One year on, nothing is the way it used to be

Policy Recommendations

- Through the “Spitzendkandidaten” process for the nomination of the President of the Commission the politicisation of the EU Commission has increased. This design therefore needs to be retained for the European Elections in 2019, however, not at the cost of the core competences of the Commission.

- For the European Elections in 2019, Heads of State and Government have to consider at an earlier stage whom they are going to put forward as their candidate. Only by these means a stronger party political content-politicization of the election campaigns and a strengthening of the European parties will be achieved.

- The European Parliament has to be further strengthened. However, the power to decide on the appointment of leaders fully on their own shall not be foreseen, because there should be no full parliamentarisation of EU-politics in a Union, which is not only one of its citizens, but also one of its states.

Abstract

November, 1st saw the first anniversary of Jean Claude Juncker and his team taking over their duties in the “last chance” European Commission – as they named it themselves. A perfect day to reflect, whether the Commission is living up to its promises and in how far the “Spitzenkandidaten” process is influencing policy making in Brussels – also to provide recommendations for the optimisation of the European Elections in 2019.

****************************

The Juncker Commission has Brussels in a state of upheaval

One year on, nothing is the way it used to be

365 days after Jean-Claude Juncker was elected President of the European Commission, Brussels is in a state of upheaval. Under Juncker’s leadership, the European Commission has become tangibly more political. On the one hand, this can be seen from the composition of the College of Commissioners. Never before have there been so many Commissioners with top political careers, nor has there ever been such an influential First Vice President. Furthermore, Juncker himself acts as a politician, proving that there is a link between the voting in European elections and the election of the Commission’s President.[1] This is exemplified by Juncker’s “ten priorities” for his five-year term of office, the “€315-billion Juncker investment plan” that is intended to benefit the crisis-stricken countries in southern Europe or the “17-point plan” prepared for the EU Balkan summit.

On the other hand, the ‘Spitzenkandidaten’ or ‘lead candidates’ system creates a new accountability on the part of the Commission’s President towards the people of Europe. Only time will tell, however, whether the new, more political Commission has come closer to Europe’s citizens. That is indeed the aim of REFIT, the Commission’s Regulatory Fitness and Performance programme, or might the Commission be tempted, in the wake of the Better Regulation agenda, to shift the decision-making process away from the legislative towards the executive? And what about the use of the European Citizens’ Initiative? Though initially celebrated as a great opportunity that would help to unify Europe, euphoria has since waned. Since 2012, only three of the 51 initiatives have been successful (Right2Water, One of Us and Stop Vivisection), partly because the bureaucratic obstacles are still too great.

Closer cooperation between the Commission and European Parliament

Besides major restructuring within the Commission, the main effect of Juncker’s appointment has been to increase cooperation between the Parliament and the Commission to a significant extent. Juncker’s Commission draws its legitimacy from the European Parliament, and the Parliament sees the Commission as its Commission. Thus, when it comes to major political issues, the Commission is far more likely than it was in the past to reflect the Parliament’s attitude. For example, it made a courageous proposal for a fairer division of the refugees, against the will of the member states. Likewise, in the crisis in Greece, it has been prepared to make more concessions to the Greek government, thus unequivocally taking the Parliament’s line on both issues. The Juncker Commission is acting as an extended arm of the Parliament here.

The Juncker Commission as an extended arm of the European Parliament

Besides the effects it has in terms of content, the concept of Spitzenkandidaten also affects the balance of power between the Commission and the European Parliament. The Parliament has succeeded in gaining the loyalty of the Juncker Commission through the Spitzenkandidaten process. A new distribution of voting powers in the European Parliament[2] has led to strengthened inter-institutional convergence between the Parliament and the Commission that did not previously exist in this form. This can be seen, for example, in the fact that the Commission has a greater interest in terms of its own political power in always keeping the major political groups informed, in particular, through the Commissioners from that group of parties, in order to avoid problems with the Parliament at a later stage.

The Parliament has succeeded in gaining the loyalty of the Juncker Commission through the Spitzenkandidaten process.

Hence, the outcome of the Spitzenkandidaten process has certainly also led to a further increase in the role of the Parliament in the European Union.[3] However, an EU that is not only a union of citizens, but also a union of states, cannot and should not aim to create a fully fledged role for the Parliament in European Union politics. There is just as little provision in the process of allocating the top positions for the idea that the Parliament should have the sole power of decision-making as there is in EU legislation itself – not just in the highly degressive proportionality of its composition, but also bearing in mind the respective voter turnouts and consequently the greater legitimacy of the European Council.

New areas of activity for the European Parliament

Since REFIT means that the Juncker Commission has come up with significantly less draft legislation, there is an opportunity in the coming years for the European Parliament to bring the EU closer to its citizens. Besides many initiatives of its own, it has already begun to open up new areas of activity for itself, which will ultimately benefit citizens. On the one hand, this has to do with an increased interest in how EU law is implemented in the member states and the question of the extent to which European laws create the desired effect at national, regional or local level (Bolkestein Directive).[4] On the other hand, this means dealing with technical regulations in the form of delegated acts and committee procedures. With nearly 2000 binding legal acts per year, they have a great influence on the functioning of the Single Market and thus on citizens as well (for example, energy or water efficiency). The Parliament will have more time to devote itself to these regulatory technical standards and to monitor them.

New distribution of voting power in the European Parliament

In the new European Parliament, as before, decision-making is dominated by the two large political groups, the EPP and the social-democratic S&D, even though the two groups have been on an equal footing since last year. At the same time, however, there has been a redistribution of voting power: both the centre-left and centre-right coalition options have fallen victim to power politics. The former does not have a majority, and the political differences have grown too large for the latter: the EPP is increasingly resistant to cooperating with the European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR), because anti-European parties such as the Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) and the Danish People’s Party are represented within it. The grand coalition of the EPP (Weber) and S&D (Schulz and Pitella) is more significant than ever.

The changes are mainly making themselves felt inside the respective political groups. Since majorities are slender, the national delegations within the two largest political groups have gained a particular role. This has been shown by the latest votes on the TTIP, the progress report on Turkey, the European strategy for secure energy or the mandate for the UN Climate Conference in Paris in 2015.

The ones who are currently benefiting from this development the most are the German delegations. They benefit because they belong to one of the largest national delegations. Above all, they tend to present a very united front, giving them great political power. For example, if the 34 CDU and CSU delegates were to collectively defy the EPP whip, this would put the absolute majority of the EPP and S&D at risk.

Since this is not in the political groups’ interest, discipline within the political groups effected through procedural changes has been the subject of intensified efforts since the beginning of the eighth legislative period.[5] Positions as coordinators or rapporteurs, for example, will be henceforth only given to active delegates who toe the party line.[6] This is a familiar phenomenon in national parliaments, but not previously in the European Parliament. This also explains why an increased number of delegates have not turned up to the most recent votes. They are avoiding the whip.

In the first year, the left and right-wing populist delegates have not succeeded in transforming their election success into political capital.

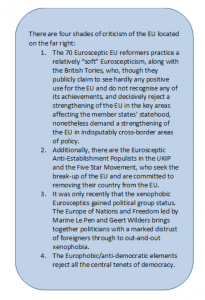

Furthermore, in the first year, the left and right-wing populist delegates have not succeeded either in transforming their election success into political capital. Whereas Eurosceptic parties in the seventh legislative period made up hardly 20 per cent of delegates, they are now 30 per cent.[7]

Despite their victory across Europe, they have not been able to cash in on this victory in the form of political power. Above all, this is because they do not present a united front. This applies to the AfD, but also to the Front National under Marine Le Pen and Geert Wilders’ PVV, for example, which only cast a unified vote 60 percent of the time. The figures for UKIP and the Five Star Movement are as low as 29 per cent. The internal coherence of the largest political groups, however, is around 90 per cent.[8]

Gaining seats is not necessarily the same thing as winning voting power. All in all, the pro-European groups have continued to prevail substantially in votes in the new Parliament as well. The liberal ALDE, for example, is now only the fourth largest political group, but it wins votes most often, almost 90 per cent of the time.[9] Political groups that are critical of Europe such as the GUE-NGL or EFDD, however, lag far behind.[10] As long as the internal coherence of the parties that are critical of the EU does not increase, their increased numbers of delegates will not be transformed into a greater political influence and the work of the Juncker Commission will not be endangered.

Recommendations for the optimisation of the Spitzenkandidaten process in the 2019 European elections

It is an obvious point to make: a connection between the votes cast and the election of the President of the Commission will only continue to exist if the nomination of lead candidates – in its 2014 form – is retained in 2019. Thus everything depends on how successful Juncker’s Commission presidency becomes. If his work bears fruit, the Spitzenkandidaten process will also be considered a success and the initial interpretation of Article 17(7) of the Treaty on European Union will be upheld. Subsequently, this will benefit a more markedly party-political focus during election campaigns, since the European party groups will base their campaigns on the genuine relevance of their lead candidates.

Thus the Spitzenkandidaten system would lead to a strengthening of the European parties (Europarties), since the significance of the nomination processes would increase.

Thus the Spitzenkandidaten system would lead to a strengthening of the European parties (Europarties), since the significance of the nomination processes would increase.[11] At the same time, greater interdependence with the manifesto process is to be expected. Consequently, the debate between the parties could be experienced at European level, which in turn would not be without consequences for European integration. Besides, the lead candidates, who had no discernible influence on the manifesto process in 2014, might contribute to the development of the European manifesto, to avoid presenting a collection of all the national manifestos or at least to avoid competing with them.

What is more, however, institutional and political changes would be necessary to prevent the European elections from remaining a kind of by-election.[12]

Only a single European electoral law would be able to remove the representation biases in European elections due to 28 different national European election laws.

Only a single European electoral law would be able to remove the representation biases in European elections due to 28 different national European election laws. Studies have also shown, however, that the visibility of the lead candidates in most countries was already higher than that of the European delegates during the seventh legislative period. Politically speaking, though, a further personalisation of EU politics – coupled with a party-political polarisation of content – would surely be desirable. Only then, after all, would national quality newspapers cover the lead candidates in detail when reporting on the election campaigns (even though they would probably always only focus on the candidates for the two largest political groups).

Furthermore, the use of television debates across Europe needs to be reconsidered.[13] The crucial question at the 2019 European elections will be whether the organisational difficulties and language barriers can be overcome, and whether simpler rules for the television debate format can be implemented.

Closing remarks

The current refugee crisis has shown that the European Union is only as strong as the solidarity of its members. This means that even the leaders of the various political groups will have to consider at an earlier stage whom they are going to put forward in the 2019 European elections. When Juncker was elected lead candidate of the EPP – a move that some heads of government surely later regretted – there were probably only a few people who were aware of the gravity of their decision. However the dilemma remains: it is an unwritten rule that the President of the Commission is selected from among the former or current heads of government. There is hardly a head of government in office who would risk embarking on a European election campaign, since losing the election would probably mean having to resign at home as well. So are the only people left the former heads of government, such as Juncker himself in 2014? This would considerably reduce the pool of candidates.

Moreover, the European Union needs a narrative that presents the EU as part of the solution (and not as the cause of the crises). In this way, the debate between the parties will be experienced at European level and the citizens of the EU can regain their trust in the political viability of the European Union in the future. This is the only way in which the steadily growing scepticism towards Europe in its various forms and shades can be successfully countered.

[1] Schmitt, Hermann, Sara Hobolt and Sebastian Popa: Does personalization increase turnout? Spitzenkandidaten in the 2014 European Parliament elections. European Union Politics. Online verfügbar unter DOI: 10.1177/1465116515584626

[2] Kaeding, Michael und Niko Switek (2015) Europawahl 2014. Spitzenkandidaten, Protestparteien und Nichtwähler, Wiesbaden: Springer VS, 17-32.

[3] Vgl. Sara B. Hobolt (2014) A vote for the President? The role of Spitzenkandidaten in the 2014 European Parliament elections, Journal of European Public Policy, 21:10, 1528-1540, DOI: 10.1080/13501763.2014.941148

[4] http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=URISERV:l33237&from=DE

[5] Across the board, the aim for the coming year is to completely rework the European Parliament’s rules of procedure.

[6] Hurka, S., Kaeding, M., and Obholzer, L. (2015) Learning on the Job? EU Enlargement and the Assignment of (Shadow) Rapporteurships in the European Parliament. Gender, Work And Organization, 53: 1230–1247. doi: 10.1111/jcms.12270

[7] Oliver Treib (2014) The voter says no, but nobody listens: causes and consequences of the Eurosceptic vote in the 2014 European elections, Journal of European Public Policy, 21:10, 1541-1554, DOI: 10.1080/13501763.2014.941534;

[8] http://www.votewatch.eu/blog/what-prospects-for-the-new-far-right-ep-group/

[9] http://www.votewatch.eu/blog/alde-back-in-its-kingmaker-seat-in-the-ep/

[10] Sebastian Hurka (2015) “Zäsur oder ´business as usual´? Die Verteilung der Abstimmungsmacht im neu gewählten Europäischen Parlament“ , in M. Kaeding und N. Switek (Hrsg.) Die Europawahl 2014. Spitzenkandidaten, Protestparteien, Nichtwähler, Wiesbaden: Springer VS, 323-334.

[11] Switek, Niko (2015) “Viel Arbeit für Nichts? Die Programmprozesse der Parteien auf europäischer Ebene“, in M. Kaeding und N. Switek (Hrsg.) Die Europawahl 2014. Spitzenkandidaten, Protestparteien, Nichtwähler, Wiesbaden: Springer VS, 115-124.

[12] The 2014 European elections once again had all the characteristics of a by-election: in all 28 countries, the level of participation was lower than in the previous national poll. In 20 countries, there were partly landslide losses for the ruling parties, and in 25 countries small and new parties were often able to increase their share of the vote considerably.

[13] Dinter, Jan und Kristina Weissenbach (2015) “Alles Neu! Das Experiment TV-Debatte im Europawahlkampf 2014“, in in M. Kaeding und N. Switek (Hrsg.) Die Europawahl 2014. Spitzenkandidaten, Protestparteien, Nichtwähler, Wiesbaden: Springer VS, 233-246.

ISSN 2305-2635

The views expressed in this publication are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Austrian Society of European Politics or the organisation for which the author works.

Citation

Kaeding, M. (2015). The Juncker Commission has Brussels in a state of upheaval: One year on, nothing is the way it used to be. Vienna. ÖGfE Policy Brief, 35a’2015

Note

This Policy Brief has also been published in German.