Policy Recommendations

- The first step in order to advance the Sustainable Development Goals in the Western Balkans is spurring transnational cooperation between the countries in the region. A set of common targets could harmonise the different legislations and involve more effectively the civil society.

- A transnational network of renewable energy should be seen as a security infrastructure, vital for the independence and autonomy of the whole region. Even if the investments in the field have been delayed by COVID-19 and the war in Ukraine, the Western Balkan countries should build cross-border interconnectors to create a coherent energy grid without holes and dead ends.

- In order to decrease the percentage of young people neither in employment nor in education and training and solve other social problems, the Western Balkan countries should smooth their mobility rules and agree on specific provisions for students and workers willing to spend time abroad.

Abstract

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are a new ambitious benchmark that the United Nations has adopted to scientifically assess the advancement made by single countries in sustainable growth. The European Union (EU) fully embraces these objectives and is recently anchoring to these international standards many of its plans on sustainability and development. Inevitably, the growing importance of the SDGs for the EU programming and the acquis communautaire has consequences on a wide set of EU policies, including enlargement and accession. Indeed, even though the Copenhagen criteria do not explicitly mention environmental goals, the political dialogue on the SDGs between Brussels and all the EU candidate countries today is vibrant but not much investigated. This Policy Brief aims to shed a light on the relationship between SDGs and the EU policy of enlargement, focusing its attention on the Western Balkan region. The research will analyse the state of the art of the SDGs in different Western Balkan nations on their path for accession, trying to underline differences and similarities, and inquiring whether the implementation of these goals has an impact over the ongoing political dialogue between Brussels and the region.

****************************

Bringing sustainability to the Western Balkan region

Introduction

In the last years, the United Nation Agenda 2030 has turned into one of the most important benchmarks to assess the path towards more prosperous and sustainable communities. The overarching aim of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) is to achieve 169 ambitious targets spanning over multiple sectors, from health and education, to eradicating hunger, ensuring access to water, sanitation, energy and fighting climate change. The SDG targets are not a mere collection of goals and wishful thinking. They reflect, for the first time, a global consensus on sustainable development, by also setting a framework to achieve decent living conditions for all. The SDGs include developed and developing countries alike, establishing the principle of a shared responsibility toward the current and future generations. The SDGs provide the research community and civil society organisations with valuable and measurable tools to call for action and encourage a step change in political leadership. Finally, the SDGs foster international cooperation as they require to rely on strong global partnerships and the involvement of multiple stakeholders. For some countries, the main international partner to deal with is the European Union (EU), an organisation pioneer in green transition that is gradually introducing sustainability assessments in its external action tools. Today, the parameters of sustainable development are not only accounted in different fields, such as trade agreements and agricultural policy, but also entangled with the criteria of accession for new member states. This Policy Brief addresses the triangle link between SDGs, Western Balkan countries and EU accession policy, providing an overview about the state of play and some policy recommendations.

The Western Balkans

The objective of this Policy Brief is twofold. First, it aims to discuss the role that sustainability has played in the accession process and negotiations between the EU and the countries in the Western Balkan region. Second, it focuses on the performance of the Western Balkan countries regarding the SDGs through a selection of five key socio-economic indicators to provide policy recommendations to both European and national decision-makers.

The premise is that – despite important political progress achieved so far – very few Western Balkan countries appear on track to achieve the SDGs, as demonstrated from the latest available reviews published by the High-Level Political Forum (2019 and 2020).[1][2] Indeed, the COVID-19 pandemic hit hard the path towards a sustainable transition not only in the region but worldwide, halting or in some cases even reversing the progress achieved by individual countries and the international community.[3] The least Developed Countries (LDCs), alongside the Landlocked Developing Countries (LLDCs), “Small Island Developing States” (SIDS), and countries in humanitarian or fragile situations borne the biggest burden of the crisis, as they suffered from weak health systems, limited social protection coverage, insufficient financial and other resources, vulnerability to external shocks, and dependence on international trade. Therefore, – and understandably – these same states experienced the worst setback even in sustainability, as the transition for many downgraded in importance to just a side priority in this cascade of emergencies. A recent report of the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP)[4] highlighted that the social and economic impacts of COVID-19 are set to widen the gap regarding the SDGs between countries at different stages of development. On the flip side, other reports however have shown that the developing countries would have the potential to increase their current pace and even exceed pre-COVID-19 development trajectories if they wanted through a combination of innovative policies, investments in green economy and digitalisation (the so called ‘SDGs Push’).[5] In the array of these developing countries committed to achieve the SDGs, the Western Balkans (WB) do occupy a peculiar place for their relationship with the EU. This region is deeply complex and faced with specific socio-economic and environmental challenges that need to be tackled as soon as possible not only for the sake of international stability but to ensure better standards of living for the local populations.

The impact of COVID-19 on the socio-economic balance of the Western Balkans

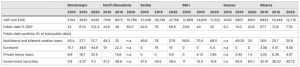

The pandemic has exposed the Western Balkan countries to several socio-economic vulnerabilities. COVID-19 has particularly put under strain public finances that were already struggling due to the consequences of the 2008-09 global financial crisis. A recent study highlights that the reduction of gross domestic product (GDP) due to COVID-19 has triggered an increase in public debt levels, exposing the health sector and social safety net programmes. Table 1 below provides an overview of the data on public debt, its share in GDP as well as the structure of the public debt portfolio of the countries in the region.

Table 1: Public debt portfolio of the Western Balkan 6 countries

Source: Lukšić et al. (2022)[6]

Not all the Western Balkan countries have been affected by the crisis in the same way. Countries highly dependent on services’ exports, such as Albania, Kosovo and Montenegro, have been more vulnerable to immediate shocks, especially in light of substantial losses in tourism during the summer seasons. All Western Balkan countries have though experienced strong effects of the pandemic on their labour markets, due to their specific features: high share of informal, temporary and self-employment, together with very weak social safety nets. Most of the countries have witnessed a further worsening of their labour market indicators, something that could exacerbate the already existing social and political tensions.

Not all the Western Balkan countries have been affected by the crisis in the same way.

Likewise, the limited room for fiscal manoeuvring is also hampering the path towards sustainable socio-economic development in the region and staving off the rigid EU accession criteria. These indicators, rooted in the Copenhagen criteria, demand a sound and solid public finance to successfully complete the candidacy procedure. More specifically, the economic criteria require to withstand competitive pressure inside the EU single market and thus secure the public finance from potential external liabilities. The resilience of the overall financial systems is gauged trough different indexes, including the accountability of the public spending, which should follow both a rule of rationality and efficiency.[7] In its Guidance for the Economic Reform Programmes 2022-2024,[8] the European Commission evaluated mainly these two aspects, addressing not only the public debt and deficit of each nation but the overall rationale behind the governments’ investments. The European Commission’s assessment mirrors a greater – but under control – tendency to rely on deficit financing in all the Western Balkan countries, and in some cases, like in Kosovo and North Macedonia, a questionable investment strategy.[9] In the current environment, public resources need to be coupled with private funds that would require a proper rule of law and economic environment to fully harness their potential. Some studies are suggesting using innovative finance mechanisms, such as environmental, social, governance/sustainability-linked bonds and debt-for-climate swap investments to accomplish this goal.[10] Countries such as Serbia have already started to use this kind of instrument, with Belgrade issuing its first ever green bond worth 1 billion USD in September 2021. The 7-year maturity and 1% annual coupon security settled is aimed at investments in rail and subway network, sewerage, water and wastewater processing, flood protection, biodiversity protection, pollution prevention and control, waste management, support for energy efficiency measures and installation of rooftop solar panels.[11] Other Western Balkan countries are likely to follow with similar measures.

Likewise, the limited room for fiscal manoeuvring is also hampering the path towards sustainable socio-economic development in the region and staving off the rigid EU accession criteria.

The role of sustainability in the EU accession process

As outlined in the 2021 Europe Sustainable Development Report,[12] in recent years the SDGs have also provided a useful framework for constructive dialogue and exchanges between the EU and candidate countries in the Western Balkans. On the one hand, as already stated, sustainable development has been increasingly at the heart of EU legislation and policies both inside the Union and abroad. On the other hand, the SDGs have funded regional initiatives in the region, such as South East Europe 2030 Strategy,[13] adopted through the South-East European Cooperation Process (SEECP) and implemented with the support of the Regional Cooperation Council (RCC). The synergy between the EU and the United Nations (UN) in the region is, therefore, pivotal to understand the latest socio-economic developments.

As outlined in the 2021 Europe Sustainable Development Report, in recent years the SDGs have also provided a useful framework for constructive dialogue and exchanges between the EU and candidate countries in the Western Balkans.

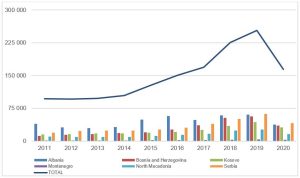

As the Western Balkans continue to bounce back from the social and economic impact of COVID-19, the 2021 EU-Western Balkans Summit[14] highlighted the need to unlock the potential of green and digital transition to accelerate the economic transformation of the region by creating new job opportunities and putting a halt to the dramatic levels of brain drain (see Figure 1).[15] For the purpose of this research, we will focus on five indicators reported by the European Commission which seem particularly important for the Western Balkan countries:[16]

- Poverty reduction (SDG1)

- Good health and wellbeing (SDG3)

- Energy intensity (SDG7)

- Young people neither in employment nor in education and training (SDG8)

- The frequency of internet use (SDG17)

Figure 1. Legal migration from the Western Balkan countries to the EU

Source: Eurostat (2022)

Comparative analysis of the socio-economic indicators

(1) Risk of socio-economic exclusion

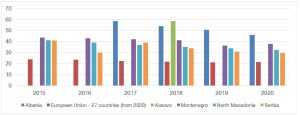

The latest data available display that all EU candidate and potential candidate countries experienced a reduction in the risk of poverty or social exclusion between 2015 and 2020.

All these social indicators, however not explicitly outlined in the Copenhagen criteria, are consistent with the EU social framework and all the guidelines that the member states abide to since the Lisbon European Council on economy and cohesion onward.[17] At the same time, all these priority areas are also embedded in the EU 2030 strategy on comprehensive development which was devised after the UN SDGs.[18] The appraisal of the single policy areas aforementioned is not easy, due to the changing situation in many Western Balkan countries and the evolving framework of reference. The first of the selected policy field reports the proportion of the population considered to be at risk of poverty or social exclusion. This indicator shows the sum of people that are either at-risk-of-poverty after social transfers, severely materially deprived or living in households with very low work intensity. The latest data available display that all EU candidate and potential candidate countries experienced a reduction in the risk of poverty or social exclusion between 2015 and 2020. The highest rate in 2018 was recorded in Kosovo (58.6%) but given that this is the only year available, it is not possible to truly assess this development over time. The countries that registered the best performance were Serbia (from 41% in 2015 to 29.8% in 2020), North Macedonia (from 41.2% in 2015 to 32.6% in 2020), Montenegro (from 43.8% in 2015 to 37.8% in 2020) and Albania (from 58.5% in 2017 to 46.2% in 2020). This means that the Western Balkans had an average risk of poverty indicator of 40.6% in 2019, therefore, double of the EU average of 20.9%, although by 3,9% less than in 2010.

Figure 2: Persons at risk of poverty or social exclusion, 2015-2020 (% of the total population)

Source: Eurostat (2022)

(2) Good health and wellbeing

Anyway, despite important fluctuations, all countries experienced a swift decline in the infant mortality rate between 2009 and 2020.

A second indicator widely used for SDG3 addresses child mortality, including ending preventable deaths of new-born children by 2030. As notorious, healthcare is a policy area that, according to the acquis communautaire, is mainly under the responsibility of the EU member states. However, the objective of a healthier Europe is consistent with the objective of European Health Union as outlined by President Ursula von der Leyen as she took over office.[19] Therefore, a better performance in this instance may draw these countries closer to Europe, as recognised by the European Investment Bank which has been investing on Western Balkan health care systems for years to help them to close the gap with the EU.[20] In the 2009-2019 period, the infant mortality rate in the EU candidate and potential candidate countries was higher than the one in the EU, but today there was a strong commitment from all countries to reduce neonatal mortality up to 12 per 1,000 live births or fewer. One best practice in this sense was Montenegro, which successfully more than halved the mortality rate in 2015, falling below the EU average and remaining below it until the end of the period. Anyway, despite important fluctuations, all countries experienced a swift decline in the infant mortality rate between 2009 and 2020. The strongest reduction was recorded in North Macedonia, where the rate of 5.7 deaths per 1,000 live births in 2020 was much lower than the 11.7 recorded in 2009. Albania followed a bizarre path, with a significant 3 points reduction registered until 2015 (from 10.3 deaths per 1,000 live births to 7.1), followed by a rapid increase until 2020 (with 10 deaths per 1,000 live births). Kosovo’s rate – for which data are missing for 2013, 2014 and 2020 – was fluctuating over time, in 2019 being 8.7, only somewhat lower that the 9.9 recorded ten years earlier. In this context, it ought to be mentioned that data for Bosnia and Herzegovina are only available for 2009 (6.5), 2010 (6.4) and 2012 (5.4). Overall, with the exclusion of Bosnia and Herzegovina, the average mortality rate of new-born children for the Western Balkans 6 (WB6) in 2019 was 6.8 deaths per 1,000 live births, compared to 3.4 registered for the EU members.

Figure 3: Infant mortality rate (number of deaths per 1,000 live births)

Source: Eurostat (2022)

(3) Clean and affordable energy

In this sector, the main bulk for the EU-WB cooperation is revolving around the Energy Community Treaty which sets several shared goals between the European Commission and the Energy Community Secretariat.

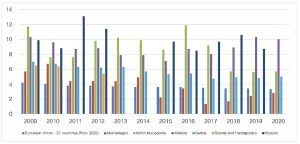

Another key area for assessing the progress towards SDGs concerns doubling the global rate of improvement in energy intensity. In this sector, the main bulk for the EU-WB cooperation is revolving around the Energy Community Treaty, which sets several shared goals between the European Commission and the Energy Community Secretariat. Together with others, Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, North Macedonia, Montenegro, Serbia and the EU are part of the Energy Community Treaty, an international organisation that envisages the creation of a common “energy acquis” between these countries and the EU.[21] Among the objectives of this cooperation, besides the establishment of a common market, there is an attention for a smart use of energy. The definition of energy efficiency is grounded on the gross inland consumption of energy in relation to constant price (or volume) the GDP; namely the energy supplied to the economy per unit of economic output. If the ratio between energy and GDP declines over time this indicates that less energy is required, thereby confirming that the economy concerned has made progress in relation to energy efficiency gains. Otherwise, the ratio worsened or remains stable, predicting a negative outlook. The figure below highlights that all Western Balkan countries have improved their energy efficiency from 2009 to 2020, with the strongest performance registered in Kosovo, North Macedonia and Serbia. Montenegro also showed some improvement, although data are missing for 2020. Lastly, Bosnia and Herzegovina has experienced worsening energy performance from 2014 to 2020, shifting from 446 to 466 kilogrammes of oil (equivalent per thousand EUR). Just for the sake of comparison, the energy intensity in the EU fell gradually from 2009 to 2020, reaching 116 kilogrammes of oil equivalent per thousand EUR of GDP in 2020. Therefore, despite the efficiency gains, the amount of energy required to produce a unit of GDP remained considerably higher in the candidate and potential candidate countries than in the EU: energy intensity ratios were generally 2 to 4 times as high as for the EU in 2020. This overall picture has been negatively assessed by the EU, not only because it parted ways with the SDGs but for its negative fallout on environment and employment.[22] According to the Regional Cooperation Council (RCC), the main forum for cooperation between South Eastern European countries,[23] and the afore quoted South East Europe Strategy, the goals expected to be met within 2020 included a dramatic increase of renewable energy, a significant investment in energy infrastructure and an empowerment of customers. The energy dimension was a pillar of the regional strategy for sustainable growth, linked with social policies and environment.[24] These reforms, if ever delivered, would have helped the Western Balkans to raise their standards and thus be more compliant with the EU/UN requirements and their own aspiration. As already explained, however, the non-fulfilment is likely to pose an obstacle for accession in a key sector that – more than others – is a crossover of different policies and priorities.

Figure 4: Energy intensity, 2014-2020 (kg of oil equivalent per thousand EUR)

Source: Eurostat (2022)

Defusing this complex situation and reconciling the current price increase, energy security and environmental protection are conceivable and feasible only through an even stronger and more coordinated action by the governments of the region and the EU.

The fundamental goal of moving towards clean and affordable energy was recently reaffirmed through the launch of a Green Agenda for the Western Balkans,[25] based on the EU Green Deal which the governments of the region have pledged to implement in order to contrast climate change and foster the ecological transition.[26] These tasks are made even more urgent today in light to Russia’s military aggression on Ukraine and ensued energy crisis. Although Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina and North Macedonia are largely dependent on Russia for natural gas (and Belgrade has even recently renewed its gas supply contracts with Moscow[27]), this only represents a small part of their energy mix. Rather, the crisis is affecting the region through rising prices for electricity imports and risks, on the one hand, to jeopardize the adequacy of domestic energy supply and, on the other hand, to aggravate their already precarious environmental situation. The high costs of electricity imports risks to push the WB countries to rely even more on the use of coal-fired power plants (from which today almost all countries derive a large part of their energy requirements). Defusing this complex situation and reconciling the current price increase, energy security and environmental protection are conceivable and feasible only through an even stronger and more coordinated action by the governments of the region and the EU. Promoting energy efficiency and accelerating the green transition will require, in the coming years, to move towards an even greater integration of energy networks and strengthen the coordination of integrated policies for all of South Eastern Europe.

(4) Young people neither in employment nor in education and training (NEETs)

Today, the importance dedicated to the NEET at a European level inevitably connects accession, UN goals and the European “acquis” in youth policies.

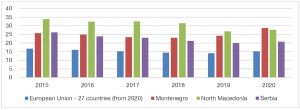

In order to measure progress on the SDG8 target, the EU collects data on the share of young persons (aged 15-24 years) who are neither in employment nor in education and training, referred to as the NEET rate. In the last decade, the European Commission settled the fight against this phenomenon as a priority, devising specific measures of contrast in concertation with non-governmental organisations and the civil society. In Europe 2020, the main tool deployed was the so-called Youth Guarantee, a financial instrument extended to the Western Balkans through the WB6 roadmap. The 4-steps strategy of the European Commission for the region encompassed different stages and recommendations for the recipients; they would embrace careers advice and job-search counselling, business start-up advice and mentoring, start-up grants and loans and education grants in partnership with financial institutions and European agencies.[28] The strategy for the next years will be following the conclusion of the 2021 Porto Summit and the provisions conveyed through the EU Action Plan of Social Rights.[29] The EU institutions are actively encouraging the candidate countries to fall in line behind its 2030 objectives, for instance through the allocation of (small and inadequate) incentives.[30] Today, the importance dedicated to the NEET at a European level inevitably connects accession, UN goals and the European “acquis” in youth policies. Even in this field, the assessment could be better.[31] Although data are missing for Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina and Kosovo, the strongest performer in the WB group as of 2022 is North Macedonia, where the NEET rate fell from 33.9 of 2015 to 27.6% in 2019. Montenegro and Serbia from 2015 to 2017 scored similar results but followed different trajectories afterwards: while both countries were close to a rate of 23% in 2017, in the years later Montenegro recorded a new increase to 28% in 2020 as against Serbia that showed a positive decrease to 20%. In any case, the NEET rate was substantially higher in all the candidate and potential candidate countries than in the EU, where it stood at 15%. Against that backdrop, some good news might come from the new wave of sensitivity on the issue that (at least) several countries of the region are starting to display.[32]

Figure 5: Young people neither in employment nor in education and training by sex, age and labour status (NEET rates) 2015-2020

Source: Eurostat (2022)

(5) Access to internet

The focus of the European Commission is on creating a Europe with harmonised rules for connectivity services, offering more choice to consumers and higher standard of service.

Regarding SDG17, the UN established the target “17.8.1”, which is gauged after the frequency of internet used by individuals aged between 16 and 74, and calculated for three different intensities: trimester usage, weekly usage and daily usage. In this regard, the European Commission is more than anything a provider of digital infrastructure and even its objectives – conveyed through its digital strategy – are related to the 5G and the facilities necessary to improve and expand the existing lines. The focus of the European Commission is on creating a Europe with harmonised rules for connectivity services, offering more choice to consumers and higher standard of service.[33] From their side, the Western Balkans seem ready to meet the UN goals, even despite an inadequate network of infrastructure. In 2020, all EU candidate and potential candidate countries presented high volumes with a daily use of the web shifting from 20% in 2009 to an impressive 71% in 2020. Kosovo reported the highest proportions of individuals aged between 16 and 74 using the internet in the last three months in 2020 (96%) and daily (93%). These figures are significant if we consider that in the EU, the trimester usage of the internet increased from 63% in 2009 to 88% in 2020 and that the daily use rose from 46% in 2009 to 80% in 2020.

Figure 6: Internet use individuals 2018-2020

Source: Eurostat (2022)

Conclusions

When faced with the challenge of the SDGs, the Western Balkan countries share similar environmental, economic and social constraints. The analysis of the five selected development goals shows that, notwithstanding minor differences, the attainment of the envisaged targets remains elusive. In order to meet the challenge in a more cooperative way, these countries together with the RCC should organise fair consultations around specific sets of goals. The societies of the Western Balkans are facing similar problems in healthcare, child mortality, youth access to the job market and economic exclusion. The response – as always – lies in a prompt reaction via transnational solidarity. The EU is suggesting a method – namely the transnational cooperation – that the member states itself are enforcing to respond to the new continental crises (COVID-19 first). A common effort from all the partners of the region could also help the international organisation and the EU itself to improve their statistical data collection and, therefore, upgrade the indicators used to evaluate accession. Another good side effect of this cooperation would be a major sharing of best practices among local authorities and municipalities, thereby realising a practical subsidiarity. Besides the quoted targets, there are several fields in which a better collaboration could be beneficial, such as the managing of transboundary environmental issues, the access and development of renewable energy sources, economic innovation and job creation. In all these sectors, a more efficient regional cooperation could trigger the benefits that often come with a scale economy (cost reduction, higher standard) and grow a shared knowledge. The SDGs could thus provide inspiration for a whole series of regional programmes that could contribute to develop economies, societies and above all build trust and create a sense of joint purpose.[34]

In particular, in order to advance the SDGs and spurring transnational cooperation between the countries in the region, the WB countries could undertake a number of urgent measures. Firstly, with the support of the RCC, they could set common targets in order to harmonise the different legislations and involve more effectively the civil society. Secondly, WB countries should invest in cross-border interconnectors to create a coherent energy grid without holes and dead ends. Finally, in order to decrease the percentage of NEET and solve other social problems, the WB countries should smooth their mobility rules and agree on specific provisions for students and workers willing to spend time abroad.

****************************

Photo: Gerd Altmann / Pixabay

****************************

[1] United Nations (2019), High-Level Political Forum on Sustainable Development. Available at: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/hlpf/2019#docs.

[2] United Nations (2020), Sustainable Development Goals Progress Chart 2020. Available at: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/26727SDG_Chart_2020.pdf.

[3] https://sdgintegration.undp.org/sites/default/files/Foundational_research_report.pdf.

[4] https://hdr.undp.org/content/human-development-report-2021-22.

[5] https://www.undp.org/publications/leaving-no-one-behind-impact-covid-19-sustainable-development-goals-sdgs#.

[6] https://energsustainsoc.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13705-022-00340-w/tables/2.

[7] In conformation with the acquis communautaire set out by the Treaty of Maastricht and detailed in the Council Recommendation 2015/1184 on “Broad guidelines for the economic policies of the Member States and of the European Union”.

[8] https://finance.gov.mk/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Guidance-for-the-ERPs-2022-2024-of-the-Western-Balkans-and-Turkey.pdf.

[9] European Commission, North Macedonia 2021 ERP assessment, Brussels, 20.4.2022 123 final, p.14; European Commission, Albania 2021 ERP assessment, Brussels, 27.4.2022, 126 final, p.8 (https://ec.europa.eu/neighbourhood-enlargement/enlargement-policy/policy-highlights/economic-governance_en).

[10] https://energsustainsoc.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13705-022-00340-w.

[11] Igor Todorović (2021), Serbia raises EUR 1 billion in its first green bond auction. Balkan Green Energy News, https://balkangreenenergynews.com/serbia-raises-eur-1-billion-in-its-first-green-bond-auction/.

[12] https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/meetings/international-summit/2021/10/06/.

[13] https://www.rcc.int/docs/581/south-east-europe-strategy-2030.

[14] https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/meetings/international-summit/2021/10/06/.

[15] https://www.friendsofeurope.org/events/eu-western-balkans-summit/.

[16] https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Enlargement_countries_-_indicators_for_Sustainable_Development_Goals#SDG_3_.E2.80.94_Good_health_and_well-being.

[17] European Union, Presidency Conclusion of the Lisbon European Council, 23 and 24 March 2000.

[18] European Commission, Sustainable Development: EU sets out its priorities, Strasbourg, 22 November 2016.

[19] https://europeanhealthunion.eu/. One of the pillars of this strategy is to line up the EU healthcare quality with the highest world standards and the international guidelines.

[20] https://www.eib.org/en/publications/eib-healthcare-investments-in-the-western-balkans.

[21] https://www.energy-community.org/.

[22] Martin Voß and Lutz Weischer, Supporting the Western Balkans’ Energy Transition: An Imperative Task for the German EU Council Presidency, German Watch, Berlin, 2020.

[23] https://www.rcc.int/pages/2/about-us.

[24] Regional Cooperation Council, South East Europe 2020, Bruxelles, 2013.

[25] European Commission, Guidelines for the Implementation of the Green Agenda for the Western Balkans, 6 October 2020, https://neighbourhood-enlargement.ec.europa.eu/guidelines-implementation-green-agenda-western-balkans_en.

[26] Regional Cooperation Council, Sofia Declaration on the Green Agenda for the Western Balkans, 10 novembre 2020, disponibile su www.rcc.int/docs/546/sofia-declaration-on-the-green-agenda-for-the-western-balkans-rn.

[27] https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/5/29/serbia-ignores-eu-sanctions-secures-gas-deal-with-putin.

[28] Regional Cooperation Council, Youth Guarantee in Western Balkans, 2020.

[29] European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions (Eurofund), Living and working in Europe, Bruxelles, 2021.

[30] https://ec.europa.eu/neighbourhood-enlargement/news/eu-boosts-youth-employment-western-balkans-eu10-million-small-and-medium-enterprises-2020-08-06_en.

[31] Please note: the following statistics the ratio is calculated as a rough share of all young residents in these countries, excluding only those whose attendance of the educational system remains unclear.

[32] https://www.divac.com/News/2906/National-Dialogue-for-Youth-Employment-launched.shtml.

[33] https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/connectivity.

About the article

ISSN 2305-2635

The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Austrian Society of European Politics or the organisation for which the authors are working.

Keywords

European Union, Western Balkans, COVID-19, sustainable development, Sustainable Development Goals, accession

Citation

Fattibene, D., Castiglioni, F., Bonomi, M. (2023). Bringing sustainability to the Western Balkan region. Vienna. ÖGfE Policy Brief, 05’2023