Policy Recommendations

- Assess the demographic challenge in a multi-stakeholder perspective and design policies that reflect political, economic and social complexity of the issue. Earlier policy solutions should be analysed critically and fairly.

- Strengthen the rule of law. Strong democratic institutions with entrenched rule of law and legal certainty positively impact investments and economic development which, in return, incentivise people to remain, those who left to return, and new ones to come. Designing policies aimed at increasing birth rates without tackling broader negative political and economic trends, in particular corruption, will not reverse demographic decline.

- Reflect on positive aspects of people’s mobility and on best practices elsewhere.

- Show positive examples of immigration in Croatia and successful stories of integration. Discuss challenges of integration both for the local population and immigrants. Deconstruct fear.

Abstract

Croatia has been steadily losing its population in the course of the last three decades. Demographic decline is partly a result of wartime human losses in the 1990s, but ever since it has been steered by a combination of factors including decreasing birth rates, increasing emigration, and limited immigration. Since Croatia joined the European Union in 2013, emigration of mostly young and educated hit new record highs. The government’s policy solutions have not reversed negative demographic trends. Is it time that Croatia designs a progressive and comprehensive immigration policy?

****************************

Demographic decline of Croatia: What is to be done?

2021 census results

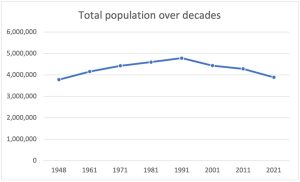

Croatia is a small country which over centuries has experienced waves of emigration. People left in search of better life for economic but also, at times, for political reasons. Not to dive deep into historical details, since the end of the Second World War, Croatia recorded the highest population at the time when it became an independent state. The 1991 census recorded Croatian population to be 4,784,265. Over subsequent years, this figure declined and in 30 years Croatia lost over 900,000 people.

The 2021 national census results show that Croatia has a population of 3,871,833 million people, 413,056 less than in 2011, a decline of 9.64%.[1] The main reason for the decline is intensified emigration since Croatia joined the European Union (EU) in 2013, although the negative demographic trend is recorded since 1991. The sharpest decline is recorded in eastern parts of Croatia, where in some locations reaches over 20%.

The main reason for the decline is intensified emigration since Croatia joined the European Union (EU) in 2013, although the negative demographic trend is recorded since 1991.

A percentage of children age 0-14 is slightly over 14%, while seniors over the age of 65 make 22.45% of the population. With declining birth rates, Croatian population will continue to age.

Source by the Croatian Bureau of Statistics, compiled by the author.

Both trends – low birth rates and emigration – have contributed to Croatia losing over 400,000 people in a decade. Some warn that the reality is actually bleaker and that considerably more persons are actually absent. Namely, many who left in recent years maintain their residence status and are officially counted as residents although in reality they no longer reside in Croatia.

Both trends – low birth rates and emigration – have contributed to Croatia losing over 400,000 people in a decade.

Croatian National Health Insurance’s published data as of 30 September 2022 shows the total number of insured persons in Croatia is 4,106,642.[2] If the total population of Croatia according to the 2021 census is subtracted from this figure, the result shows that in Croatia there are over 234,000 insured people than the total number of citizens.

These people, it is assumed, do not live in Croatia, but they continue to hold their insurance status and are registered in the country as unemployed. A new law on mandatory health insurance aims at clearing this gap. The official statistics may not reflect the real situation, but people have various explanations of how this is possible. A dentist in one Croatian town describes that she has 2,375 patients registered in her office, but many of them no longer live in Croatia. Yet, they come to see her from time to time, usually around holidays.[3]

Determining the exact number of voters is also confusing. Croatia has almost the same number of voters as citizens – 3,660,054 voters[4] and 3.871,833 citizens. What is surprising is that the number of voters is rising while the total population is declining.[5] This is not a new situation and for years media, independent analysts and non-governmental organisations have warned about manipulations of voter registrations.[6] Reasons are several – residence permits given to citizens of neighbouring Bosnia and Herzegovina in bordering regions with Croatia, a lack of efficient updates of voters’ lists that retain names of deceased, changing rules for registration of diaspora voters, and changing methodologies of counting ethnic minority voters. In some cases, in particular with residence given in Croatia to citizens of Bosnia and Herzegovina is believed to favour HDZ party (Hrvatska demokratska zajednica/Croatian Democratic Union) where in exchange for benefits received on the basis of residence status (social welfare, health access, etc.) they vote for HDZ. Marko Rakar is a data analyst who in 2009 revealed a story about phantom voters lists in Croatia for which he received a global e-democracy award by the French Parliament. According to Rakar, Croatia currently has around 500,000 voters more than citizens of 18 years and older. There is little political will to clean voters’ registration lists, partly because this mess favours right-wing parties, HDZ but also Most (Most nezavisnih lista/The Bridge), as well as Serb ethnic parties.[7]

Drivers of demographic decline

Some authors claim that with the existing negative fertility rate, Croatia is already at a point from which a natural demographic recovery seems to be very difficult to achieve.

Demographic decline since 2012 has been steady. A difference between newly born and deceased persons in 2012 was -2.3, while in 2021 it was -6.7 on 1,000 persons. A number of newly born children has decreased (41,771 in 2012 and 36,508 in 2021). The number of deceased remained around 50,000 between 2012 and 2020, but it sharply rose to 57,023 and 62,712 in 2020 and 2021 respectively, due also to the COVID-19 pandemic.[8] Some authors claim that with the existing negative fertility rate,[9] Croatia is already at a point from which a natural demographic recovery seems to be very difficult to achieve.[10]

A lack of economic development impacts negative demographic trends in two ways – by stimulating emigration and by domestic youth unemployment. In Croatia, unable to afford housing, many young people have no other option but to remain living with their parents and even start their own families in overcrowded households. Croatian youth (up to 29 years of age) still living with their parents hold EU record – 92% of male and 84% female. Many thus see no other option but to leave the country.[11]

A lack of economic development impacts negative demographic trends in two ways – by stimulating emigration and by domestic youth unemployment.

The entry into the EU allowed many Croatians to seek better paid jobs in more developed EU countries. Most people left for Germany, Austria and Ireland.[12] What is interesting is that the official statistics from these three countries and Croatia do not correspond. For example, taking the year 2016 for which the data for all three countries exist, the German statistics shows the immigration of 55,970 Croatian citizens while Croatian statistics show 20,432 citizens that have moved to Germany. What needs to be taken into account is that Germany records all citizens of Croatian nationality that have moved to Germany, although they may have come from a different country such as Bosnia and Herzegovina bearing Croatian citizenship. However, the difference is still significant between German and Croatian statistics.[13] The same situation is noticed with Austria and Ireland. While Austrian data show over 5,000 Croats who have moved to Austria in 2016, Croatian data display 533 emigrants. According to Irish data 5,312 Croatian citizens requested residence in Ireland in 2016, Croatian statistics record 1,917 emigrants to Ireland.[14] Tado Jurić, a migration scholar, gives even bleaker figures. According to his research, since Croatia joined the EU 310,000 people moved to Germany and 20,000 to Austria and Ireland respectively.[15]

Confusion about the exact number of people living abroad while retaining residence in Croatia may start to change. As of 2022 the state tax authority initiated a process of contacting such persons with a request to pay taxes for income received abroad, even if taxes in the country where the income was received are already paid.[16] This new regulation is met with an outcry, a trade union of migrant workers has been established. They claim that there are many irregularities regarding this new situation, there is no clear and transparent criteria why some people must pay taxes on their income abroad and others do not, why, for example, sailors are treated differently and those that work in EU institutions. The tax authority and the ministry of finance respond that the regulation is in line with EU laws and that claims that this is a witch hunt are unfounded.[17] The trade union warns that this regulation may become the motivator for the largest exodus of Croatians in recent history.[18]

The young and educated are leaving in higher numbers.

Why are people moving? For the majority this is job opportunity and overall economic prosperity. However, these reasons, when disaggregated and looked into more detail, show that over 60% of people who have left Croatia since 2013, when it joined the EU, had previous employment in Croatia.[19] A percentage of those who leave within the age group of 25 – 40 with university degrees is almost 39% which is 12% higher than the percentage of people in the same age group that remain in Croatia.[20] Thus, the young and educated are leaving in higher numbers.

Within the EU member states 40.3% young Romanians, 32.6% young Bulgarians, 30.8% young Slovenians and 26.1% young Croatians would be ready to leave their countries.

Croatia is not unique though. A study on youth in Southeast Europe shows that in Croatia young people have actually the least desire to leave. On top is Albania in which 66.6% young people expressed the wish to immigrate, followed by Kosovo, North Macedonia, Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina. Within the EU member states 40.3% young Romanians, 32.6% young Bulgarians, 30.8% young Slovenians and 26.1% young Croatians would be ready to leave their countries.[21] The reasons why young people leave being the following:

- Access to education,

- Employment outlooks,

- Disillusionment with politics,

- Anxiety about the future,

- Low levels of social trust.[22]

Similar reasons are listed in national studies in Croatia. A poll among high school students shows that 47.5%, and not surprisingly, those with best marks, see their future outside Croatia.[23]

As in other countries in Southeast Europe, emigration is stimulated by negative social and political situation. Legal uncertainty, state instability, high level of corruption, culture of impunity, nepotism and the focus on the past are elements that stimulate emigration, not only a lack of jobs.[24]

People want to go where their career success does not depend on personal connections, but on their knowledge and ability. They want their children to be raised in societies which value education and creativity, in societies that are open, tolerant, and inclusive.

As in other countries in Southeast Europe, emigration is stimulated by negative social and political situation.

Results of a survey conducted in 2021 by the World Youth Alliance in Croatia shows that around 50% of young people consider leaving Croatia. Among those who leave many do not vote leading to a conclusion that one of the reasons for leaving is apathy or a sense that nothing can be changed.[25] Corruption in particular is often given as one of key reasons for leaving the country. Even Dubravka Šuica from HDZ, a current European Commission vice-president for democracy and demography, agree that corruption is one of factors driving people out.[26] However, this is a clear example of a non-self-reflective statement by a veteran politician from a party that governed Croatia 22 out of 30 years since the country became independent, the only political party which has been sentenced by the Croatian supreme court for corruption, and whose former prime minister Ivo Sanader, as well as other ministers, are in jail or under investigation for corruption. Capacity for self-reflection would be a first sign of democratic responsibility, but this kind of political culture has not yet developed in Croatia.

Corruption in particular is often given as one of key reasons for leaving the country.

Solutions proposed by the government

In the course of the last few years, Croatia’s authorities have begun to treat demographic decline as an existential threat that impacts not only the country’s wellbeing and prosperity but also its national security. The current National Security Strategy lists demographic revitalisation among its nine strategic priorities.[27] In 2017, the government established a Demographic Revival Council as an inter-ministerial body whose task is to supervise and coordinate implementation of demographic measures.[28]

The current National Security Strategy lists demographic revitalisation among its nine strategic priorities.

The measures are primarily oriented towards financially supporting young families and new parents. Those offered in 2022 are, for example, financial support for newly born children, paid parent leave, subsidized kindergarten, school meals, healthcare and textbooks, more scholarships, support for housing, and others.[29] The government also tries to stimulate a return of Croatian diaspora. A government Office for Croats outside Croatia has established a welcome office which offers advice and support to those who express interest to return.[30] In 2021, Croatian government issued a new programme “I choose Croatia” to stimulate intra-state migration, and in particular, to attract Croatian citizens living in the European Economic Area countries to return to Croatia and start their business. The financial support to returnees is a maximum of HRK 200,000 (around €26,600) paid in the period of two years.[31] This programme is active as of the beginning of 2022 and, since a process of application and approval lasts several months, its effects are not yet visible. Until the end of May 2022, 17 persons returned to Croatia on the basis of this programme.[32]

The government also tries to stimulate a return of Croatian diaspora.

How to attract Croatian diaspora to return to its homeland has been a constant challenge for Croatian governments. Some scholars advocate this measure as the only viable remaining option, referring to how Ireland and Israel attract their diaspora.[33]

An active immigration policy, however, does not exist in Croatia, but one of the reasons for the lack of political will to design programmes to attract foreigner workforce may have been a result of relatively negative perceptions about foreign workers. A study on attitudes of the local population towards foreign workers reveal that 75.9% of Croats think that foreign workers should adjust to the values of the Croatian society; 59.3% think that if a foreign and a domestic worker possess same qualifications, a domestic worker should always have a priority; and 55.3% think that the government should not allow immigration of foreign workers.[34] There are no recent studies about perception of migrant workers in Croatia while the above figures date from a decade ago. What can be observed, however, is that Croatia has opened channels for labour immigration, in particular workers in tourism and construction. The figures are rapidly rising. While in 2021 Croatia issued around 80,000 work permits, this year it is expected to go over 100,000. On top of the list are workers from Bosnia and Herzegovina, followed by Serbia and, as of 2022, Nepal.[35] Lacking programmatic policy planning with respect to immigration, as in so many other policy areas, Croatia improvises and reacts to changing circumstances by providing short term solutions.

Lacking programmatic policy planning with respect to immigration, as in so many other policy areas, Croatia improvises and reacts to changing circumstances by providing short term solutions.

Effects of emigration could be mitigated by immigration, but Croatia cannot become attractive to high skilled workforce as long as its structural problems, such as politicised judiciary, high levels of corruption, limited investment in education and innovation, prevail. High skilled Croatians leave for these reasons, other high skilled workers will not come if these conditions persist. Even during the 2015/16 refugee crisis when nearly 700,000 people transited through Croatia, less than 0.02% of refugees applied for asylum.[36]

Local communities cannot wait for national-level solutions. In order to attract new residents, primarily from Croatia but also foreigners, municipalities are adopting measures to incentivise people to remain and new ones to settle. The Pašman municipality offers the most generous financial support for new-borns – €1,591 for the first, €3,182 for the second, €4,773 for the third, €7,955 for the fourth, and €13,258 for the fifth child. The Municipality of Vrbovsko for example offers €13,258 to young families as support for home purchase.[37] Municipalities are competing how to design the most attractive packages within their limited budgets.

Instilling the rule of law should be the government’s priority.

However, such measures are local and limited in scope. Low birth rates contribute to around 40% of demographic decline, while emigration drives the remaining 60%.[38] The government needs to self-critically assess causes for demographic decline. These are primarily economic but also social and political. Narrow demographic measures or measures intended to attract Croats to return will not resolve the problem. High skilled labour force will also avoid Croatia as long as overall socio-economic conditions do not improve. The rule of law is a cornerstone of a functional democracy, but also of a viable economy. Instilling the rule of law should be the government’s priority.

Conclusion

Croatia describes itself as a country of emigration. People emigrated for various reasons in the past – mostly economic but also political. During socialist Yugoslavia, its citizens could seek employment as Gastarbeiter in Western Europe. Since Croatia joined the EU, emigration accelerated and the country lost 10% of its population in a decade, combined with lower birth rates. Exact figures are hard to establish as the quality of statistical data to measure this overall loss of population is rather low.

Causes for low birth rates and emigration are connected. Young people without jobs, even if they stay in Croatia, delay forming families or having children because they cannot afford the cost of these new obligations. A solution for many is to leave.

Croatian government relies on conservative solutions to tackle demographic decline – stimulating fertility by offering various financial incentives to young families, modestly increasing annual work permits, and facilitating a return of diaspora. Yet, these solutions will not suffice to change the negative demographic trend. The government must take a pro-active approach and design a sustainable, comprehensive and forward-oriented immigration strategy.

Croatia, as a small state, sees demographic decline as an existential threat. However, basking in self-remorse and fear does not help. Policy solutions need to tackle the causes of emigration, not merely treat the symptoms. Confronting corruption and other structural problems will require unwavering commitment to the rule of law and democratic accountability, which is still lacking.

****************************

[1] “Objavljeni konačni rezultati Popisa 2021“, Croatian Bureau of Statistics, 22 September 2022. https://dzs.gov.hr/vijesti/objavljeni-konacni-rezultati-popisa-2021/1270.

[2] Croatian National Health Insurance, accessed 19 October 2022. https://hzzo.hr/hzzo-za-partnere/broj-osiguranih-osoba-hzzo.

[4] “Zaključen popis birača za lokalne izbore“, Ministry of Justice and Public Administration, 2021. https://mpu.gov.hr/zakljucen-popis-biraca-za-lokalne-izbore-25041/25041.

[5] Vladimir Matijanić, “Hrvatska je vrlo blizu danu kada će imati više birača nego stanovnika“, Indeks.hr, 14 January 2022. https://www.index.hr/vijesti/clanak/hrvatska-je-jako-blizu-danu-kad-ce-imati-vise-biraca-nego-stanovnika/2332446.aspx.

[6] Gabrijela Galić, “Provjerili smo kako je moguće da je Hrvatska u četiri godine dobila više od sto tisuća novih birača“, Faktograf, 31 July 2020. https://faktograf.hr/2020/07/31/provjerili-smo-kako-je-moguce-da-je-hrvatska-u-cetiri-godine-dobila-vise-od-sto-tisuca-novih-biraca/.

[7] “Rakar objasnio kako se vara na izborima: ‘Fantomski birači najčešće glasaju za HDZ, Most i SDSS’“, RTL.hr, 18 April 2022. https://www.rtl.hr/vijesti/hrvatska/rakar-objasnio-kako-se-vara-na-izborima-fantomski-biraci-najcesce-glasaju-za-hdz-most-i-sdss-cc7449da-c352-11ec-8250-52c0e7bbe268.

[8] “Prirodno kretanje stanovništva Republike Hrvatske u 2021“, Croatian Bureau of Statistics, 21 July 2022. https://podaci.dzs.hr/2022/hr/29028.

[9] 1.415 children per woman with a steady decline of approximately 0.5% annually since 2009. https://www.macrotrends.net/countries/HRV/croatia/fertility-rate.

[10] Monika Komušćanac, “Revitalizacijski modeli stanovništva Republike Hrvatske”, Doctoral Thesis, 2017.

[11] Lauren Simmonds, “Croatia Youth Leaving Country Because They Can’t Leave Parental Home?”, Total Croatian News. https://www.total-croatia-news.com/politics/59435-croatian-youth.

[12] Mia Burić, ”Republic of Croatia as a Source of Migrants and Demographic Aspects of National Security“, M.A. Thesis, Faculty of Political Science, University of Zagreb, 2022. (The thesis is in Croatian).

[14] Ibid., information for both countries on pp. 35 – 36.

[15] Ivica Nevešćanin, ”Tado Jurić: Korupcija je izravno povezana s odlaskom 370,000 Hrvata. Političarima na vlasti uvijek odgovara iseljavanje, kao i onima u Jugoslaviji!“, Zadarski.hr, 28 August 2021. https://zadarski.slobodnadalmacija.hr/zadar/4-kantuna/tado-juric-korupcija-je-izravno-povezana-s-odlaskom-370-000-hrvata-politicarima-na-vlasti-uvijek-odgovara-iseljavanje-kao-i-onima-u-jugoslaviji-1123133.

[16] Ivanka Toma, “Porezna kreće u ‘lov na gastarbajtere’, uskoro će slati opomene, a kazne su ogromne!“, Jutarnji.hr, 22 August 2022. https://www.jutarnji.hr/vijesti/hrvatska/porezna-uprava-krece-u-lov-na-gastabajtere-uskoro-ce-slati-opomene-a-kazne-su-ogromne-15237602.

[17] Marijan Brala, “Gastarbajteri dobili odgovor Porezne: ‘Ne idemo u lov, evo na koga se odnosi obveza prijave primitka’“, Jutarnji.hr, 24 August 2022. https://www.jutarnji.hr/vijesti/hrvatska/gastarbajteri-dobili-odgovor-porezne-ne-idemo-u-lov-evo-na-koga-se-odnosi-obveza-prijave-primitka-15238802.

[18] “Sindikat nakon najave kazni gastarbajterima: Čeka li nas najveći egzodus Hrvata u novijoj povijesti?“, Varaždinske vijesti, 23 August 2022. https://www.varazdinske-vijesti.hr/aktualno/sindikat-nakon-najave-porezne-slijedi-li-najveci-egzodus-hrvata-u-novijoj-povijesti-62090.

[19] Siniša Bogdanić, “Novi iseljenici iz Hrvatske: Odlaze oni koji već imaju posao“, Deutsche Welle, 18 December 2017. https://www.dw.com/hr/novi-iseljenici-iz-hrvatske-odlaze-oni-koji-već-imaju-posao/a-41829200.

[21] ”Five Points on Youth in Southeast Europe“, Friedrich Ebert Foundation, February 2018, p. 6. https://library.fes.de/pdf-files/bueros/sarajevo/14217.pdf.

[23] A study is referenced in the article by Zara Troskot, Marija Elena Prskalo, Ružica Šimić Banović, ”Ključne odrednice iseljavanja visokokvalificiranog stanovništva: slučaj Hrvatske s komparativnim osvrtom na nove članice EU-a“, Zbornik radova Pravnog fakulteta u Splitu, pp. 877 – 904, 2019.

[24] Drago Župarić-Iljić, ”Iseljavanje iz Republike Hrvatske nakon ulaska u Europsku uniju“, Friedrich Ebert Foundation, 2016. Zara Troskot, Marija Elena Prskalo and Ružica Šimić Banović, ”Ključne odrednice iseljavanja visokokvalificiranog stanovništva: slučaj Hrvatske s komparativnim osvrtom na nove članice EU-a“, Zbornik radova Pravnog fakulteta u Splitu, 877 – 904, 2019; Tado Jurić, ”Iseljavanje Hrvata u Njemačku. Gubimo li Hrvatsku?“, Školska knjiga, 2018.

[25] “Svjetski savez mladih Hrvatska: Mladima je potrebno omogućiti kvalitetne životne uvjete i sigurnost“, 9 February 2022. https://mimladi.hr/2022/02/09/svjetski-savez-mladih-hrvatska-mladima-je-potrebno-omoguciti-kvalitetne-zivotne-uvjete-i-sigurnost/.

[26] “Dubravka Šuica: Ljudi odlaze iz Hrvatske zbog korupcije“, Index.hr, 28 January 2022. https://www.index.hr/vijesti/clanak/dubravka-suica-o-demografskoj-katastrofi-mi-smo-clanica-eu-tek-osam-godina/2335687.aspx.

[27] ”Strategija nacionalne sigurnosti Republike Hrvatske“, 2017. https://narodne-novine.nn.hr/clanci/sluzbeni/2017_07_73_1772.html.

[28] ”Decision on establishment of a Council on Demographic Revitalization of the Republic of Croatia“, 2017. https://narodne-novine.nn.hr/clanci/sluzbeni/2020_12_141_2731.html.

[29] “Demographic measures on local and regional level“, https://demografijaimladi.gov.hr/obitelj-i-mladi-u-sredistu/demografija-5636/demografske-mjere-na-lokalnoj-i-zupanijskoj-razini-5671/5671?fbclid=IwAR0J8fuMUluHEySDWKsjKQ12ZFF2I1gcEQ16JFgvNuYQKRW3HP6a4ctqMO4.

[30] ”Welcome Office“, https://hrvatiizvanrh.gov.hr/korisne-informacije/ured-dobrodoslice/791.

[31] ”Mjera Biram Hrvatsku: Za povratak u Hrvatsku poticaji do 200,000 kuna“, Press Release, Croatian Government, 22 December 2021. https://vlada.gov.hr/vijesti/mjera-biram-hrvatsku-za-povratak-u-hrvatsku-poticaji-do-200-tisuca-kuna/33598.

[32] Jagoda Marić, “Preduga administracija ili jednostavno slab interes? Provjerili smo koliko je povratnika dosad iskoristilo mjeru ‘Biram Hrvatsku’“, Novi list, 30 May 2022. Preduga administracija ili jednostavno slab interes? Provjerili smo koliko je povratnika dosad iskoristilo mjeru “Biram Hrvatsku” – Novi list

[33] “Hrvatska se demografski neće izvući bez modela useljavanja“. Lecture by Stjepan Šterc. Večernji.hr, 27 September 2018. https://mojahrvatska.vecernji.hr/vijesti/hrvatska-se-demografski-nece-izvuci-bez-modela-useljavanja-1272540.

[34] Jadranka Čačić-Kumpes, Snježana Gregurović, and Josip Kumpes, ”Migracija, integracija i stavovi prema imigrantima u Hrvatskoj“, Revija za sociologiju 42(2012) 3:305-336, pp. 318-319.

[35] Gordana Grgas, “Rekordan broj stranih radnika: Ove godine premašit ćemo 100.000 izdanih dozvola za strance“, Jutarnji.hr, 20 May 2022. https://www.jutarnji.hr/vijesti/hrvatska/rekordan-broj-stranih-radnika-ove-godine-premasit-cemo-100-000-izdanih-dozvola-za-strance-15199816.

[36] Senada Šelo Šabić, Sonja Borić, ”At the Gate of Europe. A Report on Refugees on the Western Balkan Route“, Friedrich Ebert Foundation, 2016. https://www.irmo.hr/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/At-the-Gate-of-Europe_WEB.pdf. The percentage is calculated from figures on p. 12.

[37] Branimir Bradarić, “Kako se lokalne zajednice širom Hrvatske bore protiv bijele kuge”, Al Jazeera Balkans, 26 July 2021. https://balkans.aljazeera.net/amp/teme/2021/7/26/kako-se-lokalne-zajednice-sirom-hrvatske-bore-protiv-bijele-kuge?fbclid=IwAR1JFSePnH4xbR__ak2SUZc8rRAloXIGBNsQw8lft38bMi05TU_mUDxWccY.

[38] Vedran Salvia, “Psiholog: Ljudi odlaze zbog korupcije. Neće se vratiti zbog famoznih 200.000 kuna”, Index.hr, 15 January 2022. https://www.index.hr/vijesti/clanak/ima-nas-400000-manje-ljudi-bjeze-zbog-korupcije-i-siromastva-to-je-toksican-spoj/2332505.aspx.

About the article

ISSN 2305-2635

The views expressed in this publication are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Austrian Society of European Politics or the organisation for which the author is working.

Keywords

demography, migration, corruption, Croatia, European Union

Citation

Šelo Šabić, S. (2022). Demographic decline of Croatia: What is to be done? Vienna. ÖGfE Policy Brief, 21’2022