horizon 2020. The EDCTP is the EU’s main platform for coordinating clinical development efforts with sub-Saharan Africa, financially supported under the current Horizon 2020 programme. Given the UK is the biggest country contributor for matching funds to the EDCTP[23], the latter could become more difficult after Brexit (which also bears implications for the UK’s status in Horizon 2020 and the forthcoming Horizon Europe).

- In order to make European science diplomacy sustainable, an improved consideration for international R&D cooperation in Horizon Europe is required, which must also be equipped with a correspondingly high budget.

[1] A countless number of articles has been published on the lack of a European solidarity, see one example here: https://www.euronews.com/2020/03/30/eu-project-in-danger-if-no-solidarity-on-coronavirus-crisis-says-economy-chief-gentiloni (accessed on 10 May 2020)

[2] At the end of February, the European Center for Disease Prevention and Control still spoke of a low to moderate risk of infection.

3] https://www.consilium.europa.eu/de/policies/covid-19-coronavirus-outbreak-and-the-eu-s-response/; (accessed on 4 May 2020). Information on the various funding sources can be found here: https://ec.europa.eu/info/funding-tenders/opportunities/portal/screen/covid-19 (accessed on 5 May 2020)

[4] https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/covid-firsteravscorona_actions.pdf; (accessed on 4 May 2020)

[5] https://www.imi.europa.eu/; (accessed on 4 May 2020)

[6] https://data.europa.eu/euodp/en/data/group/covid-19-coronavirus-epidemic; (accessed on 4 May 2020)

[7] https://www.euvsvirus.org/; (accessed on 4 May 2020)

[8] https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/research_and_innovation/research_by_area/documents/ec_rtd_cv-pledging-event_factsheet.pdf (accessed on 13 May 2020)

[9] http://www.rfi.fr/en/science-and-technology/20200504-billions-raised-as-world-pledges-to-bankroll-coronavirus-vaccine-effort-covid-19-who-wellcome-trust-bill-gates (accessed on 5 May 2020)

[10] https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_20_940; (accessed on 28 May 2020)

[11] https://www.bertelsmann-stiftung.de/en/our-projects/strategies-for-the-eu-neighbourhood/project-news/in-the-corona-crisis-who-is-the-more-reliable-international-partner (accessed on 30 April 2020)

[12] Romano Prodi, “A Wider Europe – A Proximity Policy as the key to stability”, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/SPEECH_02_619 (accessed on 30 April 2020)

[13] See Jayati Gosh from the Jawaharlal Nehru University New Dehli: https://www.dissentmagazine.org/online_articles/the-pandemic-and-the-global-economy (accessed on 11 May 2020)

[14] https://www.chathamhouse.org/file/what-could-economic-impact-covid-19-be-africa (accessed on 25 April 2020)

[15] https://eeas.europa.eu/headquarters/headquarters-homepage/77470/%E2%80%9Cteam-europe%E2%80%9D-global-eu-response-covid-19-supporting-partner-countries-and-fragile-populations_en (accessed on 25 April 2020)

[16] https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_20_604 (accessed on 25 April 2020)

[17] https://www.politico.eu/article/coronavirus-debt-relief-eu-africa/ (accessed on 29 April 2020)

[18] https://www.thenewhumanitarian.org/news/2020/04/23/Coronavirus-emergency-aid-funding (accessed on May 12 2020) N.B. The New Humanitarian uses data from the FTS – Financial Tracking Service of the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) which can be accessed here: https://fts.unocha.org/

[19] https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2020/04/17/pr20168-world-bank-group-and-imf-mobilize-partners-in-the-fight-against-covid-19-in-africa (accessed on 30 April 2020)

[20] https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2020/apr/15/first-thing-who-stops-funding-who-in-a-pandemic-donald-trump-thats-who (accessed on 30 April 2020)

[21] https://cepi.net/ (accessed on 30 April 2020)

[22] https://www.glopid-r.org/ (accessed on May 4 2020)

[23] Information taken from Science Business, 05 May 2020, https://sciencebusiness.net/international-news/covid-19-crisis-underlines-value-african-research-investment (accessed on 7 May 2020)

- European Council: COVID-19 coronavirus outbreak and the EU’s response https://www.consilium.europa.eu/de/policies/covid-19-coronavirus-outbreak-and-the-eu-s-response/

- European Commission (08.04.2020): Coronavirus: EU global response to fight the pandemic https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_20_604

- European Commission, European Research Area corona platform https://ec.europa.eu/info/funding-tenders/opportunities/portal/screen/covid-19

- European Commission, Coronavirus Global Response: EUR 1 billion mobilised under Horizon 2020 https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/research_and_innovation/research_by_area/documents/ec_rtd_cv-pledging-event_factsheet.pdf

- European Commission (27.05.2020): Europe’s moment: Repair and prepare for the next generation https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_20_940

- European Union External Action Service (11.04.2020): “Team Europe” – Global EU Response to Covid-19 supporting partner countries and fragile populations https://eeas.europa.eu/headquarters/headquarters-homepage/77470/%E2%80%9Cteam-europe%E2%80%9D-global-eu-response-covid-19-supporting-partner-countries-and-fragile-populations_en

- Gosh, Jayati, Dissent Magazine (20.04.2020): The Pandemic and the Global Economy https://www.dissentmagazine.org/online_articles/the-pandemic-and-the-global-economy

- Herszenhorn, David M., POLITICO (28.04.2020): EU leaders to discuss debt relief for Africa https://www.politico.eu/article/coronavirus-debt-relief-eu-africa/

- International Monetary Fund (17.04.2020): World Bank Group and IMF mobilize partners in the fight against COVID-19 in Africa https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2020/04/17/pr20168-world-bank-group-and-imf-mobilize-partners-in-the-fight-against-covid-19-in-africa

- Kelly, Eanna, Science Business (05.05.2020): COVID-19 crisis underlines value of African research investment https://sciencebusiness.net/international-news/covid-19-crisis-underlines-value-african-research-investment

- Kosmehl, Miriam, Bertelsmann-Stiftung (09.04.2020): In the corona crisis, who is the more reliable international partner? https://www.bertelsmann-stiftung.de/en/our-projects/strategies-for-the-eu-neighbourhood/project-news/in-the-corona-crisis-who-is-the-more-reliable-international-partner

- Koutsokosta, Efi, Gill, Joanna, EuroNews, (30.03.2020): EU project in danger if no solidarity on coronavirus crisis, says economy chief Gentiloni https://www.euronews.com/2020/03/30/eu-project-in-danger-if-no-solidarity-on-coronavirus-crisis-says-economy-chief-gentiloni

- Lopes, Carlos, Chatham House (09.04.2020): What Could the Economic Impact of COVID-19 be on Africa? https://www.chathamhouse.org/file/what-could-economic-impact-covid-19-be-africa

- Morrow, Amanda, Radio France Internationale (04.05.2020): Billions raised as world pledges to bankroll coronavirus vaccine effort http://www.rfi.fr/en/science-and-technology/20200504-billions-raised-as-world-pledges-to-bankroll-coronavirus-vaccine-effort-covid-19-who-wellcome-trust-bill-gates

- Parker, Ben, The New Humanitarian (23.04.2020): Coronavirus emergency aid funding https://www.thenewhumanitarian.org/news/2020/04/23/Coronavirus-emergency-aid-funding

- Prodi, Romano, President of the European Commission (06.12.2020): A Wider Europe – A Proximity Policy as the key to stability https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/SPEECH_02_619

- Walker, Tim, The Guardian (15.04.2020): First Thing: Who stops funding WHO in a pandemic? Donald Trump, that’s who https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2020/apr/15/first-thing-who-stops-funding-who-in-a-pandemic-donald-trump-thats-who

- Tommaso, Emiliani (April 2020): How Relevant? The EU’s ‘Geopolitical Commission’ and the Response to the Covid-19 Pandemic, College of Europe Policy Brief #4/2020

- GeoPoll Survey Report (17.03.2020): Coronavirus in Sub-Saharan Africa – How Africans in 12 nations are responding to the Covid-19 outbreak (accessible here: https://www.geopoll.com/blog/coronavirus-africa/)

ISSN 2305-2635

The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Austrian Society of European Politics or the organisation for which the authors are working.

Keywords

coronavirus, global narrative EU neighbourhood, EU foreign policy, EU research policy, Africa, Eastern Partnership

Citation

Brugner, P., Schuch, K. (2020). The EU’s global response to the COVID-19 crisis with a focus on the Eastern Neighbourhood and Africa. Vienna. ÖGfE Policy Brief, 13’2020