Policy Recommendations

- Identifying and managing the main obstacles to return.

- Ensuring better interconnectedness between the ‘diaspora’ and the policies of return migration in order to facilitate return and re-integration.

- Developing a comprehensive package of measures dealing both with decisions to emigrate and return.

- Better implementation of the national policies and strategies in the field of migration.

Abstract

The last census in Bulgaria shows that population has shrunk by 11.5% in a decade. Low birth rate, high death rate and migration are the key factors behind the country’s demographic decline. Governmental strategy documents admit that Bulgaria has lapsed into a serious demographic crisis and recognise migration and especially return migration as one possible solution. However, the recognition of potential benefits from this phenomenon failed to translate into active and concrete policies aimed at attracting returnee´s involvement in the prosperity of the country.

Return migration gathered new momentum during the COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic has accounted for the return of many Bulgarians. These events have reconfirmed the need for a thorough re-evaluation of current policies concerning return migration and this accounts for the critical analysis of the Bulgarian case made in the following Policy Brief in order to identify possible vectors for improvement.

****************************

Return Migration in Bulgaria: A Policy Context of Missed Opportunities

Introduction

Many territories in Europe are experiencing population decline. This is a result of a combination of low fertility and emigration and is especially true for nearly all countries in the Western Balkans. For their most part these countries, Bulgaria being one of the examples, share a view on emigration in terms of a “national catastrophe” regarding a perceived loss of demographic and intellectual capital. Presumably, emigration countries would readily make an investment in policies devised to attract back the people they have “lost”. Moreover, return migrants could have a positive impact on the development of sender countries. There is extensive evidence showing that return migrants can have a beneficial social impact on their countries of origin as they bring in productive skills, technological knowledge, international networks and professional experience needed at the domestic labour market (Clemens et al., 2014; Le, 2008; Rapoport, 2004). It is also evident that examples of success can relate to well-elaborated policies affecting all relevant aspects of that field: from motivation for return to facilitation of the reintegration process.

Bulgarian governments identify return migration as a priority of their migration policy. Attracting Bulgarian nationals living abroad has been identified as a key policy objective in several National Migration Strategies (Zareva, 2018). The paradox in the Bulgarian case is that this prioritisation was not followed by steps toward dynamising the return process and facilitating the capitalisation of its benefits.

Return migration gathered new momentum during the COVID-19 pandemic. This is true not only for Bulgaria, but for most countries in Central and Eastern Europe, where the pandemic has accounted for the return of many nationals to their countries of origin back from receiver migration destinations. These events have reconfirmed the need for a thorough re-evaluation of current policies concerning return migration and this accounts for the critical analysis of the Bulgarian case made in the following Policy Brief in order to identify possible vectors for improvement.

From emigration to return migration – does such a tendency even exist?

The population of Bulgaria, which amounted to 6,838,937 persons in 2021, continues to decline. Emigration phenomenon is one of the factors determining this trend. The total number of Bulgarian nationals living abroad, by various estimates, vacillates between a little over 1 million and nearly 2 million and a half. Most of the Bulgarian emigrant population stays in the European Union (EU). Turkey is another major destination country for Bulgarians. Other countries of destination for Bulgarians are primarily the USA, Canada and Israel. Bulgarian emigration includes two categories:

- Bulgarian citizens residing temporarily or permanently abroad:

- Contemporary (“young”) Bulgarian emigration;

- “Old” Bulgarian emigration.

- “Historical” Bulgarian communities abroad and persons of Bulgarian origin and with Bulgarian national identity and possessing foreign or dual (foreign and Bulgarian) citizenship.

The total number of Bulgarian nationals living abroad, by various estimates, vacillates between a little over 1 million and nearly 2 million and a half.

What is important to this analysis is that the predominant attitude towards emigration is dominated by traumatic images inherited from communism, mostly associated with the “non-returnees” and “The Great Excursion” (Staykova, E., Otova, I., 2021), and from the dramatic descriptions of modern emigration associated with “brain drain” and “loss of the flower of the nation”. There is very little talk about the eventual positive aspects of the situation and what are the possible benefits for Bulgaria accruing from communities living outside the national territory. The emphasis is actually laid exclusively on the relation between the country’s demographic crisis and emigration. This phenomenon is often identified as one of the important factors for the deterioration of the demographic situation in the country, and the return of the new emigration to the country is seen as one of the responses to the demographic crisis. Attracting people of Bulgarian origin from the historical diaspora for permanent settlement in the country is seen in a likewise manner (Ivanova, V., 2015). This requires concrete government mechanisms, which underlines the need for a comprehensive and critical review of national strategies in that field.

The emphasis is actually laid exclusively on the relation between the country’s demographic crisis and emigration.

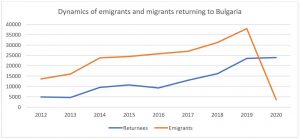

Concerning the dynamics of emigration, it is worth noting that although after 1989 there were estimates of the number of people who have left the country varying between 600,000 and over 1 million, in subsequent decades there has been a significant decrease in the number of departures. The average net annual rate of migration, which added up to 66,000 departures in late 1980s, has dropped to about 27,000 people in the 1990s and to 17,000 people between 2001 and 2011 (Angelov, G., Lessenski, M., 2017). Eurostat data indicates that between 2013 and 2019 the number of Bulgarians leaving the country has registered a gradual increase, with the number doubling over a five-year period – from 16,000 in 2013 to 31,000 in 2018 (Eurostat, 2020). It is noteworthy that 2020 has seen an unprecedented decline in the numbers of people leaving the country – from over 37,000 for 2019 to a little over 3,600 for 2020. Actually, this is the first time that those who have left were less in numbers than migrants arriving to the country.

Source: The author according to data from the National Institute of Statistics, 2022

Data from the National Statistical Institute (NSI) indicate that the last decade has seen a steady increase in the number of people returning to the country. Although research has reported a positive tendency, it should be taken into account that, except for the 2020 reversal, which is likely induced by the pandemic, return migration has proceeded on a considerably lesser scale than emigration. It is interesting to mention that it is easier to link return migration to the presence of crises rather than to the enforcement of government policies of attraction. This is confirmed by the dynamics surrounding the financial crisis in Europe, the Brexit, and is currently being confirmed in the context of the pandemic, with a more pronounced increase in the returnee flows (Georgiev, O., 2020). At this stage, it is still difficult to deduce accurate data as a great part of the returnees have not registered the change in their permanent address and are not included in the NSI statistics. In addition, no thorough investigation of the intentions of this group of returnees has been conducted so far.

Data from the National Statistical Institute (NSI) indicate that the last decade has seen a steady increase in the number of people returning to the country.

The context of policies – paradoxes and perspectives

Countries usually avoid to implement self-contained comprehensive return policies; these are rather incorporated as an element into other policies. Most often these policies are part of the general migration or integration policies, or are incorporated as a specific accent into the diaspora-oriented policies (Frelak, J. S., Hahn-Schaur, K., 2019).

In the Bulgarian case, the return policies belong to the overall policy on migration. In order to reduce the negative effects of emigration, public authorities have been developing policies aimed in principle at reducing emigrant flows and stimulating the return of Bulgarian population to the country. The main purpose is to improve the demographic balance, to increase the labour supply and the national human capital (Bogdanov G., Rangelova, R., 2012).

Bulgarian migration policy is characterised by its late inclusion into the political agenda which began with the accession of the country to the EU. However, it is well to keep in mind that even prior to these developments, it had certain elements which indicated accents and commitments. From the perspective of the present analysis, it is important to note the institutionalisation of the Agency for Expatriate Bulgarians as early as 1992. From that moment until now there have been a number of measures implemented in the field, and four national strategies have been developed, recognising the attraction of expatriate Bulgarians as a key emphasis in their priorities.

Bulgarian migration policy is characterised by its late inclusion into the political agenda which began with the accession of the country to the EU.

The first strategy (2008 – 2015) adhered to pronounced ethnically marked characterisation, prioritising the return of foreigners of Bulgarian origin, or the so-called Bulgarian historical diaspora. The second one (2011 – 2020) is in more general vein as regards the projected results – encouraging the return to Bulgarian labour market of Bulgarian nationals working abroad, and so is the third one (2015 – 2020) – providing for the attraction of Bulgarian emigrants back to Bulgaria in view of their final return. From the logic of the main strategic documents, one can conclude that they were intended to address mainly national and ethnic ideals rather than identifiable needs of the labour market (Ivanova, V., 2015). The most recent (currently effective) National Strategy of Migration of the Republic of Bulgaria (2021 – 2025) in regard to the Bulgarian migrant communities, among the priorities of the national policy are those aimed at their eventual return:

- Preparation of programmes (or actualisation of available ones) providing assistance for Bulgarian citizens intending to return or have already returned to the Republic of Bulgaria. These programmes are supposed to be aimed at the utilisation of the potential of Bulgarian citizens – as regards acquired knowledge, expertise, language skills, contacts, culture of communication, etc. and to facilitate them to the maximum extent in their establishment into the country upon their return.

- Conducting purpose-driven campaigns and intensive discussions, including at the political level, by involving the effort of the wide public in encouraging the return of Bulgarian citizens and settling into the Republic of Bulgaria (NSMRB, 2021).

It is important to note that from the perspective of Bulgarian policies, return is perceived mostly as a definitive act. This tendency, however, does not correspond neither to global migration dynamics, nor to empirical observations, which indicate that the dynamic migration model dominates much more frequently (Bobeva, D., Zlatinov, D., Marinov, E., 2019). The return can be an element in the complex, individual biography of mobility (Frelak, J. S., Hahn-Schaur, K., 2019). Both return migration as well as immigration in Bulgaria are much more related with the trends of ‘circular migration’. Paradoxically, even circular migration persisted in all strategic documents it was not a priority of Bulgaria’s migration policy. In most cases, ‘circular migration’ is referred to as an EU term that is derived from EU migration policy to which Bulgaria adheres to as part of its national strategy on migration (Vankova, Z., 2020).

One of the key elements in Bulgaria’s policy of attracting Bulgarian nationals residing abroad is the granting of Bulgarian citizenship based on origin. With regard to this policy there is discrepancy between expectations and achieved effect. The hypothesis that “new” Bulgarian citizens of Bulgarian origin would fit easier in society and without the need for specific assistance, does not always conform to reality. It turns out that these citizens such as the other immigrants also need support for their successful integration, and besides, it has become clear that a very small part of them in reality remain in the country. In most of the cases, Bulgarian citizenship is used for the purposes of further migration toward other states, most often in the EU.

One of the key elements in Bulgaria’s policy of attracting Bulgarian nationals residing abroad is the granting of Bulgarian citizenship based on origin.

Theory and practice demonstrate that good policies of return can be divided into: 1) policies aimed at attracting repatreates; 2) policies aimed at facilitating return, by way of targeting potential returnees (e.g. through information); and 3) policies seeking to ensure reintegration. Cited measures can overlap in the majority of cases. For example, migrants may require informational support prior to and following their return. Entrepreneurial support may attract emigrants to return, but it may also play an important role in the reintegration process (Frelak, J. S., Hahn-Schaur, K., 2019). Analysis of Bulgarian policies in the field of return has made it possible to outline one of their substantial deficits – lack of implementation. They have remained, just like many other public policies, mostly within the realm of strategy and limited to the level of the campaigns for attracting returnees. Primary initiatives in this field relate to encouragement of return migration through online information portals, consultation services and annual career forums to provide information to expatriate Bulgarians about opportunities to be found in Bulgaria (Zareva, I., 2018). Very few concrete steps have been undertaken to facilitate this return and almost none to support reintegration.

Analysis of Bulgarian policies in the field of return has made it possible to outline one of their substantial deficits – lack of implementation.

Conclusion

Bulgaria has been a country of emigration since the 1990s. The most popular view on emigration relates to the “brain drain” discourse and its negative effect on the country’s demographic dynamics, such as depopulation and ageing (Misheva, M., 2021). Governmental strategy documents admit that Bulgaria has lapsed into a serious demographic crisis and return migration could be one possible solution. However, the recognition of potential benefits from this phenomenon failed to translate into active and concrete policies aimed at attracting returnee´s involvement in the prosperity of the country.

****************************

Photo: #MigrationEU – A graffiti illustrating the eighth priority of the Juncker Commission “Migration”

Photographer: Johanna Leguerre

Artist: Thomas Dechoux

© European Union, 2015

Source: EC – Audiovisual Service

****************************

Angelov, G., Lessenski, M. (2017). Migration Trends in Bulgaria. Open Society Institute.

Bobeva, D., Zlatinov, D., Marinov, E. (2019). Economic Aspects of Migration Processes in Bulgaria. Economics Studies, 28(5).

Bogdanov, G., Rangelova, R. (2012). Final Country report for Bulgaria “Social Impact of Emigration and Rural-Urban Migration in Central and Eastern Europe”, Bulgaria, April 2012. On behalf of the European Commission DG Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion, coordinated by GVG institute in Cologne (Germany).

Frelak, J. S., Hahn-Schaur, K. (2019). Return Migration Policies in the Context of Intra-EU Mobility. Policy Brief. Vienna: ICMPD.

Ivanova, V. (2015). Return policies and (r)emigration of Bulgarians in the pre- and post-accession period. Social Policy Issues, 31, 119-136.

Krasteva, A. (2014). From Migration to Mobility: Policies and Roads. Sofia: New Bulgarian University.

Misheva, M. (2021). Return Migration and Institutional Change: The Case of Bulgaria.

National Statistical Institute (2022). External migration. Retrieved February 8, 2022, from: https://infostat.nsi.bg/infostat/pages/reports/result.jsf?x_2=120

Vankova, Z. (2020). National Approaches to Circular Migration in Bulgaria and Poland. In: Circular Migration and the Rights of Migrant Workers in Central and Eastern Europe. IMISCOE Research Series. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-52689-4_5

Zareva, I. (2018). Policies for Encouraging the Return of Bulgarian Migrants to Bulgaria. Economics Studies, 27(2).

About the article

ISSN 2305-2635

The views expressed in this publication are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Austrian Society of European Politics or the organisation for which the author is working.

Keywords

population dicline, emigration, return migration, migration policy, Bulgaria, COVID-19

Citation

Staykova, E. (2022). Return Migration in Bulgaria: A Policy Context of Missed Opportunities. Vienna. ÖGfE Policy Brief, 17’2022